Don’t worry. Some of the best movies are made by people working together who hate each other’s guts.

Seeing as Kirk Douglas celebrates his 100th birthday today I wanted to make a point of featuring one of his movies to mark the occasion. With one of the great movie stars I figured it would be appropriate to choose a movie about movie-making, not only one of the best of that little sub-genre but one of the best Hollywood has produced. The Bad and the Beautiful (1952) is a carefully crafted piece of work, episodic in structure but with an organic, flowing quality that ensures scenes and sequences segue naturally to provide us with a portrait of a man both shaping and simultaneously being shaped by the cinema. Sounds like a perfect role for Douglas, doesn’t it?

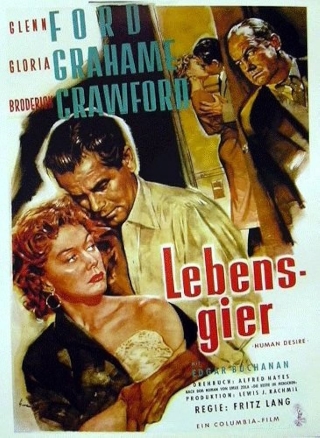

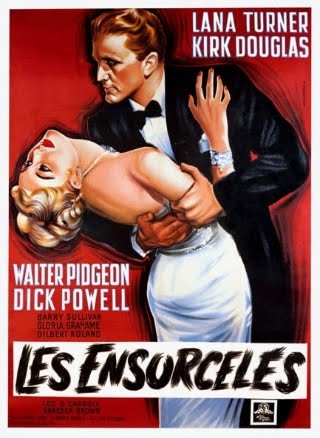

If one wanted to be glib, it could be said the film is the story of a phone call. In fact, it starts with a series of telephone calls, three to be exact and each one is rejected with something approaching relish. Three calls to three Hollywood figures, all of whom take pleasure in telling the party at the other end of the line to take a running jump. That guy at the other end of the line is Jonathan Shields (Kirk Douglas), once a big-time producer but now reduced to hearing casual brush-offs across a long distance line. So we’ve got a good hook right here, you do tend to wonder why a man should be summarily dismissed in this fashion. Curiosity is such that we want to know what a man like this has to say, and by the end of the picture those on the screen clearly share this feeling too. In the meantime, we have the build-up, where studio executive Harry Pebbel (Walter Pidgeon) tries to persuade the director (Barry Sullivan), the leading lady (Lana Turner) & the writer (Dick Powell) to at least take Shields’ call and give their collective answer on whether or not they are prepared to work with him one more time. So, this trio gathers in Pebbel’s office while he, through flashbacks, recalls the way their lives and careers became entwined with that of Shields, and why they feel the way they do about him.

Hollywood thrives on narcissism, it loves to look at itself and can’t resist encouraging us to look at it while it indulges in this introspection. You could say that’s indicative of the all-consuming vanity of the movies, the conviction that audiences will be fascinated by the chance to peek behind the cameras and glimpse the artists and technicians at work and play, that there’s no drama as compelling as the everyday lives of the filmmakers themselves. And I guess they’re right, there’s always been a market for celebrity watching and this has shown no sign of abating any time soon, if anything it’s more intense than ever these days. We sometimes hear about stripping away the glamor but the classic Hollywood exposés didn’t really do that, sure they showed the less savory side of the business and those involved in it but even so they couldn’t help making it look good. As the title of this film suggests, there are some rotten people on screen but they and the world they inhabit remain beautiful and captivating. The Oscar-winning Charles Schnee screenplay focuses on the ruthlessness, the lack of scruples of Shields, the way he’s consistently used and manipulated his colleagues to attain success. Yet, for all that, despite the duplicity and the betrayals, the milieu holds our attention and we’re never allowed to forget that Shields brought success even to those he hurt.

Director Vincente Minnelli clearly enjoyed turning the cameras around since he, and Douglas, would return to the theme 10 years later when they made Two Weeks in Another Town, again scripted by Schnee and produced by John Houseman. He’s always going to be best remembered for his musicals but it has to be said he had a marvelous talent for well-judged melodrama – this movie, the aforementioned Two Weeks in Another Town, Home from the Hill and the dazzling Some Came Running are significant artistic achievements and add up to a highly impressive mini-filmography by themselves.

Kirk Douglas was second billed in The Bad and the Beautiful behind Lana Turner and earned himself his second Oscar nomination. He didn’t win (losing out to Gary Cooper in High Noon that year) and claims in his autobiography to have been surprised by the nomination, believing his roles in Wyler’s Detective Story or Wilder’s Ace in the Hole were more worthy of such an honor. I think this says something about the way Douglas views his own work, seeming to prefer the more driven and less sympathetic parts. While there is much to dislike about Jonathan Shields, it’s said that Minnelli worked on Douglas to bring out the nicer side of the character and tone down the more explosive and less likeable aspects. Which is not to say he doesn’t explode at any point – he does have two fairly intense, in-your-face scenes opposite Lana Turner, but it probably wouldn’t feel like a proper Kirk Douglas film if they weren’t there.

Lana Turner wasn’t an actress who ever impressed me all that much, meaning she was always someone you noticed in a movie (her looks kind of demand that) but whose roles were frequently less memorable, with a few notable exceptions. I think The Bad and the Beautiful ranks as one such exception. The fact she was playing an insecure, alcohol dependent star was an advantage as it required a degree of fragility and vulnerability that Turner was able to convey successfully. In terms of awards though, the big winner among the actresses was Gloria Grahame, who scooped the Oscar for best supporting actress. Grahame was a terrific screen presence, sexy and credible in just about everything I’ve seen her in. Her part in this film is a small one, confined to the section with Dick Powell, yet she doesn’t waste a moment of the time she has. Powell was fine too as her cynical husband, adding an intellectual spin to the kind of insolence he had down pat by this stage. I generally like Barry Sullivan, he was one of those guys who could be a hero or villain (or even something in between) quite effortlessly. He was good enough as the director who sees his idea stolen but it’s an undemanding and perhaps a bit of a thankless part under the circumstances. And there’s plenty of depth in the cast – Walter Pidgeon, Leo G Carroll, Gilbert Roland and Paul Stewart all make contributions.

This is a movie where some people like to see if they can pick which cinema personality each of the main characters was based on – Douglas’ lead appears to be a composite of sorts with the characteristics of at least two producers (one of whom is a cult favorite) on view. Of the others, some are pretty obvious (Lana Turner’s part, for example) while others (like Barry Sullivan) are less so. I won’t go naming any names here – it might spoil a little bit of the fun for some and anyway the curious can easily search online for clues/opinions. That’s just trivial stuff though, the movie provides a masterclass in professionalism and polish where there’s next to nothing to fault in the direction, writing, photography (another Oscar there for Robert Surtees) and acting. The Bad and the Beautiful is an extremely smooth and classy piece of filmmaking, Hollywood writing its own lore and having a good time doing it. The film is easy to find and looks good too, at least my old Warner Brothers DVD does. Viewed for the first or the fiftieth time, it still satisfies.

It’s a rare thing to be able to post something on the occasion of the 100th birthday of a living screen legend, a bona fide star of the Golden Age of cinema, and it gives me a real kick to be able to do so on the day Kirk Douglas hits three figures – congratulations to him and may he see many more.