I know what I am talking about when I am talking about the revolutions. The people who read the books go to the people who can’t read the books, the poor people, and say, “We have to have a change.” So, the poor people make the change, ah? And then, the people who read the books, they all sit around the big polished tables, and they talk and talk and talk and eat and eat and eat, eh? But what has happened to the poor people? They’re dead! That’s your revolution.

For someone who has dedicated so much time to writing about westerns, I’ll have to admit I have thus far neglected one of the best known directors of the genre: Sergio Leone. The truth is that, outside of Leone’s work, I cannot claim to be a huge fan of the spaghetti western sub-genre. So, while I have reservations about the Euro western in general, I have no hesitation at all acknowledging the artistry and sensibility of Leone. He didn’t actually make a large number of westerns, but those which he did have been highly influential. Once Upon a Time in the West has probably come to be accepted as his crowning achievement. While I have no intention of challenging that assertion, I do believe that A Fistful of Dynamite (1971) runs it a very close second in terms of emotional and intellectual depth.

The setting is Mexico during the revolution, and this provides the ideal background for Leone to lay out his thoughts. It affords him the opportunity to make points of both a political and personal nature, and weave them together into a critique of the direction of contemporary filmmaking. If Ford and Peckinpah had helped deconstruct the myth of the west, and paved the way for the emergence of the spaghetti western, then Leone (critically lauded as a cinematic revolutionary) set about the deconstruction of the myth of revolution itself. The film opens with Mao’s quotation describing revolution as being essentially an act of violence, and the events that unfold on the screen back up this assertion. Yet Leone, in his depiction of the frequent and mindless violence, never glories in the bloodshed. The film we see is a tragedy, a very human one, but at the same time it’s a celebration of friendship and kinship. We follow the fortunes of two men, John Mallory (James Coburn) and Juan Miranda (Rod Steiger) as they navigate the danger and treachery of a country in upheaval. John is an IRA man, an explosives expert on the run from his native land plying his trade in the silver mines. Juan is a bandit, a simple peasant content to live off whatever pickings come his way. A chance meeting draws these two contrasting characters together and binds their fates inextricably. Initially, each man views the other as a kind of dupe, a tool to be made use of to further their individual ends. Juan sees the Irishman as the means by which he can finally crack the famed bank in Mesa Verde, while John regards the Mexican as someone he can trick into serving the revolutionary cause. The first half of the movie takes us through the twists and turns of his mismatched duo’s effort to stay one step ahead of the other. The tone is light, bordering on the comedic at times, but the clouds are gathering in the background. The aftermath of the Mesa Verde escapade ushers in the second, darker part of the story. It’s here that the full import of the political situation starts to become clear. Where the violence of the earlier section had a cartoonish quality, the deaths that follow (and there are many) are cruel, and they have consequences. The romance of revolution is laid bare before us, both in words (see the opening quotation above) and actions, and it’s not a pretty spectacle. Leone’s controversial assessment seems to be that betrayal and loss – of family, friends and ideals – are both the result and foundation of revolution. That’s a brave and daring position to adopt at any time, and even more so in 1971 following hot on the heels of the previous decade’s climate of political, cultural and social change.

For the most part, A Fistful of Dynamite follows a traditional, linear narrative structure. However, there are teasing flashbacks interspersed throughout, each one adding to and expanding on those that precede it. These flashbacks relate to John’s past life in Ireland, and show Leone’s gift for inventiveness by gradually revealing the character. In fact, they work on two levels: (i) they act as an homage to Ford, by evoking the Irish preoccupation with betrayal as seen in The Informer and (ii) they delineate the background of John, simultaneously marking him out as a western hero in the classical mold. Leone was greatly influenced by Ford – a section in Christopher Frayling’s first class Once Upon a Time in Italy reprints a 1983 interview Leone gave an Italian newspaper, where he details his reverence for Ford and tells how he had a framed photo the latter had signed and inscribed in his honour occupy pride of place on his wall. In purely narrative terms, the flashbacks not only flesh out the character of John but they help explain why and how he came to this place in his life. John is essentially an enigmatic character, a man whose motivations are hard to divine, yet the brief interludes in Ireland allow us to build up a near complete picture of him by the end. By charting his descent from romantic idealist to disillusioned technician, the flashbacks both fill in the gaps and establish his western credentials. At first glance, an Irish bomber involved in the Mexican revolution might not appear to be a traditional western figure, but an examination of his character arc – betrayal, revenge, guilt and the quest for spiritual redemption – tells the tale. This lone figure, this outsider with a heart full of regret, searching for a way to bury his past is a recurrent one in the classic western. As such, John moves from apparent cypher to an incredibly complex man, a walking tragedy who seems destined to enter a new cycle of guilt and remorse – his involvement of Juan in his schemes brings only misfortune, and the matter of betrayal once again rears its head. The explosive finale, therefore, represents the only possible way for him to achieve a form of closure and inner peace. Coburn really got under the skin of John, maybe not quite reaching the levels of self-disgust he managed when playing Pat Garrett for Peckinpah but not far off either. The climactic scene on the engine plate with the traitor Villega (Romolo Valli), where he vows never to pass judgement on another man again, is a masterclass in bitterness and loathing.

