Otto Preminger’s Where the Sidewalk Ends (1950) has the feel of something that might have been cooked up had Cornell Woolrich and William P McGivern ever decided to collaborate on a story. There is that quality of the inescapable nightmare, a fatalistic vortex relentlessly dragging the protagonist down, while he is one of those big city cops who appears to be as uncomfortable in his own skin as he is in the department he works for. The end result is a form of psychological trial by ordeal, where the moral fiber of a man is measured by his ability to meet the challenge laid down by his own past.

Right from the beginning it is clear that Mark Dixon (Dana Andrews) is a man in trouble. The patience of his superiors in the police department with his brutal, two-fisted approach to the job is wearing perilously thin. What is perhaps more dangerous though is his appraisal of himself. It’s not voiced yet the truculence that pervades features, manner and posture clearly announces a deep-rooted dissatisfaction. With a final warning still ringing in his ears, he sets out to investigate the death of a rich out of town businessman. The victim ought to have been the mark in a rigged game of dice, but a bit of bad luck on the part of the mobsters running the racket leads to a misunderstanding, which leads to a scuffle, which leads to a murder. So Dixon is one of the bulls sent to investigate and is soon on the trail of the man being lined up as fall guy for the killing. Seeing as this is a story that is full to the brim with ill fortune and bad judgement calls, it is somehow inevitable that a man with a hair trigger temper such as Dixon is going to get into deeper strife when he finds himself alone with an antagonistic suspect. That’s exactly what happens, blows are traded and the suspect, a war veteran with a metal plate in his head, winds up dead on the floor. And it’s here that everything begins to spiral completely out of control. Shocked and panicked, Dixon attempts to cover up the accidental killing, but once he sets the ball rolling the momentum generated threatens to crush everything and everyone in its path, not least the dead man’s father-in-law.

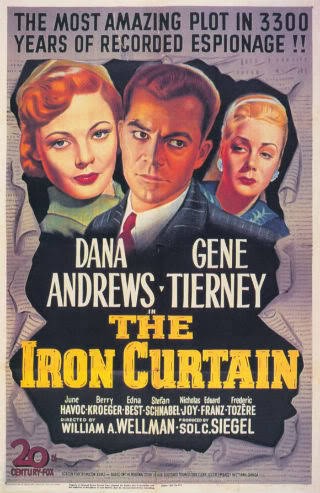

The entire business is further complicated by the fact Dixon finds himself falling in love with the estranged wife (Gene Tierney) of the man he’s just killed. What follows is a variation on that noir trope of a man investigating a killing he is responsible for, the hunter essentially hunting himself. The personal angle and the need to see that blame is not wrongly placed on an innocent man adds some spice, as does the fact Dixon is all the time fighting an internal battle borne of the fact his own father was a career criminal. It sets up an intriguing study of the concept of justice and how it may be best achieved, as well as looking at the potential for attaining personal and professional redemption.

Where the Sidewalk Ends feels like something of a watershed movie. That whistling intro with the opening bars of Alfred Newman’s Street Scene playing over credits chalked on the sidewalk, suggestive of the casual impermanence of a crime scene and the expedience of the methods used to mark it out, as anonymous citizens stroll past seems apt given the way film noir – that genre that wasn’t even aware of its own name at the time – was moving along into other areas. As the new decade went on noir would move gradually away from those tales of personal misfortune and shift its focus onto wider societal ills, organized crime and institutional corruption. The director too would soon be on his way, leaving behind the restraints imposed by being under contract to a major studio.

Recently, after revisiting Preminger’s Anatomy of a Murder I was watching one of the supplements on the Criterion Blu-ray where Foster Hirsch was commenting on the directors insistence on shooting that movie on authentic Michigan locations. Some of that fondness for using real locations comes through in Where the Sidewalk Ends too with much of the film shot on familiar Fox studio sets, but also taking the cameras out onto the streets of New York where possible to give it an air of genuine urban grit. The whole picture has a strong noir aesthetic, canted angles, telling close-ups, characters clustered in tight, claustrophobic spaces framed by doorways and windows, and plenty of shadows carefully lit and photographed by Joseph LaShelle.

Where the Sidewalk Ends was the fourth of five films Dana Andrews would make with Preminger. All of their collaborations are interesting and there’s not a bad movie among them. Andrews has always been a favorite of mine whatever genre he happened to be working in and I’m sure I’ve spoken before of that marvelous internalized style he used so effectively on so many occasions. The part of Mark Dixon allowed him to tap into that: his rage and hunger for violence barely contained every time he encounters Gary Merrill’s conceited gangster, the appalled horror at what he has done when he realizes the murder suspect is lying dead before him, and then the sickening, sliding sensation as he witnesses the net cast by the law drawing tighter around those who least deserve it. These are all different emotions and reactions yet all of them are perfectly conveyed with great subtlety and quietness by Andrews – superb screen acting. Gene Tierney was another veteran of Preminger’s movies, making four in total for the director over the years. One might say her character isn’t as directly involved in the story yet her presence is one of the primary drivers of the plot – the initial killing stemmed partially from her attendance at the dice game, her father called on her abusive ex and placed himself at the scene of the crime as a result of what happened to her, and Dixon’s journey back from the brink towards redemption could not take place without her.

Gary Merrill is good enough in the role of the villain, although he is off screen quite a bit. In a sense though, one could argue that Merrill is not the main villain, that honor belonging to Dixon’s father, the ghost of a long dead hoodlum haunting his son’s conscience and putting a hex on his character. An uncredited Neville Brand makes for a memorable sidekick, superficially tough but easy to crack under pressure. That pressure is applied not only by Andrews but also by Karl Malden as the newly appointed lieutenant who is keen to make a quick arrest. As Tierney’s cab driver father, and Malden’s prime suspect, Tom Tully is hugely endearing. Both Tully’s playing and Tierney’s devotion to him lend credibility to the conflict which assails Andrews as the plot unfolds. All of the supporting actors turn in good work, including Bert Freed, Craig Stevens and Ruth Donnelly. I want to add a brief word too for Grayce Mills, who only appears in one scene. Many of these studio productions contained seemingly throwaway moments, little vignettes that are easily overlooked yet frequently stick in the memory. Such is the case with the old widow living the basement below the apartment where Andrews runs into trouble – there is something touching and memorable about this old lady’s few telling lines about the insignificance of time to the aged, and how she sleeps in the parlor with the radio softly playing to assuage her loneliness.

Some years ago the Bfi released a Blu-ray set of three Otto Preminger films noir comprising Where the Sidewalk Ends, Whirlpool and Fallen Angel, but it now seems to have gone out of print. Anyone fortunate enough to have picked that set up will know that this movie (and the other two titles) looks exceptionally good so it’s worth keeping an eye out should it be reissued, or if a competitively priced used copy pops up.

So, this year ends with Where the Sidewalk Ends. My thanks to all of you who came along for the ride, and I hope I’ll be seeing you again in 2023.