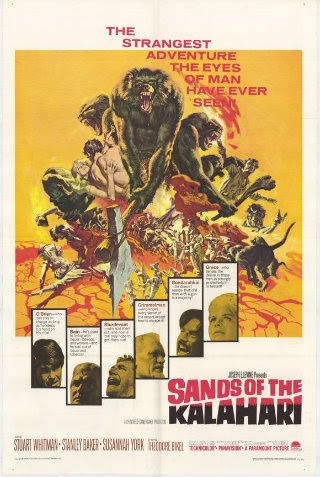

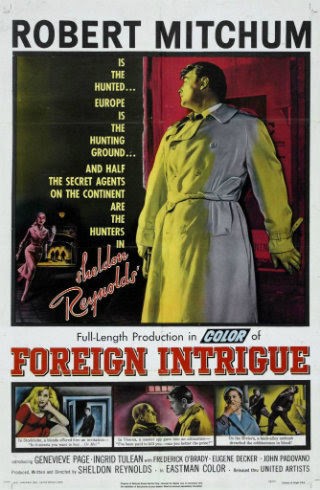

When television was still in its infancy, and for quite some time afterwards, it was quite common to see the appearance of small screen shows inspired by their big screen cousins. Today it seems like a reversal of that trend has taken place with a fair number of big budget productions hitting the cinema that have spun off from TV series. This phenomenon was noticeable in the 1970s when British TV shows frequently found themselves becoming movie features. However, even as far back as the 50s this was not unheard of, though it tended to be less pronounced in Hollywood. One early example of the US studios raiding their rival medium to produce a feature film is Foreign Intrigue (1956). I’ve never seen the TV show but I understand the movie isn’t really an adaptation in the strict sense of the word – it borrows the title and general concept, but that’s about it.

The movie opens on the French Riviera, with a man sauntering round the beautiful grounds of his equally beautiful villa. As he passes into his library and begins to browse the bookshelves, he’s struck down by a massive heart attack. The man is Victor Danemore and the first person to come upon him as he draws his dying breath is Dave Bishop (Robert Mitchum), his publicist. It’s soon revealed that Danemore was a genuine mystery man, one of those characters that could really only be a product of the 50s. Bishop was hired to fabricate an identity for his enigmatic employer and he knows no more about him than the inventions he’s been feeding the outside world. One would think the dead man’s young widow, Dominique (Genevieve Page), could fill in a few gaps but no, she knows nothing of the years before her marriage. So Bishop takes it upon himself to delve into Danemore’s past, to find out who this man was and why a Viennese lawyer is seeking confirmation of the circumstances surrounding his death. The quest moves from France to Austria and then on to Sweden, with Bishop encountering a variety of shady characters and dangerous situations as he tries to piece together Danemore’s fractured history. As he chases the shadows of the past down the murky, cobbled alleys of post-war Europe, a picture begins to emerge. The tale involves murder, blackmail, Nazis and collaborators, and how a legacy of treachery can poison the futures of the unsuspecting. Foreign Intrigue is a film that is very much of its time, sharing some of the characteristics of The Third Man and Mr Arkadin, yet never attaining the levels of suspense or artistry of either. There are some nicely crafted set pieces and atmospheric moments but the end result isn’t entirely satisfying. In short, the build-up promises much more than the pay-off can hope to deliver.

Foreign Intrigue was brought to the screen by Sheldon Reynolds – he wrote, directed and produced the movie – after Robert Mitchum expressed an interest in working with him. Reynolds had had some success with his TV show of the same name, and hastily knocked out a script. As I understand it, a good deal of the appeal of the show was its use of authentic European locations, and the movie employs the same tactics. This aspect is probably the greatest strength of the film, lending it an air of glamour and reality that even the most lavish studio mock-ups couldn’t hope to achieve. Leafing through Lee Server’s biography of Mitchum certainly gives the impression that the movie was an enjoyable one to make, and the star seems to have had a good time hopping around Europe. Reynolds and cameraman Bertil Palmgren compose some very attractive images and create atmosphere and suspense here and there, but the script fails to provide adequate backup. There’s too much shallow characterization to generate real interest in the people involved, and there are too many plot holes and unresolved questions. Even the finish is weak, its open-ended quality betraying Reynolds’ television background – it actually comes off like a pilot where the groundwork is being laid for the forthcoming episode.

Mitchum was the biggest name in the film and the whole thing revolves around his star power. While this could never be counted among his better roles, he’s good enough in the part. His trademark nonchalance is used well and he handles the thick-ear moments with the kind of toughness that makes it feel believable. Amid all the shadowy cloak and dagger stuff, he gets involved in two romantic sub-plots, but I didn’t feel either of these worked especially well. The two females in question, Genevieve Page and Ingrid Thulin (here billed as Ingrid Tulean), certainly look attractive yet the performances are just passable. Page is poorly served by a role that’s seriously underwritten and underdeveloped, while Thulin simply appears uncomfortable and unsure – disappointing when you consider her later success with Ingmar Bergman. However, there’s some fine support offered by Frédéric O’Brady as the double-dealing foil to Mitchum. A quick look at O’Brady’s IMDB entry reveals the man led a life that could comfortably be described as quirky, fascinating and off-beat. A good deal of this unpredictable quality shines through in his performance and some of the film’s best moments occur when Mitchum and he share the screen.

Foreign Intrigue is a film that I’d never had the opportunity to view until recently. It was one of those titles that you see included in filmographies and wonder what it’s like. Being a United Artists production, it’s part of the MGM library and recent arrangement with TGG Direct has seen it making its DVD debut. The movie is presented in anamorphic widescreen I’d describe it as typical of many MGM releases we’ve seen down the years. I mean that the transfer is about medium, some dirt and speckles, fair enough colour and no visible restoration. There are no extra features whatsoever and the movie shares disc space with an non-anamorphic version of The Quiet American. However, the fact that the title has been made available at last, and the very attractive price, should be taken into consideration. All in all, I found Foreign Intrigue to be a reasonably pleasant, if unremarkable, way of passing the time. The movie isn’t anything special and, realistically, will probably appeal mainly to Mitchum completists like myself. Still, bearing in mind how cheap the DVD is, it’s worth a look at least.