By contrast, Juan is a much more straightforward character, a simple man with simple dreams. However, he too has to suffer at the hands of idealism. He’s well aware of the hypocrisies and false promises held out by the revolutionaries, yet he allows himself to be drawn ever deeper into the machinations of John and Villega. His casual vulgarity and lack of sophistication mark him as a semi-comedic everyman, someone whose attachment to family allows the audience to sympathize with him despite his being a common criminal. By having the audience view proceedings mainly from Juan’s perspective, Leone manages to hammer home the abrupt shift in tone at the halfway point much more effectively. The fate of his extended family, a direct consequence of his greedy foolishness and unwitting embroilment in politics, hits both him and us hard. The scene in the cave, with a bewildered and grief-stricken Juan stumbling around amid the carnage, is extremely moving no matter how often it’s seen. It brings both the film and the character to a new level, and neither one is ever the same again. Juan is transformed form a gregarious rogue with grandiose plans first to an image of despair, and then to something harder and colder. As an actor, Rod Steiger generally had a tendency to overcook it, to chew up the scenery before moving on to the props for afters. That is certainly in evidence in the early stages, where he is essentially a caricature of a Mexican bandit. However, he was capable of greater subtlety when the occasion demanded, and his reaction to the discovery in the cave, and all that follows, bears testimony to that. Steiger managed to tap into the development of his character, the journey he has taken, but still hold onto a touch of the innocence that makes him endearing. The final fadeout, with Juan’s moon face staring dumbly into the camera lens as his question is heard and the answer flashes before us, underlines Leone’s feelings and highlights the pitiful quandary faced by all of us.

Of course it would be impossible to discuss any Sergio Leone film without also referring to the music of Ennio Morricone. To any film fan, the names of the director and composer are inseparable, and the two men seemed to draw the best from each other. Morricone’s scores are always distinctive, primal pieces that complement the harsh landscapes and off-center characters in Leone’s films. For A Fistful of Dynamite, Morricone created music that was quite unlike the work he did on the previous Leone collaborations. There’s a light, jaunty quality to the scoring in the early scenes that matches the initial buffoonery of Juan and the ribbing of John. This gives way to the lush romanticism of the pastoral flashbacks and the ethereal vocals repeating the name Sean over and over. And finally, the more somber variation on that theme as the flashbacks grow darker and knowledge of what John did to his friend (Sean?) becomes apparent. One of the features on the DVD actually raises that question – who is Sean, and why does John call himself that at first? Of course, Sean is often used in Ireland as the Gaelic form of John, but Leone’s cutting of that scene and the use of the music therein does suggest some kind of transference is taking place, that John’s guilt is subconsciously driving him to adopt the name of his friend.

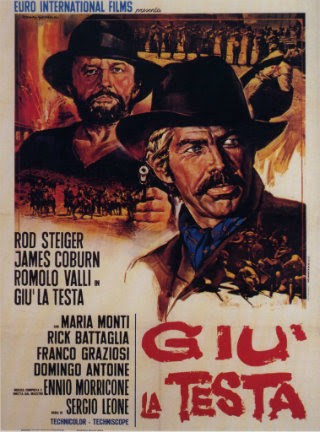

And finally, a word on the title. This movie has been known under a number of titles: Giù La Testa, Duck, You Sucker!, Once Upon a Time in the Revolution and A Fistful of Dynamite. The original Italian title arguably captures Leone’s message most succinctly – a plea to keep a low profile and thus avoid unwanted political attention and trouble – but the translation into English loses much of that and actually suggests some light-hearted romp. The other two alternatives both represent attempts to draw connections to and capitalize on Leone’s previous successes, but neither is really satisfactory either. In the end, I opted to use A Fistful of Dynamite to head the piece here mainly because that’s the one I’m most familiar with, and it’s also emblazoned across the cover of my DVD.

