The idea that in order to resolve a problem one ought to have first hand knowledge of it appears sound. That’s the theory that Drum Beat (1954) puts forward, that a the best man to negotiate a peace is one who has been intimately involved in the hostilities. It’s a variation of sorts on the notion of setting a thief to catch a thief, only imbued with the kind of latent optimism that characterizes the work of writer and director Delmer Daves. It takes some real events and people from the Modoc War and uses them as the basis for a story that champions the need for rapprochement, hammering home the point that the harder it is to win, the more meaningful it becomes. The movie shares some similarities with Daves’ groundbreaking Broken Arrow, although it’s not as good that earlier film. Nevertheless, all of the director’s westerns are worthwhile in my opinion and even if Drum Beat doesn’t quite measure up to his stronger efforts, that is not to say there is nothing to recommend it.

The movie opens in Washington, in the White House in fact. There’s a marvelous informality to this, something that is hard to conceive of nowadays, as Johnny MacKay (Alan Ladd) simply walks right in and states that he has an appointment to see President Grant. It’s all about a new initiative aimed at bringing the Modoc War to an end. Washington wants to see the conflict resolved through negotiation and diplomacy, and that is where McKay comes in. His brief is to make contact with the Modoc chief Captain Jack (Charles Bronson) and attempt to coax him back to the reservation. MacKay would appear to be an odd choice for the role of peacemaker given his history as a famed Indian fighter, not to mention the fact his family had been slaughtered in an earlier massacre. Yet he’s the one selected and it’s precisely because of his background that he has made the cut. Jack is not the type to be swayed by professional purveyors of platitudes, he too is a man of action and as such more likely to pay heed to someone whose fearsome reputation precedes him. MacKay is of course aware of the magnitude of the challenge facing him and once back on the frontier it quickly becomes apparent to the viewer too. When two antagonistic cultures are living in close proximity then resentment can easily flare into something much more dangerous as a result of pettiness and relatively minor gripes getting out of hand. That proves to be the case as slights and harsh words lead to aggression and then senseless killing, only to be followed up by more tit for tat revenge before exploding into full on warfare. All the while, MacKay has to maintain his own self-discipline and sense of duty, partly as he’s given his word and partly because he gradually realizes that his mission represents the only way out of the impasse.

Drum Beat was the second western for Delmer Daves, following on from Broken Arrow and sharing some common themes, including the quest for some kind of peaceful co-existence between settlers and the native population, and also the idea of interracial relationships. Broken Arrow dealt with both more effectively, perhaps because of the characterizations of Jeff Chandler and Charles Bronson as Cochise and Captain Jack respectively, and also because the leads in both films approached their roles in a different way, but I’ll come to that a little later. Daves would go on to write the script, but did not take on the director’s responsibilities, for the following year’s White Feather and that too is a more satisfying movie all round. While there are aspects of this movie which are less successful, what does work is the director’s eye for a beautiful composition. There are some terrific shots of the Arizona locations on view, the mythic landscape dominating the CinemaScope frame and the frequently minuscule figures within it in a way that recalls Ford.

I’ve read some critiques of the movie that state it presents a far less favorable image of the Modoc than Daves’ previous western. I can see how that impression can be formed and I’ll admit there are some grounds for it, but I’m not convinced it’s entirely accurate. Jack’s faction is shown as reckless, mercurial and belligerent, but that’s as much a reflection of the character of the man as anything. The other side of the coin is presented by Marisa Pavan and Anthony Caruso as the siblings who favor reaching some kind of accommodation. What’s more, the whole point of the story, as I see it at least, is the that the drive for peace between two implacable forces is never going to be an easy process and it’s difficult to convey such a message without emphasizing warlike tendencies. Admittedly, Jack’s Modocs do appear more violent and their grievances receive precious little attention while the inherent prejudice and shortsightedness of the other side is mainly confined to Robert Keith’s hot headed character. What Daves does eschew is piety and self-righteousness. The character of the easterner Dr Thomas is portrayed as pompous, priggish and ultimately ineffectual, while the preacher who attends Jack in his cell at the end is given short shrift.

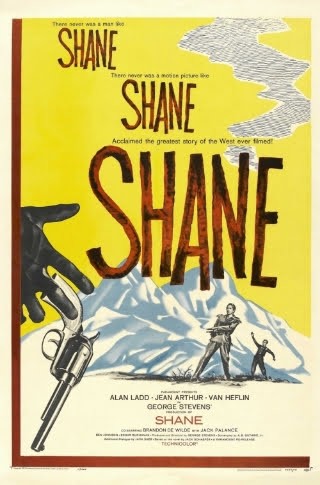

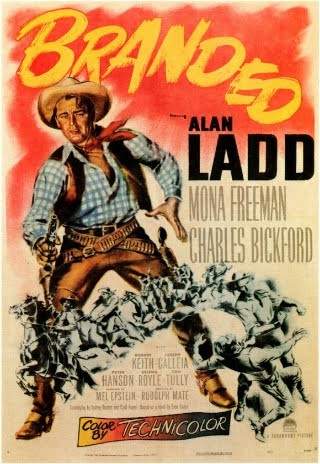

What then can we say about the actors? Alan Ladd had just made one of the great westerns in Shane and his career was at its peak. For all that, his performance here is decidedly subdued, not just the usual quiet understatement he often brought to the screen, but a calm detachment that seems overdone. I get that his character is a man who has had to rein in his emotional reactions in order to fulfill the mission he’s been handed, but all the provocation, tragedy and bubbling passions that are erupting around him arguably call for a more dynamic response. Charles Bronson fares better in a showy part as the Modoc warlord, strutting and powerful and with a gleam in his eye. It’s an entertaining turn, but there’s not a lot of nuance to it. Daves typically got good results from the female cast members and I think Marisa Pavan in particular comes across well in her selfless devotion to Ladd’s character. I find it pleasing that Pavan (the twin sister of Pier Angeli) is still with us and I hope to feature more of her work here – The Midnight Story is a film I plan to get round to in the (hopefully) not too distant future. Happily, Dubliner Audrey Dalton is another screen veteran who is still going strong. She represented the other point in the romantic triangle alongside Pavan and Ladd, although I don’t feel that whole subplot really plays out in an especially compelling way. That coolness and distance displayed by Ladd does it no favors. As for support, we’re somewhat spoiled with a long list of names drifting in and out including Warner Anderson, Rodolfo Acosta, Elisha Cook Jr, Frank Ferguson, Willis Bouchey, Robert Keith, Isabel Jewell and more.

Drum Beat was impossible to see in its correct ‘Scope ratio for a long time until it came out via the Warner Archive. I’ve not yet seen a movie by Daves that I dislike, and most of them are films I unreservedly love. However, Drum Beat is a bit disappointing, not least when it is set beside the towering achievements of his other westerns. It looks beautiful in places and it has that intuitive feel for the Old West that one expects. Still, his trademark sensitivity only appears sporadically, not surprisingly most evident in those scenes where his female characters are prominent – Pavan’s sacrifice and its aftermath, the dignity and regard she and Dalton extend to each other, Isabel Jewell’s cameo, and so on. I’d term it a good western for the most part, but only a moderate entry among this director’s credits.