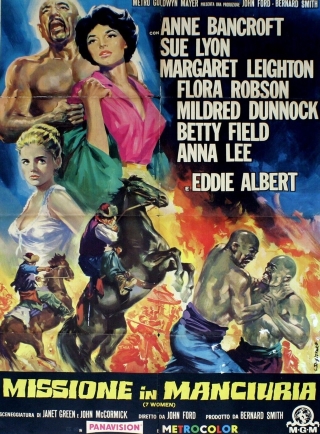

The final films of the great filmmakers can be a mixed bag with truly memorable works being very much the exception. Not unnaturally, a certain tiredness can creep in, the quest for originality may bring about misfires or confusion. This is all to be expected when careers are long and that very longevity has had to confront changing trends and shrinking budgets. Those last two factors are hard to avoid but the real artists are forever chasing truth in their art and sometimes they can touch upon it in spite of the constraints imposed by the passage of time. Of course the great artists will already have found their truth and if we (or they) are fortunate, then that truth may find expression as a distillation of the themes explored in their peak years. John Ford was without doubt one of the greats and maybe even the greatest. His final movie 7 Women (1965) has not always enjoyed a strong reputation yet I believe it deserves better, and I also see it as providing a fine coda to a remarkable career.

A lot of the critical dissatisfaction with 7 Women stems from the fact that it appears to be something of an atypical Ford film. It is not set in the American West nor is it focused particularly on what might be termed the American experience – it is not easy to frame as one of his examples of myth building. It does not allow for the inclusion of any of his Irishness, not even in its minor characters, and there is little if any examination of masculinity. Still, to criticize it on those terms is to succumb to no more than a superficial reading of Ford. Sure he blended the aforementioned elements into so many of his films, almost all of his best works contained one or more of them – How Green Was My Valley is one the major titles which stands out as not doing so. To focus on that would be to buy too completely into Ford’s own blarney and “I make westerns” shtick. The fact is he was most interested in the cohesiveness of communities, questions of faith and duty, and the truth lurking behind facades. 7 Women keeps the spotlight firmly trained on all of these.

The on screen text informs the viewer that the story is taking place in the years before WWII, in 1935 to be exact, in a remote and far-flung region of China. In essence, it is the frontier, just not the frontier of the Old West that one so readily associates with Ford. Instead this is the Far East yet it is no less a frontier for being located there – it is still the edge of civilization, that untamed region where law is but a casual interloper at best. Officially, this should have been a time when the warlord era had come to close in China, but that’s not the case here. The specter of Tunga Khan (Mike Mazurki) hangs like a threatening storm over everybody’s head. The fear of pillage and atrocity is never far from the thoughts of the occupants of the evangelical mission run with clear-eyed determination by Agatha Andrews (Margaret Leighton). Despite this messianic zeal, there are deep and powerful undercurrents raging within the mission and its members. The one married woman present (Betty Field) is pregnant while approaching menopause and her ineffectual husband (Eddie Albert) is a dithering dreamer, while Andrews is waging a private war with her own sexuality and struggling against the temptation represented by her young assistant Emma (Sue Lyon). Into this increasingly tense atmosphere arrives the new doctor, the brash and worldly Cartwright (Anne Bancroft). Her unorthodox – at least from Andrews’ perspective – approach to life helps to raise an already simmering emotional temperature while an outbreak of cholera sees the balance of power begin to slide. However, the ultimate challenge, not simply to Andrews but to all of the denizens of the mission, will come when Tunga Khan’s rampaging bandits crash through the gates and take control.