A Fistful of Dynamite is a movie that has been released in different forms over the years, but the 2-disc DVD from MGM presents the definitive cut. It restores the full, extended flashback at the end of the film and the title of Duck, You Sucker as it fades out. That full flashback, with its dreamy feel, is vital in fully understanding the relationship between John and his friend back in Ireland, and adds a different twist, a shade more ambiguity, to his actions. I’d hate to be without it. The edition is stacked with fascinating extras, not the least of which is an excellent commentary track from Sir Christopher Frayling. I have no particular complaints about the anamorphic scope transfer but I still feel it’s a pity it has yet to be released on Blu-ray. Among Leone’s films, this title sits alongside Once Upon a Time in the West in my affections, and might just edge it out. Objectively, it may not be the better film, but it has a kind of romanticism, and disillusionment – and what’s disillusionment but wounded romanticism anyway – that stirs something in my Irish blood. I don’t know, it’s a film I love – that’s as much as I can say.

I have a DVD under the DUCK YOU SUCKER title, which is how I saw it in the theater on it’s origianl release.

LikeLike

Randy, the US DVD uses the original release title on the cover – I guess that’s the one you have.

I have the UK special edition from MGM that uses A Fistful of Dynamite, although the US title does appear for the end credits on the film itself.

LikeLike

I have always loved “A Fistful Of Dymamite” since I first saw it in the late 70s. As an avid soundtrack collector, with a particular interest in Italian film music, it was also one of the first soundtrack LPs I bought. You’ve discussed it very well Colin and overall, I agree with what you have to say. Not with everything though. I suppose that the Special Edition DVD is the best version overall but I wouldn’t call it ‘definitive’. Recently, I re-bought the older MGM UK release of the film (which I had foolishly sold upon acquiring the Spec.Ed version.) because it presents quite a few different aspects. The differences between the various versions are many and too complicated to get into here but there were much more obscenities used in the older MGM release (as in the 90s laserdisc). I am not a film watcher who revels in the use of obscenities for their own sake but, here, they did add a certain punch to some scenes. Don’t worry Colin, I won’t lower the tone of your blog by quoting specific examples! 🙂

This business about Sean’s name, I’m not so sure about. I remember the documentary where it’s posited as a theory but I always felt that “Sean Mallory” is the Coburn character’s real name and that his use of ‘John’ is just another sign of his distancing himself from his previous life in Ireland.

I wouldn’t call myself a huge fan of Italian westerns but I do like many of them…and not just Leone. Tessari, Sollima and Corbuci have all produced some fine work too. However, I do keep the spaghettis in a separate compartment to American westerns in my head. They seem to exist in a parallel western universe and, provided I approach them in that way, I often enjoy them.

As regards the film’s title, there was another Leone documentary (I forget which) where Peter Bogdanovich, who worked with Leone briefly during the film’s early preparation stages…and who is, of course, a superb mimic, gave a hilarious account of their discussion on the “Duck You Sucker!” title. It seems that Leone was strangely convinced that ‘Duck You Sucker!’ was a well-known American slang expression which was in common usage in the U.S. Despite all attempts by Bogdanovich to convince him otherwise, Leone wouldn’t change it. Bogdanovich’s telling of the story was very funny!

One of the quotes from the screenplay I always remember is when Mallory tells Villega.. “When I started using dynamite I believed in many things….finally, I believed only in dynamite.”

LikeLike

Hi Dafydd. I used to have that old DVD as well, and either sold it or gave it away – can’t remember now. I suppose I should have kept it to have the different versions, but I think it can still be found if you look around.

I’m not 100% sure on the name business myself – the Sean/John business is, I think, left deliberately ambiguous. Being Irish myself, and being familiar with the interchangeable nature of the two names, I didn’t give it a lot of thought on first viewing. However, once I heard the theory that Sean might really be the friend, and then noticing the way Leone cut that scene, well I thought it was possible – maybe.

