The daily grind, routine and repetitious. This is something most people can relate to, an integral part of all our lives just as much as sunrise and sunset. What does it represent though? Is it boon or bane? Well it certainly encapsulates the concept of security, and not just in a financial sense. That familiarity, that precise knowledge of where one is going to be at a given hour, perhaps even a given minute, of any day of the calendar offers reassurance. Yet reassurance is necessarily wedded to restrictiveness and at some point the balance between those two points of reference might just start to slip. That’s what happens in Pitfall (1948), a frank analysis of the way post-war suburban security and comfort could start to smother. Everything about it characterizes the classic film noir setup, the slow drift into dissatisfaction, the allure of the forbidden, the unwise choices and the way rapidly snowballing consequences threaten to smash everything in their path.

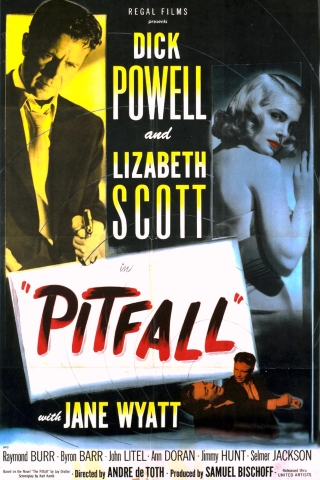

Johnny Forbes (Dick Powell) is a man who ought to be happy with his lot in life. He’s got a devoted wife (Jane Wyatt) and a bright young son. He’s got what appears to be a successful career in insurance and lives in a neat and attractive suburban home. What could be better than waking up to a breakfast that has been prepared and laid out before him, with his family around him, the sun pouring through the window and the promise of another relatively carefree day ahead. That’s how it should be, but the pain of predictability is etched into the hangdog features of Johnny Forbes as he contemplates it all. Both his demeanor and his conversation betray a man ripe for rebellion, a guy who has wearied of respectable averageness, of being part of the backbone of society. Such a man is just a step away from recklessness, he’s practically sleepwalking into peril. A visit to an embezzler’s ex in order to see how much can be recovered is all it takes. The ex in question is Mona Stevens (Lizabeth Scott), a model in a dress store. The hook that snags Forbes comes in the form of a trip to the marina to see the boat Mona’s boyfriend bought her with the money he stole. Just a smile from the girl and then a quick ride in the speedboat are enough – Forbes is soon asking her out for drinks, and it doesn’t take much imagination to realize where all this is heading. The affair itself only goes so far though, and not necessarily due to any moral qualms on the part of Forbes at this stage. A bigger issue is the fact that the private eye employed by the insurance firm to track down Mona Stevens in the first place (Raymond Burr) is besotted with her to the point he not only roughs up Forbes, but is also prepared to destroy anyone who stands in the way of his desires.

André de Toth made a handful of films noir and I think this is the best of them, although a strong case can be made for Crime Wave too. He perfectly captures the sheer ordinariness and regularity of suburban life, its bright and brisk order imparting a feeling of living on a well maintained social conveyor belt. Everything operates like clockwork, including the people. Dick Powell perfectly captures the ennui of a man gradually becoming just another obedient automaton. Everything about him screams normality, his quiet tailoring, his discreet briefcase, and the inevitable slow slide towards middle-aged and middle-class mediocrity that accompanies all that. This is no disillusioned veteran either – he was no decorated war hero like the father of his son’s friend, he rode out the war in Denver, Colorado – just an everyday guy who has come to the appalling conclusion that this is all he’s ever going to be. When he wrinkles his nose at the comic books he reckons have given his son nightmares it’s hard not to see a bit of resentment in it for not being one of those colorful figures himself. It is to De Toth’s credit that there is never any overt call to pass judgement on this man, no nudge towards any moral superiority or cheap finger pointing. Film noir works best when characters are portrayed as people with flaws who sometimes makes poor choices that the audience get to witness. Navigating life can be an ambiguous business at best and the better noirs seek to capture that incertitude rather than encourage self-righteousness.

The portrayal of the two female characters in Pitfall is interesting, and the movie offers good roles for both Jane Wyatt and Lizabeth Scott. There are those who say film noir must have a femme fatale, that it’s one of the vital ingredients. I’m not sure that’s true, and I’m also not sure if Lizabeth Scott’s Mona Stevens should be characterized as such. Yes, she draws the men in the movie into danger, fatally in one case at least and the ending leaves it open as to whether or not that’s going to apply to another as well. Still, if she is a femme fatale, she is surely a reluctant one and arguably a victim of both her own weakness and the limited options open to a woman like her at that time. She acts as a magnet for negative forces, drawing danger to her without actively wanting to. Jane Wyatt as the wife is a tougher, more grounded and practical creation. All the way through she remains focused on the security of the family unit. It’s quite a clinical piece of work by Wyatt and the cool way she appraises the benefits and drawbacks of each new development that assaults her existence contrasts with the reckless opportunism of Powell and the emotional helplessness of Scott. Raymond Burr gets the creepy obsessiveness of his character across well, manipulating everybody and maneuvering them like chess pieces towards an endgame that will profit only him. The scene where he stalks Scott in the salon where she works is masterly in the way he humiliates her in plain view yet maintains a wholly innocent air. His bulk and physicality is employed effectively too, filling and almost overwhelming Powell’s office when he visits.

1948 was a particularly strong year for film noir in Hollywood, maybe one of the strongest, and Pitfall sits comfortably among the leading pack. Nobody puts a foot wrong in this movie and the script has no flab or slackness about it. It is a tight, direct story that asks plenty of questions but offers up no easy answers. In short, it’s a good movie and one worth watching.