Another modern western, and another message film. Man in the Shadow (1957) treads a similar path to Bad Day at Black Rock by having a lone individual take a stand against a racially motivated murder. The main difference is that this time the hero is not an outsider who’s swooped down on an alien world seeking justice. In this movie our protagonist is a familiar face in his small community but whose sense of personal and professional honour bring him into direct conflict with with those he’s known all his life.

Ben Sadler (Jeff Chandler) is the sheriff of a sleepy western town. The routine and mundane nature of his job is highlighted early on when he opens up the cells to release the town drunk who’s been sleeping off a heavy one. He hands him a stern warning, which we know is really only for show, and then bids the old timer good day. That’s the kind of town we’re in – one where crime is generally confined to manageable, petty affairs that tend not to represent a major threat to the community. Within moments however, a much more serious matter is to be laid before Sadler, one which is not only reprehensible in itself but also, as a result of what any investigation will entail, poses a threat to the finances and, by extension, the very viability of this small backwater. Sitting huddled and almost forgotten in the office is an old Mexican with a story to tell that’s about to present the sheriff with a moral and professional dilemma. The old man has witnessed the murder of a young friend by two cowboys at a nearby ranch. He doesn’t really expect anyone to take his tale seriously, partly because of his lowly immigrant status and partly due to the identity of his employer. Virgil Renchler (Orson Welles) is a big man, both physically and financially, and his ranch is the life blood of the town. Without the patronage of his sprawling ranch the businesses would quickly wither and even the railroad stop might fall into disuse. Sadler is aware of the clout wielded by Renchler but, unlike his slovenly and skulking deputy, he’s also conscious of his duties as the representative of the law. So, it’s with some reluctance that he gives his word to the old man and begins to tentatively look into the allegations. Renchler, though, is a throwback to the old cattle barons, a man whose self-sufficiency and power has led him to believe in his own infallibility. When he tells Sadler that he has no business asking questions of him and dismisses the killing as nothing more than an insignificance, the sheriff’s indignation is aroused. Thus we have one of those perennial western themes, the clash between the laws of civilization and the moneyed big shots who see themselves as being above such naive concerns. The thing is though that Sadler isn’t merely up against a powerful rancher, the influence and fear that Renchler inspires in the country is such that virtually the entire population of the town turns against their lawman. Sadler’s only allies are Renchler’s disgruntled daughter, Skippy (Colleen Miller), and the Italian immigrant barber – not exactly a pair of heavy hitters. Still, in spite of the enmity of his former friends, an attempt on his life and a public humiliation, Sadler presses ahead with the investigation that nobody wants.

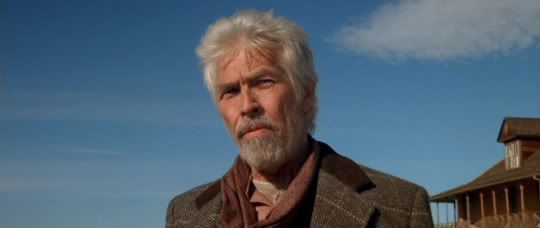

Although the racism implicit in the murder is acknowledged and explored, that’s not the real issue of the movie. The primary concern is the corrupting influence of business and how entire communities can be effectively blackmailed into abandoning their awareness of right and wrong for the sake of financial gain. While this moral issue remains at the forefront throughout, Jack Arnold’s direction ensures that it’s conveyed dramatically rather than by means of noble speeches and the like. The pace is brisk and the development direct so there’s not much room for complex characterisation; we know where we stand as regards the principals right from the beginning and that doesn’t change much by the close. Welles does manage to elicit some slight sympathy as the man whose blustering independence has painted himself into a corner. That’s one of the things about Welles as an actor – even when he played villains it was hard not to feel a little for him. He does lay it on a little thick at times, but complaining about Welles’ tendency to ham it up is akin to decrying John Wayne for his machismo – it’s part of the package and you know that when you go in. Jeff Chandler is pretty good too as the isolated sheriff who knows full well that he’s probably biting off more than he can chew, but whose own personal code precludes his backing down. The main weakness lies in the script, not that it’s poorly executed but that it’s themes are too familiar. There’s nothing especially new or groundbreaking in the plot and although it’s carried off professionally there is a certain unavoidable staleness to it all.

Man in the Shadow is available on DVD from a number of sources: from Germany, France and a recent DVD-R from Universal in the US. I have the German release from Koch Media and it’s a very nice presentation. The movie is in anamorphic scope with very crisp black and white images and obviously came from a clean, strong print. There are no forced subtitles on the English track and there are some attractive extras too. Apart from the trailer and gallery, there’s a 14 minute interview with Jack Arnold where he talks about his memories of working within the studio system and the changes in filmmaking he observed down the years. The movie is an entertaining and pacy one that has a point to make. I found the performances and direction all up to scratch, and the only problem was the lack of originality in the story. Still, it’s not a bad way to spend an hour and a quarter or so – and anything that involves Orson Welles’ participation has to be considered worthwhile.