Ford’s films were always liberally sprinkled with grace notes, quiet and reflective sequences that served to bookend the more vigorous passages. In a movie which has been criticized for its visual modesty the violence and terror of the bandits’ assault is calmly foreshadowed by Bancroft and Albert gazing at an evening sky bathed in the boiling and throbbing flames cast by a neighboring settlement being put to the sword. Moments like that do not reach the levels of splendor which were attained in masterpieces such as She Wore a Yellow Ribbon, for instance, and it would be foolish to try to draw any such comparison. Nevertheless, within the context and framework of the movie before us there is still the classic Fordian human bonding on display. The same can be said for the scene with Andrews and Cartwright sitting below the tree in the courtyard in the wake of the cholera episode, a small moment of shared compassion that rounds out the characters. Even simple shots such as that of Cartwright drawing on a cigarette behind the shade of a mosquito net, separate, self-contained and lonely, are effective due to their quiet simplicity. Color is used sparingly but intelligently as well. So much of the movie is shot in subdued tones – the cool and severe blues and greys favored by Andrews and her fellow missionaries, the earthy browns of Cartwright. And then the climactic appearance of Cartwright clad in shimmering yellow, with that slash of crimson, a burst of positivity and passion emerging from the darkness as she prepares to sacrifice herself.

I briefly mentioned faith above, and want to return to that for a moment. It’s been said before that religion played a big part in Ford’s work, an assertion I only partially agree with. Is it not more accurate to state that faith and perhaps a broader notion of spirituality were stronger drivers? Religion, and certainly religiosity and sanctimony were never really celebrated. Redemption and the need for renewal, on the other hand, are common features. All of the characters in 7 Women are spiritual searchers of one kind or another. All have come to this spot on the periphery of the civilized world hoping to find that which was denied to them at home. Andrews is dangerously repressed and existing at the border of her own psychological frailty. She has sought alternative fulfillment in religion but has grown aware of the fact it was not and is not enough, and is thus driven out of her mind. Eddie Albert’s Pether has finally married late in life and is busy seeking a fugitive form of contentment in the ersatz ministry he’s building around himself. In the end he chances upon some dormant nobility in his own rediscovered courage. At the heart of it all is Cartwright, a woman who through sacrifice unearths meaning in a life formerly wasted and marked by both personal and professional failure. This cigarette smoking whiskey drinker, contemptuous of piety, hypocrisy and cant reveals herself as a humanitarian in the truest sense of the word.

Anne Bancroft wasn’t the first choice to play Cartwright. Patricia Neal had started work on the movie but suffered a stroke so a replacement had to be found. Ford is on record as not rating her work but he was wrong about that – she has grit and toughness with just enough of that hint of vulnerability to fuel the soulful regret that defines the character, a woman wryly reconciled to the impishness of fate. Much as I admire Neal as an actress, I doubt she could have done better in the part. Margaret Leighton also fully inhabited her role and touches on some of that inner fragility she used so expertly in Carrington V.C. and The Sound and the Fury. Among the other cast members Flora Robson brings out that well-bred restraint that was her trademark. And it’s a pleasure to watch Anne Lee in one final Ford movie – a woman I will forever think of as Bronwyn in How Green Was My Valley and Mrs Collingwood (“All I can see is the flags”) in Fort Apache.

7 Women has been one of John Ford’s most neglected films, languishing in the critical stakes and seemingly forgotten when it came to home video releases. The absence of an official release on any form of physical disc was nothing if not conspicuous. Recently though, the Warner Archive Collection has made it available on a beautiful looking Blu-ray. Having seen the film multiple times over the years in less than stellar presentations, I can say this new release is a revelation, one which effortlessly elevates the movie. I sincerely hope this fine version prompts a reassessment of what to me are the clear merits of Ford’s final movie.

As this will be my final posting for 2025 I want to take the opportunity to wish all the visitors and contributors to this site over the last 12 months a happy, peaceful and prosperous New Year. Thank you all.

As an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases made through links on this page.

I shall get the disc now, thanks Colin. I haven’t seen it in over 30 years but am really intrigued. Have a great New Year, chum.

LikeLike

Happy New Year to you too, and I hope you like the film when you get to it.

LikeLike

Interesting thought that: leads me to wonder should Hitch have retired after Psycho? Its an interesting thought experiment, working out from a director’s filmography which one he should have bowed out with, for posterity’s sake. The arguments would be endless…

Happy New Year, Colin. Hope 2026 is a great one.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Happy New Year!

I’m glad Ford signed off with this film, it explores the themes he so frequently returned to, quite successfully in my view, and if it comes across as stylized, well it’s stylized in his way.

As for Hitchcock, I’d be displeased if we had not been left with The Birds and Marnie, especially the latter, but I would say that followed is far from essential.