And I recall that anecdote about Leone being convinced that “Duck, You Sucker” was common parlance and therefore determined to use it.

LikeLike

That’s really interesting about versions Dafydd – I’ve got the Laserdisc too but otherwise only have the 2-disc edition that MGM put out about 6 years ago – I hadn’t picked up on the language differences – thanks for that info (even if it is really frustrating). One thing though, surely Coburn’s character is definitively identified on screen as ‘John H. Mallory’ in the newspaper clipping early in he film. Based on that I always felt that Mallory is thinking of his friend Sean on the soundtrack, haunted by the betrayal and sense that his life really ended with his friend’s – but is in a way the slight ambiguity suggests a melding of the two together in his mind, his guilt slowly but surely taking him towards death to meet his old friend/rival

LikeLike

Coburn is most certainly identified as “John Mallory” in the clipping that Juan finds among his belongings. As I said, my initial reaction to Coburn briefly calling himself Sean before correcting himself was that he was just using the Irish variant of the name. Dafydd’s idea that his dropping it signified a desire to distance himself from the past is plausible in that sense. However, the fact that he’s haunted by that past, and knows deep down that he can’t really escape it, returning repeatedly via flashback, draws me away from that interpretation.

LikeLike

It is fascinating how it’s not something that really seems an issue the first time you see it (or at least wasn’t for me) but once it has been pointed out, and you see how subtly Coburn plays the scene when he seemingly gets the name wrong. and the emphasis that is given to the whole business of his name, that is just adds this wonderful extra shading.

LikeLike

Absolutely; the more familiar you become with the movie, the more you notice it. My last viewing, just a few days ago, really brought home to me the artistry involved – the understated playing of Coburn and the expert way Leone shot and cut the scene.

LikeLike

Like yourself, Colin, I love westerns yet I’m not a big fan of this subgenre. However, besides Once Upon a Time in the West (and perhaps three other Euro-westerns NOT directed by Sergio Leone, though I do like For A Few Dollars More a lot), I am fond of this film. Excellent review.

LikeLike

Thanks David. I have tried hard to get into spaghetti westerns, and own a considerable number but, like Dafydd said, I see them as almost a separate species – the look and feel is totally different to the classic US variety. I do think Leone comes much closer to that classic form though, especially in his two greatest achievements – this movie and OUATITW.

LikeLike

Terrific review Colin – I reckoned if there was one Leone film that might appeal then this one, with its strong connections to Ford and Ireland, might be the one!

I agree that the long cut is the only way to make sense of the film, though it also, as you say, adds even more layers of confusion especially the John / Sean overlap. In one of the documentaries Glenn Erickson (aka DVD Savant) constructs an elaborate and fairly persuasive theory about its meaning and about the theme of betrayal extending beyond politics to the personal in terms of the love triangle. I don’t buy it 100% but it certainly make emotional sense even if rationally it is a bit porous. Like ONCE UPON A TIME IN THE WEST the truth is to be found in a dream / nightmare remembrance and one can certainly see how Leone moved from this to the even more convoluted structure of ONCE UPON A TIME IN AMERICA with the sense of guilt leading to a confusion of identification and even identities.

Of the potential English title I think ONCE UPON A TIME IN THE REVOLUTION is probably the best though the Italian is impossible to translate (it’s derived from the phrase, ‘Giu la testa … coglione’, which is very Roman and should be more or less be translated (pardon my ahem French) as ‘Get your head down … dickhead’).

Great stuff mate.

LikeLike

Hi Sergio. The film really is open to multiple interpretations in my opinion – I’ve heard so many posited and some seem more persuasive than others. The name business is fascinating though – not to mention the additional link to Ford and The Informer by having David Warbeck’s character credited as Nolan. In a way, I like the fact we can’t be completely sure about anything.

Regarding the title, Once Upon a Time in the Revolution does have a certain attraction with its allusions to his previous movie.

