“I just want to be somebody… “

Why does film noir continue to resonate? Why does it continue to pull in viewers, beguiled by its shadow drenched nightmares? That is does exert a draw on audiences is beyond question and part of it is maybe down to the look, the attitude, the charm of something at once recognizable yet lost in time. Still, I feel there’s something else at play for film noir is a very human form of filmmaking; it is predicated on the frank acknowledgment of weakness and frailty, perhaps growing out of character flaws, ill fortune, poor choices, or even some unholy trinity of them all. In a way, there is something about the lack of definition regarding film noir that points to its core appeal. There has been decades worth of conversation and controversy over when noir began, when it ended, what it actually is and whether it can even be referred to as a genre. And at the end of it all, there remains no definitive answer, just schools of thought one might subscribe to. As such, is it possible that film noir is in essence a cinematic expression of uncertainty and confusion, mentally, morally and spiritually? Somehow it feels appropriate that the main character of Night and the City (1950) should say those words quoted at the head of this piece, struggling to articulate an ambition that he cannot fully visualize, much less define with clarity.

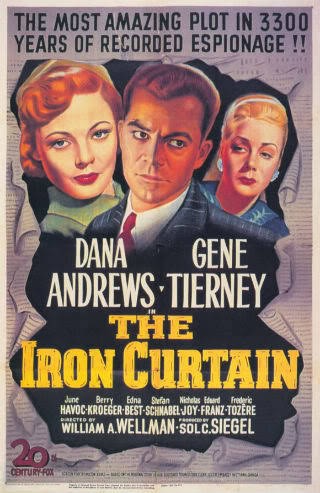

Movement and position matter. Anthony Mann frequently had his characters striving to rise, forging a path upward with mixed results, while Abraham Polonsky famously had John Garfield racing down from the heights. The characters in Jules Dassin’s Night and the City, on the other hand, start off at the bottom and remain resolutely anchored there. In a sense, nothing really changes throughout, at least not as far as Harry Fabian (Richard Widmark) is concerned. The opening and closing sequences see him racing through the streets of a broken post-war London, a grandiose chiseler with danger hot on his heels and the hope of sanctuary and salvation, even if it’s only temporary in nature, awaiting him in the form of Mary Bristol (Gene Tierney).

Harry Fabian is what can only be termed a dark dreamer, immature both emotionally and ethically. Mary loves him, that much is clear, not so much for what he is as what she imagines he could be, and Harry in a way is also in love with that projection of what he dreams he could be. The problem though is that neither Mary nor more importantly Harry himself is quite sure of who or what he might be. He is, as his neighbor observes, an artist without an art. We encounter him first as a strictly small time operator, a tout steering mugs to the clip joint where Mary sings, scratching around in the detritus of a city still partly bewildered in the wake of its wartime pummeling for any scheme that might turn a fast buck. Human nature being what it is, he’s not the first nor will he be the last person with his eye on the quickest way to reach easy street. The problem with this approach to life lies in the fact the route there is typically mined. Thus when Harry happens upon what seems like the perfect opportunity to muscle his way into the world of professional wrestling he fails to anticipate the the traps awaiting him. Blinded by his enthusiasm and unaware of how his smug efforts to play all of his rivals off against each other is actually weaving a Gordian knot of epic proportions, Harry is doomed by his own slickness.

It feels kind of appropriate that Jules Dassin would make Night and the City just as the appalling HUAC episode was reaching its peak. Zanuck had dispatched Dassin to London to shoot the movie where he would be beyond the reach of those congressional committees. By the time the movie was completed, the director was firmly on the blacklist and could no longer take any part in the editing process. Nevertheless, the result is portrait of bleak romanticism, where passion, ambition and duplicity all charge headlong towards an emotional intersection and the resulting collision leaves few survivors standing. I have seen assessments of the movie, both contemporary and subsequent, that lament the dearth of sympathetic characters, citing this aspect as a weakness. Such evaluations leave me wondering if I was watching the same movie. Perhaps it’s just me, but I’ve never seen the need to conflate admirable with sympathetic. I’ll concede that there are few truly admirable figures on show, but that does not mean there are none who are sympathetic. If anything, I would assert that almost all of the principals earn some sympathy.