LikeLike

I think Hitchcock picked the right moment to retire. His two 70s movies, FRENZY and FAMILY PLOT, are worthy entries in his filmography.

LikeLike

I did not like Psycho or anything other than Foreign Correspondent and Rear Window other than his Cary Grant pictures, which is clearly the way to identify them.

LikeLike

They are ok, but I wouldn’t lose any sleep if they hadn’t been made either, everything after Marnie is part of a process of diminishing returns. Since September I have been working my through a selection of Hitchcock movies at random and in all that time I have not once felt the urge to view Frenzy or Family Plot again. I did look at Topaz the other day though – it remains leaden and largely colorless with an extra half hour tacked on at the end for no good reason.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hitch was wildly uneven throughout his career. He made two duds in the 60s, Torn Curtain and Topaz. But he’d made plenty of duds before. They’re no worse than Rope or Under Capricorn.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Oh I’d say Topaz is a lot worse than either of those, which suffer mainly from the limitations he imposed on his storytelling with the long take experiments. They at least had better stories to tell and much more interesting casts. And for all its issues, Torn Curtain also had stars, even if they weren’t ideal casting, and a tighter plot too.

LikeLike

I recently went through ‘Family Plot’ and ‘Frenzy’ and found again their decent points. I really like the cast in ‘Family Plot’ as Bruce Dern and Karen Black are favorites from that time. Plus William Devane is a criminally underrated actor (check out his superb JFK in ‘The Missiles of October for proof). ‘Frenzy’ is a nasty piece of work and I find it intriguing for that. ‘Topaz’ I have no great defense for but Leonard Maltin makes a nice try in his video essay on the DVD/Blu. I still like the flowing dress scene which is a great set piece.

LikeLike

Fair points and I don’t deny all of those movies have elements and/or sequences that are worthwhile. Still, viewed overall and in relation to the body of work that preceded them, what they offer is thin.

On Devane, I very much enjoyed his recurring cameo appearance as the cop turned shrink in the Jesse Stone TV movies from the Robert B Parker books.

LikeLike

Yes he was wonderful in that and those were excellent shows.

LikeLike

I also meant to add those that ‘enjoyed’ Barry Foster’s lowlife character in ‘Frenzy’ might want to check out his compelling portrait of a 20th century bad man whose decisions changed the world-Kaiser Wilhelm in the excellent series ‘Fall of Eagles’.

LikeLike

Topaz’s biggest problem is the lack of a charismatic star. The main character is a French spy. I keep imagining how this movie might have been with Alain Delon in that role.

They needed a guy who spoke English with a French accent. Delon did his own English dialogue in Joy House. He spoke excellent English. With a French accent, because the guy was French! With a sexy dangerous charismatic star like Delon it might have worked.

LikeLike

Happy New Year! Excellent review. As a Fordian will have to get the disc. WAC does such good work. I picked up two Ford 4K/Blus in the last year the WAC ‘The Searchers’ and Kino’s ‘Donovan’s Reef’ and found them mighty impressive.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Happy New Year, Chris.

Yes, any Ford fan owes it to himself or herself to get this – it’s been a long wait for a release that does it justice.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I saw “7 Women” at the Harvard Epworth church in the early ’80s. The minister there featured a very eclectic selection of films which were projected on a very large screen. I thought it was a very fine film and that Ann Bancroft was perfect. I recently watched the famous ending. One question our host asked before the film started was, “What does [Bancroft’s] yellow robe symbolize?” He never answered his own question and I’ve never been able to figure out what its meaning is.

LikeLiked by 1 person

For what it’s worth, my view is that Bancroft’s Cartwright has been seeking to distance herself from her former life by coming to China in the first place. Her past has been unsatisfactory, both personally/romantically and, I think, professionally too. All of this can be associated by her with her femininity, and her new beginning in China represents something of a rejection or refutation of her past failures as a woman. She has adopted (certainly for the time portrayed) a quite masculine mode of dress and indeed behavior. That too though is shown to have achieved only limited success – is she really fulfilled in any real sense?

