Having already covered a number of westerns which have crossed over into noir territory, it’s time to turn the spotlight on one more. If we regard the mid-late 1940s as the heyday of film noir proper, then it’s only reasonable to find one of the strongest western variants within that time period. Blood on the Moon (1948) follows all the typical western conventions but uses a recognizably noir figure as its protagonist and employs the dark cinema’s trademark shadowy photography to emphasize both the sense of danger and moral ambiguity implicit in the story. As is always the case with these genre straddling examples, the film stops just short of being noir at its purest – the essential pessimism of that form rarely blending naturally or completely into a western story.

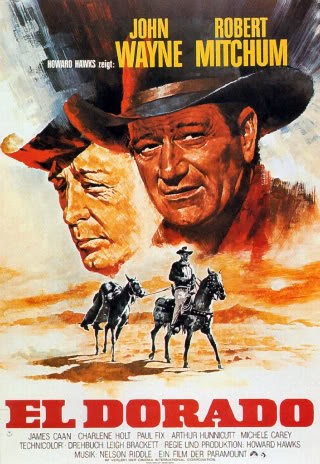

Jim Garry (Robert Mitchum) is one of those guys who’s no stranger to bad luck, a drifter with an ill-defined past first seen traversing a bleak and rocky ridge in the middle of a driving rain storm. When you see a guy strike a frugal camp and bed down to rest his weary bones, gaining some respite from the harsh elements, only to have his outfit smashed to pulp by a wildly stampeding herd of cattle, it’s easy to tell fortune isn’t exactly smiling on him. The herd belongs to Lufton (Tom Tully), and when Garry is taken back to the cattleman’s campsite he receives a kind of backhanded welcome. The west of Blood on the Moon isn’t an open or warm place, rather it’s a world of shadows, suspicion and wariness. Garry has ridden into a developing range war, the classic stand-off between the ranchers and the homesteaders. On one side we have Lufton, a rancher with a herd of beef that the Indian agent has refused to buy and which is about to be seized by the army unless it’s removed from the reservation post-haste. The opposition is a ragtag bunch of settlers, organized and dominated by Tate Riling (Robert Preston), and bolstered in strength by a handful of hired gunmen. Riling is denying Lufton access to old grazing land, ostensibly on the pretext that he’s defending the rights of the settlers. However, his real motivation is the opportunity to force Lufton into selling to him on the cheap, thus allowing him to make a financial killing through his dealings with the crooked Indian agent (Frank Faylen). Garry and Riling are old friends, the former having arrived due to the promise of a job with Riling. Initially, Garry isn’t particularly thrilled with the role he’s been cast in but a job’s a job. Although he doesn’t put it into words, it clear enough that Garry is uneasy about the double-dealing of Riling. What’s more, he’s clearly more impressed by the apparent straightforwardness of Lufton, and then there’s the attraction he feels towards the rancher’s younger daughter, Amy (Barbara Bel Geddes). For Garry, the turning point arrives in the aftermath of a violent raid on Lufton’s encampment that leads to the tragic death of the son of a widowed settler (Walter Brennan). With his realization of the depth of Riling’s ruthlessness, Garry experiences a crisis of conscience and finds his allegiance shifting.

Apart from the strong cast, Blood on the Moon featured a wealth of talent behind the cameras too. The story was adapted from Luke Short’s novel Gunman’s Chance, and has a scripting credit for the author himself. It appears that story caught the attention of the up and coming Robert Wise and he persuaded Dore Schary to let him run with the project. Wise had served a long and telling apprenticeship at RKO, editing Citizen Kane for Orson Welles and directing a couple of pictures for Val Lewton. In learning his trade, Wise had been keeping some esteemed company, and the experience showed up in this his first stab at directing a western. With cameraman Nicholas Musuraca achieving beautiful effects with light and shadow, Wise produced a western that’s dark, moody and heavy on atmosphere. There’s some good use of Arizona locations for the exteriors, but the most memorable aspect of the film is the gloomy and claustrophobic interior work. The low ceilings of the buildings, illuminated by guttering oil lamps, seem to press down on the characters, squeezing them and restricting their options as much as their movements. Although there are a number of noteworthy scenes, the highlight is arguably the brawl between Mitchum and Preston in a deserted cantina. This isn’t the typical cartoon scrap that we find in countless westerns; instead it’s a vicious and visceral affair that sees the two combatants slugging it out realistically. There’s no music to distract from the thudding, crunching landing of blows, and the naturalistic half-light makes the bruised and bloody faces and hands all the more convincing.

The first scene we shot after Mitch got outfitted was in the barroom. Walter Brennan was sitting at a table with a couple of pals and Brennan was very interested in the Old West, it was a hobby of his. And I’ll never forget when Bob came on the set, just standing there, with the costume and the whole attitude that he gave to it, and Brennan got a look at him and was terribly impressed. He pointed at Mitchum and said, “That is the goddamndest realest cowboy I’ve ever seen!” – Robert Mitchum – Baby, I Don’t Care by Lee Server, Faber & Faber 2001, p180

The above quote comes from Robert Wise and is as good an illustration as any of the degree of authenticity that Robert Mitchum brought to his western roles. Brennan’s observation was spot on for Mitchum does indeed look the real deal here and gives another of his deceptively easy performances. While he seemed to relish the physical stuff that I mentioned above the quieter scenes are played out with great subtlety and, throughout it all, he moved around the landscape and sets with tremendous grace. Robert Preston was good casting as Riling, turning on the false charm and grins when it suited and really bringing out the slippery side of the character. I thought Barbara Bel Geddes was impressive too, even though the western wasn’t a genre she did a lot of work in. Her role called for a fair bit of shooting and riding and she made for a game, independent heroine. The supporting cast is a long and starry one: Walter Brennan, Tom Tully, the wonderfully gritty Charles McGraw, Phyllis Thaxter, Frank Faylen and Clifton Young all doing good work and helping to flesh out the story.

Blood on the Moon is available on DVD from both Montparnasse in France and Odeon in the UK. Seeing as I have the two discs, I’m of the opinion that the transfers are identical – both sport the same significant print damage during the raid/stampede scene at around the half hour mark. In terms of extras, the French disc (with optional subs) has the usual disposable introduction, and the UK release has a gallery. Overall, I suppose the Odeon disc is marginally more attractive, at least in relation to its packaging which features a reproduction of the original poster art on the reverse of the sleeve. The aforementioned damage, along with various other nicks and scratches, show that no restoration work has been done and the transfer does tend to look a little soft. However, the feature is quite watchable and there are no better alternatives that I’m aware of anyway. The movie is an entertaining and striking one, a strong entry in the filmographies of both Mitchum and Wise. The development and resolution of the plot do dilute the noir credentials to an extent yet the strong visual style means it never strays too far either. Personally, I feel it hits the mark as a western and comes pretty close as a film noir too; as such, it’s recommended to fans of both types of movie.