LikeLike

THE INFORMER sort of has the same function as PURSUED does in ONCE UPON A TIME IN THE WEST in terms of character development. I grew up with spaghetti and spaghetti westerns (ho ho) and so its built-in to my viewing DNA I suppose but this does feel very different from most of the films that the success of FISTFUL OF DOLLARS spawned. The reason I find it so effective is because we see this progress toward this strange, melancholy, oneiric style that completely overwhelms the nostalgia of ONCE UPON A TIME IN AMERICA, which is an incredible movie, a real masterpiece in my view, but also incredibly hard to take. Here the ambiguity seems to suit the complexity of the subject matter in terms of our relationship to stories about revolutionaries / freedom fighters / ‘terrorists’ so in that sense the French title ONCE UPON A TIME … THE REVOLUTION (according to Frayling it did well in France) seems especially appropriate – but for years I only even saw it in English as FISTFUL OF DYNAMITE and I still liked it in the shorter version.

The sequence in which Steiger’s family is found murdered in the caves, which has an echo in GOOD, BAD AND THE UGLY, immediately evokes the Fosse Ardeatine incident in which the Nazi killed over 300 people as a reprisal and I still find that very powerful and is not really something you could have in a plain shoot’em up that’s for certain (the incident was filmed directly as MASSACRE IN ROME by Cosmatos the following year).

LikeLike

Yes, I’ve seen Massacre in Rome and the allusion to the incident depicted, while I missed mentioning it, is indeed a strong one.

In a sense, I grew up with spaghetti westerns too – I’d seen this film and the Dollars trilogy at a fairly early age. At that time, spaghetti westerns and the classic US variety were all just cowboy pictures to me. It was only as I got older that the difference became more apparent. In some chats I’ve had with Blake Lucas a very interesting point was raised, namely the contrasting attitudes of the US and spaghetti westerns in relation to violence and killing. Generally, the Euro westerns have taken a more amoral, casual approach to killing and what it means to the victims and perpetrators. It’s an aspect that I’m not that fond of myself, and I think that’s why I find myself drawn to Leone more than other directors. In Once Upon a Time in the West and A Fistful of Dynamite in particular there’s a very different feel to the violence. It’s seen to have consequences for all concerned, and isn’t especially glorified. That, as much as anything, forms a closer connection between Leone and the classic Hollywood directors for me.

LikeLike

I agree completely Colin – there’s no question that they Spaghetti films were generally much more violent and cynical too – downright nihilistic a lot of time in fact! And it’s a strength of this film that it tries to deal with the end of violence

LikeLike

I think it shows Leone’s maturity as a filmmaker, his acknowledgement that violence for its own sake, or simply the sake of entertainment, shouldn’t be seen as an end in itself.

If the movie was deconstructing the myth of revolution, then Leone was deconstructing the myth of the spaghetti western, and by extension his own myth, here too.

LikeLike

I think Leone really wanted to move on – it’s interesting that between this and his final film he pretty much just produced (very popular) comic films made by Carlo Verdone, which are well above average but are very modest films none the less (Verdone is a huge star in Italy but only there I think).

LikeLike

I think it’s just something else to admire about Leone – his desire to avoid simply retreading the same ground. Whilst a part of me wishes he’d directed more films, another part is happy that he stuck to his guns and tried to develop as far as possible.

LikeLike

When this film was first released here, it was marketed as a comedy-western and the accompanying poster/advertising material appropriately confirmed this ; local critics that I respected, were amblivalent about it; I was not overly impressed by Rod Steiger’s uneven performances in films; and when I discovered the alternative title was “Duck, You Sucker”, I was certainly turned off.

From your enthusiastic review of the film, it would appear that there is a lot more to the film than at first glance.

LikeLike

Rod, I can see how the film may have been marketed as a comedy western. The US poster certainly comes close to encouraging that view –

Also, as I mentioned, the first half of the movie is much lighter in tone before taking a serious turn in the latter part. I have found Steiger problematic at times, lacking subtlety when it was needed, but he’s good in this film and really produces the goods as the story wears on. If you haven’t seen the film, then I heartily recommend you check it out. Bear in mind though that it takes some time to hit its stride – but it’s worth the wait in my opinion.

LikeLike

Colin, I share your appreciation for A FISTFUL OF DYNAMITE. The film never receives the attention it deserves and your perceptive review goes a long way toward correcting that. Personally I think Rod Steiger relishes his role and gives the best performances of his career. It’s an operatic performance, not unlike Leone’s direction. They should have worked together again. I’m fond of this film and I think as highly of it as you do for all the reasons stated in your review.