When she dons the much more feminine kimono and trappings to sacrifice herself for the others, she seems to me to have reverted to her original state, accepted how her femininity can be used in a way which will unquestionably benefit her former companions, and perhaps bring a sense of redemption to herself. And of course yellow is indicative of rebirth and renewal, of spring and sunshine and new beginnings.

Or all that may be reaching too far.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you, Colin, for sharing this profound and accurate insight.

LikeLiked by 1 person

As for final films by great directors, Fritz Lang ended his career on a very high note indeed with The 1,000 Eyes of Dr. Mabuse. A huge hit in Germany, successful enough to spawn half a dozen sequels.

LikeLike

Just a note on the date for 7 Women. I believe it should be cited as a 1966 film and it usually is. IMDb does give 1965 but they always base this on where a movie had a release anywhere and the film did play in Japan late in that year. But wide release everywhere else was in early 1966. Most sources will cite dates for films based on their release in the country that produced them, and I tend to go along with that. This is not a big deal though. It can be done anywhere–probably doesn’t affect how we place the film in time.

This is short just to make sure my comments are getting through. I had to work to get back into Word Press, and wanted to do it especially to comment on Colin’s piece on this film when he wrote it, so this is a further test. Then will continue.

LikeLike

To be honest, my initial instinct was to go with 1966 as it’s the date I had come across most often in the past. In the end I settled on 1965 due to the IMDB listing.

LikeLike

Seems like that came through OK. One more brief comment before I get into the film and Colin’s excellent piece, which though brief, is rich and allusive, about Ford and the film.

It’s not strictly correct that this never had any form of physical release on home video, even though it does feel like that by now. 7 Women did have a release on Laserdisc years ago during the relatively short period when those were made. Most of us never got it, and then that ended. That doesn’t make what Colin wrote incorrect because through all of the years of DVD and now Blu-ray, it was a mystery why Warner Archive never put it out. It seemed like they put out every run of the mill movie they owned on DVD, but not this one, the last film of John Ford.

So this is cause for celebration. I bought this Blu-ray right away but haven’t watched it yet. I’ll see it on Ford’s birthday (February 1, always watch one of his films then), and this is its 60th anniversary year, so a good time. I really look forward to it, and hearing how beautiful this looks now is heartening because it is an exceptionally beautiful work, a masterpiece even on a purely aesthetic level before one gets to its piercing soulfulness.

LikeLike

Fair point on the laserdisc, which I was not aware of. Thanks for bringing it to my attention – I wonder if the rather weak Spanish DVD which was available derived from that source.

LikeLike

One reason I wanted to be able to comment was that I knew Colin would write in the film’s favor (he had suggested a high opinion of it earlier) and anticipated whatever he wrote might warrant support. I felt that some of the comments might get after the film for not being that good, based on its initial reputation and commercial failure.

But that hasn’t happened over the time this piece has been here. I have a feeling now that, understandably, not many people here have seen it, because as emphasized, it has not been out in the home video market, which is how most of us are seeing older films now. So will just add to what Colin already talked about–if you haven’t seen it, put aside any preconceptions about what a Ford movie should be and and just go to it as it is, and at this point, 60 years on, you’ll likely appreciate it if you have ever loved Ford.

It’s not strictly true that the film has a bad reputation–it’s more mixed, as Colin suggests if I’m reading him correctly. It was mostly in America, Ford’s home country, that it was completely dismissed back in 1966. Elsewhere, in England for one place, and especially in France where it rated very high (6th place and highest American film in the top ten for Cahiers du Cinema for example), it actually was well-regarded and played successfully. We must remember the mid-60s was a very volatile time in cinema, a time of transition, and a lot of work was misunderstood, especially by the old masters. Colin treats this idea a little at the beginning of his piece and I want to come back to it separately because it’s interesting to me, but will stick to the present movie for now.

In any event, the truth is that most Ford aficionados love it, and though Colin didn’t mention this, Ford himself regarded it as one of his best films. That’s only one reason why it was a good movie for him to go out on–the haunting finality of its final minutes and its last image are better ones, and there are plenty of other reasons too. In Sight and Sound poll in 2023 of best films, one person, female (I believe it was in critics’ poll) named it first among a group of mostly more modern films, many by women like Akerman (Ford’s film did get a number of votes) and stated simply: “The most beautiful movie ever made.”