Widmark’s role is almost as difficult to categorize as film noir itself. Fabian is neither hero nor villain in the proper sense of the words, nor would I be entirely comfortable referring to him as an anti-hero. Right up to the tragic moment which precipitates the climactic hunt, he does some contemptible things as he attempts to plug the leaks suddenly appearing in his plan, but the people he’s deceiving are no saints themselves so it’s hard to condemn him too much for that. As the various threads of his schemes become ever more entangled it’s a bit like watching an accident unfold in slow motion. Aside from his mounting desperation, a few moments such as the early scene in Tierney’s flat where the frustration of both is emphasized, as well as the later exchange with an implacable hotel manager serve to add layers to the character and knock off some of the corners. I don’t believe either Dassin or screenwriter Jo Eisinger had any intention of passing judgment on Fabian and certainly don’t encourage the viewer to do so – he is merely presented as he is. His maneuvering does bring about tragedy, but that occurs indirectly. By the end, when he lies spent and bereft the appearance of Tierney framed in a doorway like some angel of the dawn affords him the opportunity to seek a form of redemption through personal sacrifice. Whatever one may make of the gesture, it does indicate a man who is not merely self-absorbed. What’s more, even though he may be abandoned and betrayed by almost everyone, there’s no getting away from the fact this woman loves him in spite of all his flaws – that in itself places the character on a different level.

That said, Tierney’s part is a relatively small one. Her important scenes bookend the movie and she’s only on screen intermittently in between. It seems that Zanuck was keen to have her in the cast and her role is a pivotal one despite the lack of screen time overall. By humanizing Harry Fabian and adding another dimension to his character, Tierney helps to ground the movie and give it greater emotional depth. The other major female role is that of Googie Withers, the discontented nightclub hostess who is trapped in a relationship for purely financial reasons, something which would not have been uncommon for a woman at the time. Sure she is underhanded and motivated by selfishness, but it’s not so difficult to understand how circumstances have driven her in that direction, nor do I believe it should be so hard to empathize with her efforts to extricate herself from a wholly unsatisfactory marriage. Her husband, played by the oppressively bulky Francis L Sullivan, is another figure who is far from perfect. Insecure despite his clout and dominance in the way such large men often are, he pulls strings and manipulates Harry Fabian like some malign puppeteer out of a desire to see him brought low and in so doing maybe hold onto the woman he so badly needs. It’s a performance that manages to be simultaneously dangerous, vindictive and pitiful.

Many of the other supporting players are portraying characters who are associated in one way or another with the wrestling world. This milieu is appropriate even if it’s not an area that has been extensively featured in film noir – Ralph Nelson’s Requiem for a Heavyweight is the only other notable example that I can think of off hand. Boxing tends to be the go-to sport and I find the choice here a telling one. Boxing might be susceptible to certain abuses, it may attract corruption, but it still retains some inherent nobility, similar to the way Greco-Roman wrestling retains a link to the classicism of the ancient world and something finer. On the other hand, the crass vulgarity of professional wrestling exists on a much lower plane, a true moral wasteland. It’s that very cheapness, that sense of debasement which lies at the heart of Fabian’s flawed scheme and also forms the basis of the conflict between Herbert Lom’s shady underworld promoter and his scrupulously honest and dignified father. It’s highlighted too in the contrast between the easy superiority of that old athlete (Stanislaus Zbyszko) and the barely articulate coarseness of Mike Mazurki’s hulking and murderous pro.

Night and the City had two cuts, the shorter US version, which Dassin seems to have preferred, and a slightly longer British version. The UK Blu-ray from the Bfi, which now appears to be out of print and consequently is rather expensive, offered both cuts – I think the US Criterion also has both versions too though. I don’t know how popular a view this is, but I find I prefer the longer British cut of the film; perhaps the noir credentials are slightly weakened or some might say compromised yet I like the way it shades the character of Harry Fabian in another light. I find it provides another layer of tragedy and thus heightens the ambiguity of the experience. Nevertheless, this is prime film noir regardless of the version one favors and top filmmaking in anyone’s book. Widmark was only about a half dozen or so movies into his career at this point, already in the middle of a remarkable run of performances in very fine films while Dassin had just come off a short streak of excellent films noir. Under the circumstances, it’s hard to see how this one could miss. A first class movie all round.