If you like A FISTFUL OF DYNAMITE consider watching films made by the Mexicans about their revolution. Their preoccupations are very different from American and Italian versions, which I find infinitely more interesting. By the 1930s, the Mexican Revolution had become a film genre in that country. The genre has many of the attributes of the American western, but it is not limited to that. A good place to start would be Fernando de Fuentes’ historic Revolution Trilogy: El Prisionero trece / Prisoner 13 (1933), El Compadre Mendoza / Godfather Mendoza (1934) and Vámonos con Pancho Villa / Let’s Go with Pancho Villa (1936). These early talkies were made by people who either fought in the Revolution or lived through it, and they knew whereof they spoke.

One of Mexico’s greatest directors, Ismael Rodríguez cast Pedro Armendariz as Pancho Villa in Así era Pancho Villa (1957). Instead of trying to do a definitive biography by compressing a life into a short narrative film, Rogriguez decided to recreate different circumstances and events in the life Villa allowing for gaps in the narrative, which taken altogether opens up the Revolution and highlights others in his orbit. So successful was this widescreen, Technicolor epic that Rogriguez and Armendariz followed through by turning it into a trilogy with two more episodic films, Pancho Villa y la Valentina (1960) and Cuando ¡Viva Villa! es la muerte (1960).

Long before he became known as M’Apache in The Wild Bunch, Emilio Fernandez had fought in the revolution with Villa. He fled to southern California and started working in films before a change in government enabled him to go back. As a director, he became the John Ford of Mexico, making films about social injustice and the rural poor, with great playwrights and novelists like B. Traven and John Steinbeck collaborating with him on the scripts. Rodriguez made several films about the Revolution.

One film that must have surely influenced Sergio Leone is José Bolaños’ La Soldadera (1967). For this story about the women soldiers, Bolaños’ worked from Sergei Eisenstein’s notes and storyboards for an episode of Que Viva Mexico! (1932) that Eisenstein was unable to film. Bolaños shot in you-are-there docudrama style like Huston’s Red Badge of Courage.

In contrast, spaghetti westerns dealing with the Mexican revolution seem more preoccupied, understandably, with the European experience than with the Mexican, but anyone who can relate to the masterpiece A FISTFUL OF DYNAMITE will find the Mexican films equally rewarding.

LikeLike

Good to hear from you Richard, and thanks very much for that detailed response.

I will have to admit that I am shamefully ignorant of Mexican cinema outside of references that I’ve come across when reading round the subject of westerns. I am of course familiar with Emilio Fernandez as an actor, and I have seen references to his early life. I was aware, again through reading, that he is highly regarded as a director but I’ve never had the opportunity to sample his work.

Thanks again for offering so many pointers and recommendations for where to start with Mexican filmmakers and their take on their own revolution.

LikeLike

Colin, this is definitely one of your very best pieces–I can’t think of one that I have liked more. You evoked the film that I too love with so much insight as well as feeling that it moved me just to think about it and maybe encourage another viewing soon as I haven’t seen it in awhile now.

I’m very much in harmony with what you say and what others have said. I too am not much of a fan of Italian Westerns though I have tried. Recently, the release of DJANGO UNCHAINED prompted a local theatre to a run of the original DJANGO (1966?) directed by Sergio Corbucci so I grabbed the opportunity to see it as I’d always wanted to–it was in Italian and subtitled, which I thought helped, and Corbucci is plainly a talented director, but I wouldn’t say anything about it was especially brilliant and it had the same mix of extreme violence and high body count with simplistic politics (however much I may sympathize with those politics) that characterize so many of the films. Leone is much more complex. But I will say that over time I’ve become less enamored of the Dollars trilogy and am glad he could find a more serious tone in ONCE UPON A TIME IN THE WEST, the present film, and then in ONCE UPON A TIME IN AMERICA, which on first release I thought even surpassed those two earlier works though I’m not so sure about this now. By the way, I prefer the title I originally saw it under on first release here–DUCK, YOU SUCKER (or GIU LA TESTA) as I believe it was opportunistically renamed A FISTFUL OF DYNAMITE after initial tepid boxoffice in hopes that a reminder of the director might be good for a few dollars more.