We could talk here for many days and nights about what Ford’s world is and what it is about, but I thought Colin did a good enough job here of cautioning that if it is not in a certain genre (Westerns, specifically), not about America or Ireland, not focused on men, and all of those superficial readings of him, it doesn’t really represent him. I believe we should give the widest possible latitude to an artist as great as this, and moreover, his films show it–just on men and women for example, start thinking of the women in even his more male-centered movies and it shows how well he understood women and how well he did with them (just consider the five with Maureen O’Hara for a start). In my view of his films, the first and last of his certain masterpieces, Pilgrimage (1933) and 7 Women, are both focused centrally on women. And they are far from the only ones.

There are really so many threads and motifs in Ford, and in any event, Emma leading the children in one more rendition of “Shall We Gather at the River” in the perilous moment of the epidemic by itself kind of seals it as one more Ford film, doesn’t it?

Before any more specific comments I guess I might acknowledge something. Colin wrote: “Without doubt one of the greats and maybe even the greatest.” After so many years of living with him, seeing most of his movies so many times and always wanting to go back to them, I won’t be even that equivocal. For me Ford is easily the greatest filmmaker ever (and there are a fair number of great filmmakers, and many great artists among the many collaborating contributors to movies too)–I actually consider him probably one of the ten or twelve greatest artists ever in any medium. His work is that rich, deep, expressive and eloquent. But simply for what he does as a director, it’s perhaps especially for one reason: while he is very deliberative in creating images and scenes (even though he mostly did it on the set), and they might even be considered to have a painterly, very conscious quality, they don’t play that way–within them, everything and everyone feels very spontaneous and alive, animated and in the moment.

So, for example, the last image that Colin shows in the piece (Bancroft in the hallway in silhouette) is often presented to evoke the film, understandably as it is stunning and shows that after 50 years Ford could still find the kind of moment no other director could. But see the film: this image does not just lay there–it’s there fairly quickly and then gone within a series of images that are propelling the movie forward to its end, beautifully carried too by one of Elmer Bernstein’s most sensitive scores (music is always great in Ford). Rather than being just beautiful pictures, Ford’s films move and it always feels like his films are alive. One might also think of how the end of the film is set up–the vibrant color of the kimono that Colin sensitively talks about as a kind of marking point also comes in when there is a lot of movement at that point in the film, and the prefiguring of the end–with the themes of community and spirituality that he talks about in the piece becoming powerful–follows not much later (as I’m recalling–has been a while but I’ve seen it many times) coming in a scene that was, according to Joe McBride’s biography, improvised on the set by Ford–this is the very moving last scene between Dr. Cartwright and Miss Argent (Mildred Dunnock), which shows how bonded the two now are (next to Cartwright, Argent is the film’s most sympathetic character). Several key things are quickly said and then there is that affecting exchange of embraces between the two women. It just doesn’t happen like this in other people’s films, meaning this kind of scene and this kind of gestural beauty. Other directors do create moments that are this great when they are at their best, but not of just this kind of artistic character, and not so often through a whole body of work..

While I’m on the subject, a few words on the actresses and the characters. I wanted to mention Dunnock because along with Margaret Leighton, I believe she stands out in a group of mostly outstanding performances (would qualify a little with Sue Lyon, as most do, but I’ve gotten used to her and feel maybe Emma is not really very deep), leaving aside the Mongols (Ford favorites Mazurki and Strode cast in a way that makes one not take them seriously but Ford often made the bad guys colorful and kind of comic but just really bad, if you think of Westerns like My Darling Clementine, Wagon Master and The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance). I agree not only about Leighton but really appreciate that Colin showed her character some sympathy–Andrews is a nuanced character and deserves that sympathy and it is hard to see her psychologically and emotionally disintegrate in the way she does; the moment of communion beneath the orange tree between her and Cartwright is very moving, two characters on separate journeys, both of them disappointed by life, and antagonistic mostly but here reaching for understanding of each other. I’m really glad this scene is singled out in the piece.

