Most people are aware that revisiting a movie can be either a rewarding or a disappointing experience. For myself, subsequent viewings have more often than not proved to be positive. That may say something about me, or it may be a result of the kind of movies I tend to gravitate towards. Phantom Lady (1944) was a film I’d seen a good few years ago and one which, at the time, I thought was OK but nothing special. Anyway, having recently bought the DVD I decided to give it another go. I thought it was fantastic, like watching a completely different film – everything just seemed to click into place. I have a hunch that a large part of the reason behind this reappraisal is due to the use of one major plot device which bugged me on my first viewing. Naturally, I knew what was coming this time around, so it didn’t bother me in the least – in fact, I found it to be one of the film’s better ideas and, lo and behold, the whole thing worked for me.

The film begins much like a standard murder mystery. Scott Henderson (Alan Curtis) is an engineer with marital problems. After an argument with his wife he heads to a bar to drown his sorrows, and finds himself seated next to a woman with a big hat and her own troubles. Since he’s got a couple of theatre tickets and nothing better to do, he takes her along to the show. The lady in question sets just one condition – no names and no details. At the end of the night the two of them bid each other farewell, and that ought to be the end of that. However, on returning home Henderson finds his wife murdered and the police anxious to learn how he’s spent his evening. The woman who could furnish him with an alibi would seem to be an easy one to trace, after all she had drawn the attention of a number of people. But no, no-one remembers her, or if they do they’re not saying. So Henderson is tried and convicted of murder. Just when all seems lost, however, Henderson gets a lifeline. His loyal secretary (Ella Raines), his best friend (Franchot Tone) and a sympathetic cop (Thomas Gomez) take it upon themselves to try and find the mysterious Phantom Lady.

The idea of an innocent man pitched into a nightmare world where no-one believes him is a staple of noir, and Phantom Lady has an excellent pedigree as it originates from the pen of Cornell Woolrich (although this novel was written under his William Irish pseudonym). The plot device which I alluded to above is the revelation of the killer’s identity about halfway into the film. This has the effect of transforming the story from a straightforward mystery into a taut suspense picture, and it’s all the better for it. Since the viewer now knows more than the characters do, he is free to concentrate on other aspects of the film – and there’s much to admire here. The lengthy sequence where Kansas (Raines) mercilessly stalks a tight-lipped bartender is masterfully shot. From the long shot of her mask-like countenance staring at him down the length of the bar, along the slick and rainy sidewalks, on a deserted platform, to his final demise under the wheels of a truck, you can feel the tension rise and the man’s fear become palpable. This neatly reverses the roles one expects to see in a movie of this vintage, and has the effect of putting a fresh spin on a potentially trite situation. In fact, Phantom Lady is ahead of its time in a number of ways, not least the atmosphere of sexual tension it creates. Another memorable scene takes place in a back street jazz club, where a bunch of stoned and liquored up musicians do a little after hours improvisation. The edge here comes from the sight of Kansas, looking cheap and provocative, driving an ill-fated drummer (professional squirt Elisha Cook Jr) half crazy with lust. The close-up of the expression on his face as his drumming grows more and more frenzied is pure gold, and must have raised a few eyebrows at the Hays Office.

