This is a story about building a house. Is that too glib? Perhaps it sounds like it is, but it’s not meant to be. Would it be better if I said it’s about lack of fulfillment? Well, that’s true too; it’s a movie about both, and at heart it’s a movie about people in love. All of these elements converge in Strangers When We Meet (1960), separate and unconnected when they initially come together, just as the title itself suggests, fuse and then diverge again at the close. Still, that climactic separation is not quite as clean or as complete as one might expect – after all, nobody and nothing can remain unchanged and unaffected by their experiences.

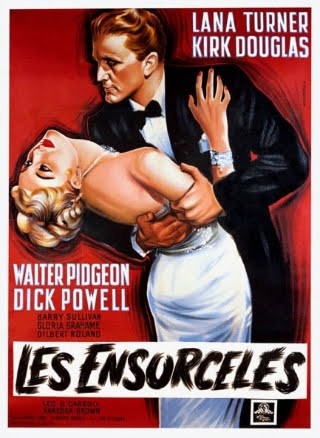

The post-war suburban idyll, that’s the image we’re first presented with. A peaceful and prosperous looking street gradually filling up with chattering parents and children bustling along to the bus stop. They gossip and exchange small talk, bid a temporary farewell to the kids and then start to drift apart again, off to resume their day as the strangers they had been a few minutes before. But not all of them; architect Larry Coe (Kirk Douglas) lets his gaze linger a touch longer on the demure yet voluptuous Maggie Gault (Kim Novak), and she discreetly returns that slow-eyed appraisal. So there we have it, those tiny hairline cracks in the veneer of prim middle-class respectability are suddenly exposed to the glare of the early morning sun. I don’t suppose it’s necessary to go into huge detail regarding the plot here. Suffice to say that Larry and Maggie are both less than satisfied in their lives; she is married to a stiff and undemonstrative man while he feels suffocated by the twin pressure of unrealized professional potential and a wife (Barbara Rush) he blames for stifling his creativity. Therefore, we have two people struggling with what they think are unfulfilled lives, ripe for romance and risk. The trigger for it all, what tips the balance, is the aforementioned house. Larry has been given a commission by a bestselling novelist (Ernie Kovacs) to construct his dream home – something he seizes onto hopefully, as a drowning man will snatch at anything buoyant. It’s this that actually brings Maggie and Larry together, the building of the house proceeds alongside the blossoming of their illicit relationship, with its completion resulting in… Well, watch it yourself and see.

Director Richard Quine had been making a succession of mostly light comedies throughout the 1950s, with a couple of films noir such Pushover and Drive a Crooked Road thrown into the mix. Bearing that in mind, a melodrama in the mold of Douglas Sirk would appear to be an odd project for him to take on. For all that, it works very well indeed, with Quine tackling the serious themes with skill, tact and sensitivity. He never allows it all to become too broad, overheated or overwrought. And visually, he paints from an exciting and evocative palette as he and cinematographer Charles Lang Jr light, frame and color the movie beautifully – from the marvelously tinted and shadowed first “date” for the clandestine lovers to the warm autumnal mellowness of the final scene, and through it all Ms Novak’s costumes progress from brazen scarlet to virginal white later in the movie, indicating a journey back to spiritual purity. All in all, an excellent handling of cinema’s own special syntax.

So to the writing, the solid core of any piece of filmmaking and frequently the area where the most significant strengths or weaknesses lie. In this case it comes from the pen of Blackboard Jungle writer Evan Hunter ( a man I’m more familiar with for his 87th Precinct books under his other pseudonym of Ed McBain) and adapted from his own novel. As I said in the introduction, it’s a movie about building a house and as such needs a firm foundation to anchor it. Indeed the characters themselves comment on a few occasions about the precarious placement of the house, half joking that it may all come crashing down. And here the architect is seen to be really constructing his building for the woman he loves; she appears to have inspired it and even if he’s not fully aware of this himself, I think it ought to be clear enough to the viewer. The tragedy here is that he’s building this for someone else to occupy, which leads back to the accompanying theme of lack of fulfillment – the entire premise of his love can never truly be fulfilled.

Still, it’s not quite as bleak as all that. I can only offer my own interpretation but I think that, ultimately, Hunter wants to put across the idea that the act of loving, both the physical and the emotional, are as close to personal fulfillment as anyone can hope to arrive at. That it may not always be a success or be directed towards the right person is perhaps irrelevant. Some will be lucky, they will connect with that ideal or perfect match, but for others the knowledge that they were able to touch on a form of perfection in an imperfect situation may actually be enough, or at least be enough not to negate that love which was but briefly shared.

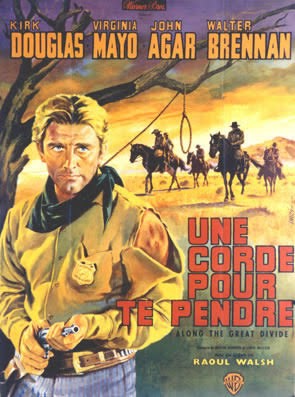

The last time I wrote about a movie starring Kirk Douglas was on the occasion of his 103rd birthday. Since then he has sadly left us but in doing so he also left behind a wonderful legacy of performances to be enjoyed. He was of course a front line star, a man who seemed as big as the movies themselves yet versatile enough to be wholly believable in whatever role he took on. As an increasingly embittered middle-class man drifting into dissatisfied middle age, he’s never less than credible.

There’s a nice degree of subtlety involved in Douglas’ differing interactions with both Barbara Rush and Kim Novak, as wife and mistress respectively. Both actresses bring a lot to the movie too, Novak has the bigger role with more screen time and she uses that enigmatic quality to good effect – incidentally, this was the third of four films she made for Quine – and the hesitancy and uncertainty she tapped into so well in Hitchcock’s Vertigo is in evidence again. Rush has to wait till the third act to get her big moments and handles them just fine, notably the creepy confrontation with Walter Matthau’s two-faced neighbor. Matthau himself is delightfully sleazy and oily in his role, taunting Douglas during the pivotal barbecue scene before later making his move on Rush in the literally tempestuous climax. A word also for Ernie Kovacs, someone else who was used on a number of occasions by Quine. There are only hints at his quirky comedic side as he gives us an interesting take on the self-doubting writer, a successful man who is every bit as much in search of fulfillment, primarily the artistic kind in his case, as any of the other characters. The fact is that pretty much everyone in the movie is living their own variation on the American Dream; the problem is it’s giving most of them sleepless nights.

I’m not sure if Strangers When We Meet has been released on Blu-ray – someone will no doubt set me straight on that – but it is freely available in multiple locations on DVD. I’ve had the Italian release for some time but only recently got around to it, and I’m very pleased that I did. The movie has, to my eyes anyway, been presented very well and the marvelous Scope image is highly immersive. The fact is of course that the story itself draws you in with its touching and deeply affecting portrayal of lost people searching desperately for meaning, fulfillment and genuine love. It really is a rich, layered and intelligent piece of filmmaking, a joy to watch and one I’ll most certainly be revisiting.