Colin, while I agree with what you say about Leighton and Andrews (and most of what you talk about), your description of Cartwright is one I haven’t seen before and felt kind of provocative to me. Yes, it’s true she is alienated, but that her life is “wasted” and that she is a “failure” is questionable even if she sees herself this way. She is a doctor and has surely helped many people, even while being unsatisfied in her own life. I do believe you are very much on track though in seeing the resolution as not only one of a sacrificial gesture but a gesture toward community, as that last farewell with Argent shows, and indeed one of the strongest parts of this piece, along with observation of Ford’s aesthetics, is the emphasis on community as a leading theme for him, something I want to take up more but have given this all the time I can now so will continue it later.

I just want to add in context of Cartwright that it was only in the last few years that I read (in another source) that Ford was disappointed with Bancroft. It really surprised me, as I’ve always felt she gave everything he would want in the role, can’t imagine Patricia Neal being this good even though I like her, and in truth this is for me easily Anne Bancroft’s greatest performance in her whole career. You did evoke some of the moments, like her, alone, lighting the cigarette behind the mosquito net. Soulful is the word. Along with community, spirituality is the perhaps the other key to Ford, and the character so piercingly carries this to the final Fordian epiphany.

Hoping not to overstay of course, but one cannot say enough about Ford and this very beautiful last work. And I haven’t even gotten to the subject of late work and last films in general, which is also interesting to me on its own.

So will pick this up again as soon as I am able to do so…

LikeLiked by 1 person

That’s quite a response, Blake – thanks for taking the time to delve into a lot of different ideas there.

The only thing I want to add to that just now is the point you raised about Cartwright. Regardless of how I may have expressed it, I would like to clarify that I don’t necessarily regard her as a failure myself, more as a female version of those colonial types that cropped up in a lot of early 20th century literature and head off to far flung locales in search of a meaning to their lives that seems to have eluded them – that aspect comes from the way the character refers to herself, there’s her self-confidence and self-belief, her frank acknowledgement of her medical skills, but the disappointment she carries around and the regret cloaked in cynicism is another acknowledgement that her life has not panned out the way she wanted it to. I think she regards herself as unfulfilled and even if she is judging herself more harshly than she needs to, that aspect is key to understanding the reasoning behind her final sacrificial act.

LikeLike

You say it very well here and I agree completely with this as you say it now.

You note I know that I did say she was “unsatisfied in her own life” so I already partly agreed with you before and didn’t feel you were misrepresenting her. But saying more about it in the way you did here fully clarifies the way we should see her.

LikeLike

Yes when reads the Ford books (I admit my shelves groan under them) ‘7 Women’ splits the main authors McBride and Tag Gallagher are backers while Scott Eyman and Lindsay Anderson aren’t. I’ll have to read what Janey Place says again. WAC really does right by Ford. All of their releases have amazing transfer on Blu. After this they really should think about doing ‘The Fugitive’ with Fonda. That would look incredible. I urge all readers who are Ford fans (guilty!) to support WAC Blu releases of his films as each and every one is a treasure so far.

LikeLike

Also will be interesting if WAC will do Blus of ‘Cheyenne Autumn’, ‘The Informer’, ‘Sgt Rutledge’, ‘The Lost Patrol’, ‘Mary of Scotland’, ‘Long Voyage Home’, and ‘Wings of Eagles’ among others.

LikeLike

I need to rewatch it, but I remember thinking it was an odd choice of material for Ford, who didn’t have much of a rapport with actresses, and this is a film where the female characters dominate (personally, I think Cheyenne Autumn would have been his perfect swan song). I kept thinking George Cukor might have been a better fit. Anyway, I thought it was just okay: interesting, but not one of Ford’s best.

LikeLike

George Cukor and men of the west do not mix.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I thought Heller in Pink Tights was very good, different to Louis L’Amour’s source novel but in a worthwhile way.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Sophia Loren played the guy.

LikeLike

You just beat me to it! I was going to mention Cukor’s Heller in Pink Tights, which I thought was quite good.

LikeLike

Hey, I just realised I own Heller in Pink Tights on DVD but I’ve never watched it. Maybe i should give it a spin.