Can’t add much to what you wrote. Re the two main characters, I don’t think it’s too much to see them and their relationship as so well-realized that Leone can be credited with a genuinely beautiful variation and reimagining of Don Quixote and Sancho Panza, which he surely had in mind. And you are right about Rod Steiger–he is so often an immoderate actor and hampers my view of him somewhat (he himself seemed aware of it–in an interview once, he said, kind of proudly “He gave a restrained performance–they don’t say that about me very often”) but he can change registers and does play both in this movie and to great effect, very amusing in the comedic parts early on and also playing well the quiet deepening of Juan later. By contrast to Steiger, James Coburn is an actor I generally do like, though how could he could be is really measured best by these two movies made close together–this one and PAT GARRETT AND BILLY THE KID, in both of which he is superb. Sean (will get to the name in a moment) is a more sympathetic character than Pat, though they both encourage a very complex response and an inwardness in Coburn he did not have enough opportunities to display. I do think of Coburn as especially soulful here, though he doesn’t play Sean sentimentally. But either performance could be considered his best; it would be very close for me, as those two films–genre standouts in unhappy times–also are.

That’s allowing DUCK, YOU SUCKER is a Western. One may think of it that way, though its two non-American heroes in Mexico make it a touch marginal to the genre, much as one might say of, for example, WAY OF A GAUCHO. I’d tend to claim these for the Western poetically.

I especially enjoyed the discussion here of the scene in which Steiger asks Coburn his name and he first says “Sean.” I think you are right about the way Coburn plays it. I think Sean is his name and he wants to distance himself from it, as it is the more Irish version of the name so ties into his past, given that Sean and John are interchangeable as you say. This is indeed one of the superb moments of the movie. There’s a tremendous, beautifully modulated buildup to that first flashback with Morricone’s wonderful music with the film now well along–it so powerfully changes the movie’s tone and shows Leone at his peak, I believe.

I don’t think the friend is named “Sean.” I think “Sean” in the music refers to Coburn. Guess it could be argued but the friend is never identified by name at all. By the way, a problem with the film (though I won’t say it’s a weakness). On original release the full final flashback was not there so I spent years thinking the friend was the girl’s brother as well as Sean’s friend. Now, with that scene restored, we need to read the back story a little differently and it was hard for me to make the adjustment when I saw it, though you are right it makes the back story even more complex.

Anyway, mainly wanted to say how much I enjoyed this piece on a richly deserving movie.

LikeLike

Blake, thanks very much for that comprehensive, and extremely complimentary, response.

I remember, as a youngster, being thrilled by the Dollars trilogy – the cool nonchalance of Eastwood’s performance and Morricone’s distinctive and very unusual scoring. I still enjoy those films but not the way I did back then. Like Django that you mentioned, I think they’re very well made and entertaining but, despite moments where there is something deeper touched upon, they don’t draw much of an emotional response from me. A Fistful of Dynamite and Once Upon a Time in the West, on the other hand, reveal new layers on each subsequent viewing and this marks them out as truly great works. It’s interesting too that neither film, nor Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid which you mentioned, opened to universal acclaim yet saw their reputations rise over time.

I guess you’re right that a purist perspective might lead one to say A Fistful of Dynamite isn’t a western according to the strictest definition. However, regardless of the setting and origins of the characters, in theme, tone and at heart it must surely be included in the genre.

LikeLike

What you said about the Dollars trilogy is what I feel. I saw them in reverse order so the best of the three THE GOOD, THE BAD AND THE UGLY was the first one I saw and felt like it was a breath of fresh air for the genre and enjoyed Eastwood for the same reasons you did. And I still think this one especially is an excellent movie, just not so great as I thought it was then. In the same way, I’m more ambivalent about Eastwood and you’ll remember I said this commenting on your top Western stars piece, that I wouldn’t have voted for him even though I acknowledge he is the dominant star of the post-classical Western. I’m frankly glad it was Bronson in ONCE UPON A TIME IN THE WEST and Coburn in DUCK, YOU SUCKER instead of Eastwood.

Despite my reservations about Italian Westerns, ONCE UPON A TIME IN THE WEST has remained my favorite Western post-1962. I do believe Leone carved out his own path in cinema, more than simply being the best of Italian Westerns, even if he made his way in them.

