You’re in China now, sir, where time and life have no value.

Style over substance, that’s a term that’s often levelled at some movies as a form of criticism; however, it doesn’t always have to be taken as such. On occasion, the humdrum, the trite and the unoriginal can be elevated by the presence of stylised techniques and images. Shanghai Express (1932) is a film where this is certainly the case – the story is pure, overblown melodrama but, in the hands of Josef von Sternberg, it manages to transcend the limitations of its plot and approach art.

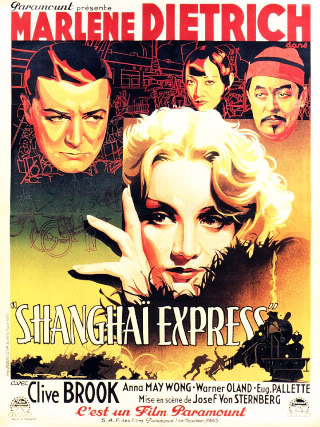

Events take place during the Chinese Civil War, with a rag-tag assortment of characters boarding the titular train. The main topic of conversation is the presence of a notorious prostitute called Shanghai Lily (Marlene Dietrich) who has been involved in a series of scandals up and down the Chinese coast. The reactions tend to vary from the outraged disapproval of a missionary to the more pragmatic acceptance by an American gambler and a disgraced French soldier. All the passengers know Shanghai Lily only by reputation, all but one that is. Captain Harvey (Clive Brook) is a British army surgeon travelling to Shanghai to perform an operation on a high ranking government official. Harvey and the woman were once lovers until an indiscretion on her part drove a wedge between them. From then on she embarked on a series of affairs and liaisons that earned her that colourful name. The rub is that these two people are still in love, but their pride and past histories prevent them from bridging the gap of mistrust that has grown up between them. The simmering sexual tensions are brought to a head when one of the passengers, a Eurasian by the name of Chang (Warner Oland), reveals himself as a Maoist rebel and hijacks the train. Chang’s aim is simply to hold the passengers, Harvey in particular, hostage until the government agrees to release one of his close lieutenants. In the end, it comes down to whether or not Shanghai Lily will sacrifice her new found honour to save the man she loves – and whether or not he will understand her motives. As I said, this is melodrama of the ripest and tawdriest variety. The whole thing works, and works very well, due to von Sternberg’s skill in evoking an atmosphere of decadence and exoticism that is dreamlike in its allure. The train itself is one of those inter-war extravagances that contrasts with the ramshackle station where the hostages are held. There are a number of notable sequences, but the one that made the greatest impression on me was the night-time assault on the train by Chang’s rebels. Bathed in expressionistic shadows and hissing steam, the rebels swarm over the stalled locomotive and dispose of the government troops. Those not killed immediately are rounded up and, as a heavy machine gun filmed in silhouette chatters into life, butchered on the platform. The camera angles and movements in this scene, and throughout the whole movie, are much more inventive and fluid than one normally expects in early sound pictures.

While von Sternberg clearly revelled in the theatrical oriental atmosphere, more than anything the film was an ode to Dietrich. It’s the way that Von Sternberg and cinematographer Lee Garmes lit and shot Dietrich that gives the film its power. He never misses an opportunity to zoom in on her, and Garmes’ setups are designed to accentuate that famous bone structure as the camera lingers. Her performance is nothing special in itself, but she oozes that languid, provocative sexuality that was her trademark. The dialogue that she (and all the cast members for that matter) is handed is delivered in a slow, deliberate, almost stilted fashion that actually works within the dreamy and unreal world that von Sternberg weaves. The role of Captain Harvey went to Clive Brook, and that damn near derails (sic) the whole show. He gives one of the most wooden and po-faced performances it’s been my misfortune to witness – although it could be argued, generously, that this actually serves to emphasise the priggishness of his character. Still and all, it’s hard to see how Dietrich’s character could possibly have carried a torch for this stuffed shirt for five years. The support cast led by Warner Oland and Anna May Wong are thankfully much better and help paper over the deficiencies of the leading man. Oland in particular does fine work as the charming but embittered Eurasian who compensates for his resentment of his mixed blood by indulging in torture and cruelty.

Shanghai Express was released a couple of years back in a 6-disc Dietrich boxset in the UK, although it’s since been made available individually. Universal have presented the film well considering its age, there are speckles and such, and some moments of softness, but it generally looks very good. Detail is quite strong at times and contrast is always good, the latter being especially important for a movie like this. The disc itself is completely barebones, which is a little disappointing but at least it can be bought for next to nothing. For a pre-code film it does seem a little coy in not coming right out and stating exactly how Shanghai Lily earns her keep, but it doesn’t exactly hide the fact either. Although the story is not going to blow anyone away, the intoxicating atmosphere is a real visual treat. Also, considering the weakness of the leading man, it’s a testament to the abilities of Dietrich, Garmes and von Sternberg that the end product is so good. I give it a big thumbs up.

The part I always remember is when she is in her cabin and the camera focuses on her face while she is smoking. I always thought the lighting and framing of it was outstanding.

LikeLike

Yes, the film is full of wonderful visuals. The story itself is nothing special but von Sternberg and Garmes make everything, including Dietrich, look amazing.

LikeLike

Pingback: Thunder in the East | Riding the High Country

Had this on a vhs back in the day. This was about the same time I really started to notice just how important lighting and such were able to enhance mood and the like. Nice pick, Colin

LikeLike

I think anyone who’s into noir will get a kick out of this – you can see how the style was developing even when it wasn’t a term that anyone was thinking about yet.

LikeLike

Pingback: Man with the Gun | Riding the High Country