LikeLike

I always thought Ford’s ideal woman was Maureen O’Hara why he used her so often and well. If one wishes to see Ford’s deft touch with a woman see Henrietta Crosman in ‘Pilgrimage’ from 1933. This is a seriously brillant film and I have no idea why it is not readily noticed as a masterpiece as Crosman is great and Ford’s direction peerless. I too wish he could have gone out on a Western or a story from American history. Two fell through one on Valley Forge and another on the battle of Midway (which he had been at).

LikeLike

“…Ford, who didn’t have much of a rapport with actresses…”

I addressed this in my earlier comment, and obviously I consider this to be completely wrong, even if it’s a common though, very casual misconception.

I won’t cite the many examples (apart from 7 Women) that prove the point, but will just confine myself to one, since Eric Binford favorably mentions Cheyenne Autumn.

Carroll Baker was wonderful under Ford’s direction, at her most natural and appealing and was arguably never better than in that film. Moreover, as I have written before (so copying this from the piece)…”…a Quaker, she is the film’s spiritual center, balancing her priorities, both intimate and communal, with beautiful poise, and its single character who tries to look beyond the troubled present to a better tomorrow.”

So, no George Cukor would not have been a better director for 7 Women–the subject would not have meant as much to him–but conversely, he should be given more credit for his direction of men (as well as women) who are equally good under his direction. Count me as another admirer of Heller in Pink Tights, which for me rates as one of Cukor’s outstanding works and is moreover, an excellent Western by a director not associated with the genre. Most female and male characters are well-realized, and as a peripheral note, from what I understand, though haven’t read it, Steve Forrest’s character was likely the protagonist in Louis L’Amour’s book. He’s still important, Loren perhaps now central, but what most makes it Cukor’s is that the greatest emphasis is on the theatre, a subject that is always close to him.

LikeLike

Totally agree about O’Hara with Ford and ‘Pilgrimage’ being a stunning piece of work. I also think Vera Miles is very moving in ‘Liberty Valance’.

LikeLike

Another superlative performance I meant to add is Jane Darwell in ‘Grapes of Wrath’.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Correct: That was “Both female and male characters are well-realized…”

LikeLike

And I totally agree that Vera Miles is “very moving” in The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance. And I’m glad you called attention to this.

LikeLike

‘Mogambo’ is coming from WAC for all Ford Blu fanatics. Also wanted to praise the WAC release of Robert Taylor. It has ‘The Last Hunt’, ‘Westward the Women’, ‘Devil’s Doorway’, and ‘Ivanhoe’ half off. Great films and deal.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Excellent and very welcome news on Mogambo – long overdue in my opinion.

I have that Robert Taylor set on its way to me as we speak and I’m looking forward to revisiting those titles. I already had The Last Hunt on Blu-ray from Germany but the other movies at a good price was too tempting to pass up.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I thought Mogambo would have been high on their list. Well, welcome no matter.

LikeLike

Yes, when I saw that set I wanted it because of all those great films. So I’m very happy to have it now and go through it. ‘Westward the Women’ even has some nice extras.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Colin, a good and interesting write-up on 7 WOMEN(1965) John Ford’s last feature movie or picture, as Ford would say. Personally, for many years I’ve been interested in the last occurrences of endeavors of all kinds and also the first occurrences of such endeavors. So, your write-up goes right up my lane, and I commend you for taking up for Ford’s last hurrah, although he didn’t plan on 7 WOMEN being his last picture show.

I knew about 7 WOMEN being Ford’s last movie, but I didn’t catch up with it until the cable tv explosion of the 1980’s. I had read that the movie was a commercial and critical flop, but I hadn’t had a chance to view it myself. This movie was the only Ford movie of the 1960’s, other than SERGEANT RUTLEDGE(filmed 1959, released 1960), that didn’t receive a prime-time network television premiere. In fairness to SERGEANT RUTLEDGE, a Warner Bros. release, Warners hadn’t cut a deal yet with the television networks for prime-time network premieres before SERGEANT RUTLEDGE had been licensed for local tv stations to begin showing it. Apparently, the networks weren’t keen about airing 7 WOMEN or Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer(MGM) just finally decided to dump it into the local tv markets in 1972 to get their investment back.