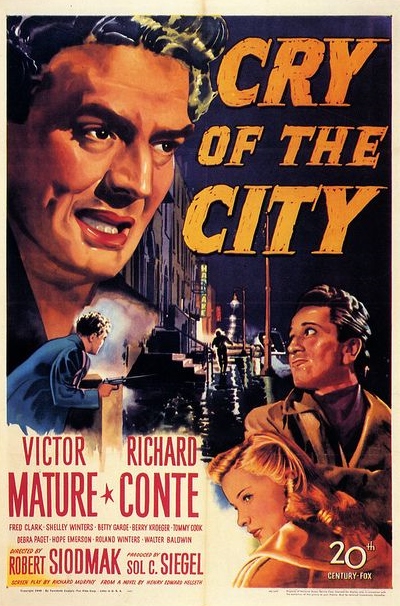

Despite being billed second, the real star of the show is Ella Raines. Her part as Kansas (at the time it was a kind of fashion to hand nicknames to female leads in movies: Lauren Bacall becoming Slim in To Have and Have Not and Lizabeth Scott in Dead Reckoning getting saddled with Mike!) is the most substantial one in the movie and offered her ample opportunity to show what she could do. I’ve already mentioned a couple of scenes above but she holds the attention throughout, displaying a tough, almost masculine, determination without ever being anything less than a woman. Franchot Tone, who received star billing, does well enough even though the nature of his role was one that encouraged a touch of overacting. Alan Curtis generally gets overlooked or dismissed by critics of the film, but I feel that’s a little unfair as he doesn’t get the opportunity to do much in the second half. When he is on screen he performs capably and believably enough – he’s no standout but he is acceptable. Thomas Gomez and Elisha Cook Jr were fine character players in many films and their presence adds some more class to proceedings. Phantom Lady was Robert Siodmak’s first in a series of excellent noir pictures throughout the 40s. All of his films made fine use of atmosphere, imagery and lighting, and this was no exception. There are countless examples I could cite, including the weird, tortured sculptures dotted around the killer’s apartment. However, aside from those already mentioned, there’s a marvellously shot scene where the killer lectures one of his victims on the ways a man can use his hands for both good and evil. As he talks the camera concentrates on his own hands, picked out stark white by a spot, while the man himself blends into the background shadows.

For some reason Phantom Lady has yet to be given a DVD release in R1 by Universal. However, it is readily available in R2 (France & Spain) and R4 and, although I can’t be sure of this, I have a feeling all these versions are sourced from the same print. I watched the R4 from Aztec (licensed from Universal) and the transfer is a good one. There hasn’t been any work done on it, evidenced by the presence of some scratches and speckles and a fine vertical line that appears on the right of the screen at one point for six minutes or so, but it is very sharp and has strong contrast. The R4 comes on a barebones, single layered disc but the relatively short running time means it doesn’t appear to be over-compressed. I don’t believe I’ve seen a poor film noir from Robert Siodmak yet and my repeat viewing of Phantom Lady has elevated its value in my opinion. This is a movie I can see myself returning to fairly often and I would certainly recommend any noir fans pick up a copy.

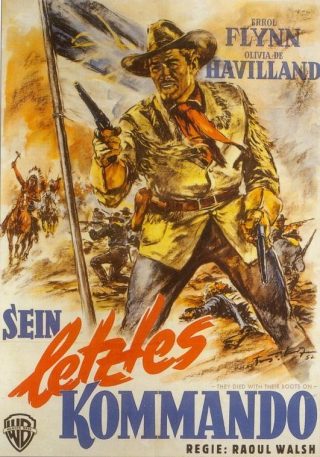

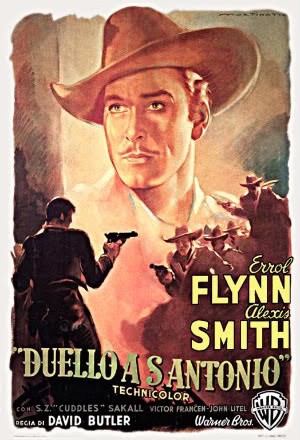

It’s often difficult to put your finger on exactly why a film doesn’t work for you. I’ve frequently found that such films suffer from two basic flaws; they can’t seem to make up their minds what style to adopt, and/or the director is someone who has no real affinity or feel for the genre in which he’s working. The existence of one of these factors can easily hamstring a production – when they appear in tandem it’s never good news. I feel that San Antonio (1945) is one of those films that falls into this unfortunate category. There’s actually the makings of a fine film in there, and indeed it contains some well executed sequences, but it ultimately loses its way and winds up as a pretty unsatisfactory experience.

It’s often difficult to put your finger on exactly why a film doesn’t work for you. I’ve frequently found that such films suffer from two basic flaws; they can’t seem to make up their minds what style to adopt, and/or the director is someone who has no real affinity or feel for the genre in which he’s working. The existence of one of these factors can easily hamstring a production – when they appear in tandem it’s never good news. I feel that San Antonio (1945) is one of those films that falls into this unfortunate category. There’s actually the makings of a fine film in there, and indeed it contains some well executed sequences, but it ultimately loses its way and winds up as a pretty unsatisfactory experience.