La Revolución is like a great love affair. In the beginning, she is a goddess. A holy cause. But, every love affair has a terrible enemy: time. We see her as she is. La Revolución is not a goddess but a whore. She was never pure, never saintly, never perfect. And we run away, find another lover, another cause. Quick, sordid affairs. Lust, but no love. Passion, but no compassion. Without love, without a cause, we are nothing! We stay because we believe. We leave because we are disillusioned. We come back because we are lost. We die because we are committed.

Random musings on the nature of revolution, words which have an attractive feel, a weary patina lying somewhere just the right side of cynicism. That, I think, is the effect they are meant to convey, but therein is their problem, and by extension part of the problem of the movie they appear in. Hearing them spoken by Jack Palance’s wounded rebel and reading them back here leaves me with the impression that they have been crafted for just that, for effect rather than for truth or out of any real conviction. I watched The Professionals (1966) again the other day, a movie I’ve seen fair few times now, and came away from it thinking it entertaining enough although somewhat lacking in substance. Like so many films by Richard Brooks, it doesn’t do much wrong, doing a lot right in fact, yet never actually amounts to as much as the filmmaker would have us believe.

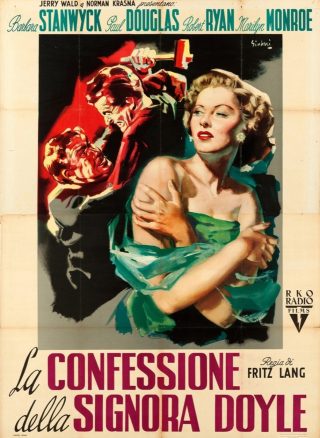

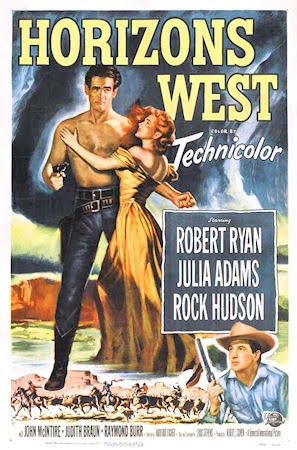

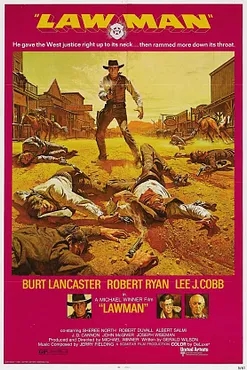

During the latter half of the Mexican Revolution a group of four men, introduced via brief sketches during the opening credits, are hired by a wealthy businessman to get his kidnapped wife back. That’s the plot of the movie in a nutshell. It’s a simple enough setup, fleshed out by the colorful nature of a some of the leads as well as the dynamic created by their intertwined pasts, and of course the turbulent background of a country riven by internal conflict. The hired hands are led by Rico Fardan (Lee Marvin) a former associate of Pancho Villa, Bill Dolworth (Burt Lancaster) a womanizing rogue with a talent for blowing things up, Ehrengard (Robert Ryan) a diffident wrangler, and Jake (Woody Strode) a tracker and expert with a longbow. Their employer is one J W Grant (Ralph Bellamy), an ageing tycoon married to the much younger Maria (Claudia Cardinale). On the other side is Raza (Jack Palance), one of those bandits with a reputation approaching legendary status. The story is broken into a classic three act structure – the preparation and the journey out, the rescue, and the ride back leading to the denouement. If it sounds a bit formulaic, that’s because it is. There aren’t really too many surprises and the twist that is supposed to grab the viewer comes as more of a shock to the characters on screen.

This probably sounds more negative than I mean it to – the film is (as one would hope from the title) all very professionally shot and put together. It’s amiable and exciting in all the right places, the big set piece assault on Raza’s hacienda is filmed with style, the dialogue is peppered with memorable one-liners, and Conrad Hall photographs the desert locations beautifully. Yet when it all wraps up and the final credits roll, I can’t help feeling I’ve just had the cinematic equivalent of an attractively packaged fast food meal – pleasing and enjoyable while it’s there in front of you, but not something that is going to linger long in the memory when it’s finished.

A film scripted and directed by Richard Brooks (The Last Hunt) from a novel by Frank O’Rourke (The Bravados) inevitably raises expectations given the examples of the author’s and the director’s work cited. I guess that’s why it belongs in my own personal category of movies I like and enjoy even though I don’t believe they warrant an especially high rating. Films such as The Last Hunt and The Bravados stay with you long after they have been viewed, the performances and themes, the images and the very philosophy underpinning them have a way of boring into one’s consciousness and commanding attention. I guess what it comes down to is this – those are movies which touch on greatness, The Professionals is fun.

Lee Marvin and Jack Palance appeared in, by my count, four movies together – in additions to this, there’s Attack, I Died a Thousand Times and Monte Walsh. I feel confident that the latter is by far the best of them, closely followed by Aldrich’s intense study of men in war. The fact is all of the star players, and I’m counting Lancaster, Ryan, Cardinale, Strode and Bellamy here, all made much stronger films, all had roles that stretched them and highlighted their strengths to a greater degree than this. On the other hand, every one of these people are in essence playing types in The Professionals. This is not to say their performances are poor or weak, merely that the way the roles are written allow for next to no development – there are hints of back stories, mentions of experiences that would shape characters, but none of those characters grow over the course of the story. What we see at the start is pretty much the same as what we see at the end.

So, is The Professionals a good movie? The critics seem to have been kind over the years and its reputation remains strong. I like it well enough myself; I’ve watched it a number of times and I’m not in the habit of doing so with films which hold no appeal. Even so, I retain reservations about it, which I think is representative of my attitude to or how I respond to much of Richard Brooks’ work. Parts of his oeuvre hit the mark, have an impact beyond the immediate and provoke me in some way. On the other hand, all too often I find I’m left only half satisfied.