I first viewed 7 WOMEN on Atlanta, Georgia’s WTBS Channel 17 in 1987. Too me, at that time, the movie seemed quite different from the usual Ford movie that I had been used to viewing. I didn’t think it was a masterpiece or one of Ford’s best, but I didn’t dislike it either. I liked some things about it and disliked others. I didn’t view it again until I caught it on Turner Classic Movies(TCM) in 2012. I liked it a little more than I had the first time around, but I still don’t think it’s a masterpiece or one of Ford’s best, but I do think it’s worth viewing and discussing. On another note, I saw a longer version of this movie back in 1987 than I did in 2012. I’ve read that there is 6 minutes missing from the Blu-ray release of the movie that had been shown on tv in the 1970’s and ’80’s. Apparently, MGM had cut the 6 minutes out before its release in December 1965, but had put the minutes back in for the tv showings. This wasn’t unusual, because that has been done a lot over the years. If my memory serves me right, I recall that there were some outdoor scenes of the Mongol Bandits burning a village and of Dr. Cartwright(Anne Bancroft) riding horseback and one of the Mongol bandits(Woody Strode) gives her some wildflowers. Also, a scene where Jane Argent(Mildred Dunnock) has been turned down the opportunity to have her own mission and Agatha Andrews(Margaret Leighton) is happy about that and doesn’t believe that Argent is qualified to lead.

I want to like 7 WOMEN and I do enjoy Anne Bancroft’s performance as the John Wayne of this Eastern. In an interview she said that Ford called her “Duke” throughout the filming of the movie. I get a kick out of when she rode into the mission wearing her Western style hat and riding on a mule. Well, the other women characters are harder for me to contend with, except Miss Ling(Jane Chang), who portrayed a real lady, even after being abused and degraded by Tunga Khan(Mike Muzurki). I realize that Ford liked to work with people he knew, but Mike Muzurki and Woody Strode as Mongols. To me they’re just not believable, and I realize that if this movie was made in 1935, I would overlook it, but it was made in 1965 and there were plenty of Asian actors that could have filled these roles.

As I’ve said, I don’t dislike 7 WOMEN, but I just don’t like it as much as you do, and that’s okay. If we all liked and disliked the same things, it would be a dull world. So, to each their own.

Concerning the release date of a movie, and I agree with Blake Lukas’ statement, “This is not a big deal though. It can be done anywhere–probably doesn’t affect how we place the film in time.” Yes, it doesn’t, so why bring it up. The movie is frequently referred to as a “1966 movie” in the United States due to its domestic premiere date of January 5, 1966, but it is officially dated 1965 in many film archives because of its earlier Japanese release on December 11, 1965. Although, IMDb’s movie release dates can be wrong, but I do know that 7 WOMEN was playing in Toronto, Ontario, Canada on December 29, 1965. I tend to go along with the first release date where people are viewing the movie in theaters, whether it’s in Los Angeles, New York City, or Timbuktu. Of course, that’s just me and to each his own.

Take care and have good health to everyone in this New Year.

LikeLike

Walter, with regard to the footage cut from the movie, this interview with Joseph McBride gives more details: https://oldnew.substack.com/p/ford-focus-joseph-mcbride-on-7-women

LikeLike

An interesting piece, unfortuantley for Ford, you and I, the film is many times too long, and never as salient; a matched set with Cheyenne Autumn, prepared for John Wayne who walked away from it and inadequatley replaced by Richard Widmark.

All of this is conversation,the old man was done and had been for years, but if you choose to deify him, there is plenty on the back burner to choose from.

c

LikeLike

Colin, thank you for the link to FORD FOCUS: JOSEPH MCBRIDE ON 7 WOMEN (1965) an interview by R. Emment Sweeney. I’ve not read Joseph McBride’s biography of John Ford SEARHING FOR JOHN FORD(2001).

LikeLike

I wholeheartedly recommend McBride’s bio. It’s comprehensive, readable and well worth investing in.

LikeLike

Colin, thank you for the recommendation. I’ll seek it out.

LikeLike

Great book. Also like the ones by Eyman and Lindsay Anderson.

LikeLiked by 1 person