After contributing a number of write-ups encompassing film noir and a couple of visits to the small screen, guest poster Gordon Gates has turned his attention to a late ’50s western with Dale Robertson in the lead and Paul Landres behind the camera.

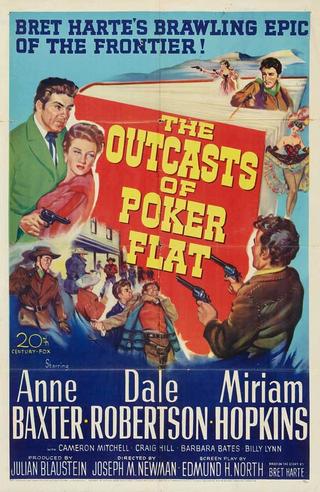

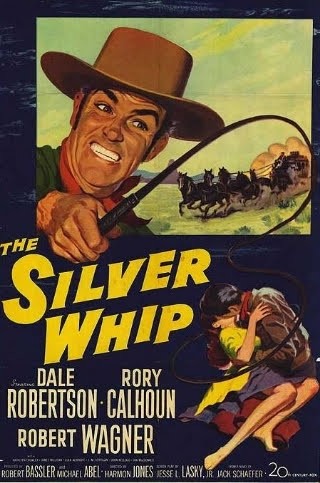

One of the more popular western stars of the 1950’s was, Dale Robertson. He starred in a string of well made dusters like, The Silver Whip, City of Bad Men, Dakota Incident, A Day of Fury and Sitting Bull. He was also the star of the popular western television series, Tales of Wells Fargo which ran for 201 episodes between 1957 and 1962. Here is a lesser known Robertson film, Hell Canyon Outlaws (1957)

This one is an interesting low budget film from Jarod Zukor Productions and released by Republic Pictures. The leads are played by Dale Robertson and Brian Keith.

This one is set in the small western burg of Gold Ridge. Dale Robertson is the town Sheriff, who along with his Deputy, Charles Fredericks, has cleaned up the former rough and tumble town. It has been a few years since there was any real trouble and the town council now decides to let Robertson and company go.

Of course this idea soon backfires as four hard and ready types ride into town. The group is led by Brian Keith, and include three of the biggest thugs to grace the screen. The 6’7″ Buddy Baer, the 6’5′ Mike Lane and the 6’6″ Don Megowan, who make for a most imposing gang.

The outlaws soon make themselves at home, tossing hotel residents out of their rooms, helping themselves to the saloon’s beverages and so on. The whole thing rubs former Lawman, Robertson, the wrong way, but he can do nothing about the swine since he is no longer in power. And, as it so happens, the new Sheriff, Alexander Lockwood, is out of town.

In the mix here is Robertson’s soon to be bride, Rossana Rory. Miss Rory of course wants her man to stay out of the mess. One of the town’s young men, Dick Kallman, who considers himself handy with a gun, goes after the four. This does not go well for Kallman as he is quickly disarmed and tossed into a mud hole face first. He is lucky not to be killed as the outlaw types laugh at him.

The gang plan on having fun before hitting the local bank for a hefty withdrawal. Robertson can see where this is going, and sends his former Deputy, Fredericks, off to retrieve the new Sheriff from out of town.

When the new Lawman, Lockwood returns, he goes to have a talk with Keith and his men. As this is happening, the young Kallman has reamed himself and pops into the saloon to continue his “discussion” with gang leader, Keith. Kallman of course is soon ready for a plot at boot hill. Keith and the boys now slap around Sheriff Lockwood. They decide it is now time to do their “banking business”.

Robertson by now has had enough of this nonsense. Robertson and Fredericks arm up and go a calling on Keith and crew. Outlaw Baer is the first to go down with a bright shiny hole drilled through his forehead. More rounds fly with Megowan and Lane on the wrong end of the exchange.

Soon it is just Keith and Robertson standing across from each other. Keith pulls a 20 dollar gold piece from his pocket. He tells Robertson he will flip the coin into the air, when it hits the floor, they draw. The coin hits and iron flashes with both getting off a round. Who is the winner?

This one is a decent low budget quickie that runs just 72 minutes. The story is a bit shop worn and plays out like a poor man’s High Noon. Having said that, the cast and crew do quite well with what was an obvious shoestring budget. The acting is acceptable and the look of the film, quite sharp.

Paul Landres handles the direction here. Landres was a long time film editor who took up the directing reins in the early 50’s. While mainly known for television, he did work on a few b-films. The director of photography was the Oscar winning cinematographer, Floyd Crosby. Crosby was the man who shot High Noon. Also helping with the look of the film is another Oscar winner, editor, Elmo Williams. Williams also worked on HIGH NOON and won his Oscar for his efforts on that production.

Rossana Rory some might recall from the Italian films, The Big Boodle and Big Deal on Madonna Street.