LikeLike

Frankly, and this is no criticism of his three roles for Leone, I couldn’t imagine Eastwood in either Once Upon a Time in the West or A Fistful of Dynamite – I think his presence would have resulted in very different films.

LikeLike

Saw it at the drive-in back in the day, then again last year. I must admit that Rod’s over the top acting wore thin with me many moons ago. Thank goodness Coburn helped balance the film out. I do like the look of the film and Leone is always worth a gander. Nice review.

LikeLike

Cheers, Gord, this remains my second favorite Leone movie.

LikeLike

I grew up with the MGM 2003 UK DVD release and only found out about the many different versions after going to see it at the cinema in 35mm and being surprised by some huge differences (such as cutting the opening urinating on ants). However whilst researching the differences between versions, something I haven’t managed to find anything about is the use of sound at the end. In the 2003 DVD there is no accompanying sound effect when John blows himself up, or dialogue when Juan shouts just before, and there is no line of voiceover saying “What about me?” as the title appears. I’m probably biased towards the version I am used to and grew up with, but personally I find this version of the ending far more powerful having the diegetic sound removed to emphasise the weight and importance of the situation. But as I said, I have not found anything else about this specific difference online (although plenty about the flashback at the end), so do any of you know if there are any other versions with the lack of sound at the end?

According to DVD Beaver (http://www.dvdbeaver.com/film/DVDReviews23/a_fistful_of_dynamite_blu-ray.htm) the 2003 “DVD’s mono soundtrack isn’t super but at least it is the original mix” yet still no mention of the sound difference at the end. If it’s the original mix, then surely that’s the ‘intended’ version? But I think I’ve got lost with all the different versions by this point.

LikeLike

I can’t enlighten you on that, Ewan – I’m sorry. However, maybe someone else who reads this may be able to clarify things a bit more.

The various cuts and versions of Leone’s films in general is enough to make your head spin and I’ve kind of given up trying to keep track of all of them – it’s practically a full-time job in itself!

There’s probably an interesting discussion to be had on preferred versions of movies, and I suspect many people will be swayed (as I think I would be myself) by the one they saw at a formative stage in their life.

LikeLike

Hello again, I’m just coming back to this post after a few years both because a few days ago I received an email about some recent activity, and I was coincidentally in Dublin last week visiting a couple of the filming locations from A Fistful of Dynamite – Howth Castle and Toner’s Pub.

Howth Castle is a bit out of the way but still nice. Toner’s was absolutely packed when I went, but I hope to return during an off-peak time when it’s a bit emptier and I can take some pictures too. For any fans out there that pass through Dublin, I definitely recommend visiting Toner’s – Even 50 years on it’s still got the distinct features (e.g. the mirror) that make it recognisable as a location from the film if you know what to look for 😉

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks for that, Ewan.

I’m in Ireland for some time every year but I rarely seem to get the chance to spend time in Dublin – must try to do so this summer actually.

LikeLike

I’m glad to see this Leone film get some love. The first time I saw it I was blown away. Steiger and Coburn are so good in this. I’ve I always liked Steiger since I saw him in one of my favorite epics as Napoleon in ‘Waterloo’. Leone really directed them well in this and I love his contributions to the genre. His last one after this ‘My Name is Nobody’ is wonderful and hilarious.

LikeLike

To be honest, Chris, Steiger is someone I can take or leave depending on the movie. He could turn in fine work when he was reined in but there were times (too many arguably) when he seemed to know no restraint and allowed his performance to become far bigger than the role, and maybe even bigger than the picture itself.

LikeLike

I meant to add in the last post the high regard Leone. ‘Once upon a time in West’ is one of my favorite movies of all time.

LikeLike

I’d agree with that, Chris. It is a genuinely majestic piece of work and highlights the gulf of class and sensibility between Leone and other directors of the spaghetti western – there is no comparison.

LikeLike

Also the blu of ‘Dynamite’ is essential: good picture and sound, longest version, great extras and Frayling’s wonderful commentary. I love all his Leone commentaries plus the one he did on ‘Magnificent Seven’. His talks really enrich these wonderful movies. His book on Leone is frankly the last word. Leone’s movies were made for HD.

LikeLike

Yes, I have that book myself. It is probably the essential work on the director.

LikeLike