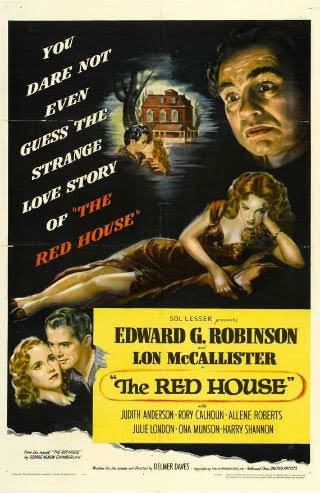

Seeing as I’ve reviewed the majority of the movies which directly featured the character of Wyatt Earp, I thought I might as well have a look at Powder River (1953). Even though this film does not have any character by the name of Earp in it, that’s where the inspiration comes from. Stuart N Lake’s book Wyatt Earp: Frontier Marshal is probably the most influential source helping to shape the legend which grew up around the famous lawman. Powder River is yet another adaptation of that book, and Lake is credited on screen as the author. However, for whatever reason, none of the real names of characters are used – perhaps Fox just didn’t want another Earp movie at that particular time. Anyway, the film represents another retelling of the Earp/Holliday story though it puts a slightly different spin on the central relationship, one that I’m not sure is altogether successful.

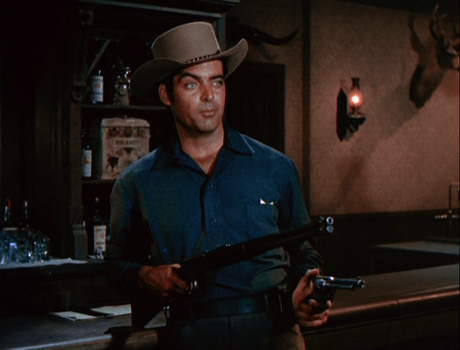

In this version of the story the Earp character becomes the colorfully named Chino Bull (Rory Calhoun). Chino – I’m sorry, but I’m not going to write a piece continually referring to a man as Bull – is a former lawman who has grown weary of the violence that goes along with that profession and has decided to try his hand at prospecting. A quick visit to town to pick up supplies leads to two events that combine to alter Chino’s chosen path. Firstly, some unplanned heroics connected to a can of peaches and a gun-happy drunk see him offered the job of town marshal. While he’s initially uninterested in putting on a badge again, a return to camp and the discovery of the fact his partner has been murdered and robbed brings Chino back to town, and back to his old life. As the newly appointed marshal, one of his first official acts is to crack down on crooked gambling and rigged tables. This means the temporary imprisonment of Frenchie Dumont (Corinne Calvet), the proprietor of one of the town’s saloons and gambling houses. This in turn sees the introduction of the Doc Holliday figure, here renamed Mitch Hardin (Cameron Mitchell). Hardin has a fearsome reputation as a drinker and a gunman, and also happens to be Frenchie’s man. Although Chino and Hardin butt heads to begin with, the former’s cool self-assurance wins over the gunman. As such, the central relationship, based on mutual admiration and respect, is established in a fairly familiar way. Now most Earp/Holliday films have concentrated on the friendship of the two men and how it is tested and then cemented by the feud with the Clantons. Powder River diverges from that formula somewhat by bringing in an insipid romantic triangle, the rivalry and distrust of a professional gambler (John Dehner), and a damaging secret which Hardin is harboring. I’d say that the extent to which the film works for the viewer is heavily dependent on how far one is able to buy into these aspects.

Anyone familiar with the Earp/Holliday movies will immediately recognize the characters of Chino and Hardin are only the thinnest of disguises. In addition there are sequences that directly mirror some of those in Dwan’s Frontier Marshal and Ford’s My Darling Clementine. Director Louis King had a long career, but he was no match for either Dwan or Ford. Having said that, King’s work on Powder River is by no means poor – it simply lacks the flair that Dwan or, more especially Ford, were able to achieve. Much of the action is confined to the town and interiors, but there are occasional scenes shot on outdoor locations. These exteriors are generally attractive, and one in particular, an attempted hi-jacking of a ferry carrying a stagecoach, is very well shot. The movie is largely a character driven piece, but King handled the action quite effectively whenever it does come along.

I like Rory Calhoun in westerns, and I think I’ve mentioned this before, he just seemed comfortable in the genre and frontier parts were a good fit for him. I feel the right word to describe his performance in Powder River is confident. Calhoun spends much of the running time unarmed, his character’s preference, and is never less than convincing as a man with enough self-belief and force of personality to keep the peace without resort to weapons. On the other hand, Cameron Mitchell is rarely seen without his custom rig. Again, this is entirely appropriate for a character living mainly on his nerves, and who has built a reputation for himself as a killer of men. Mitchell was a good enough actor, and gave some fine performances over the years, however, he didn’t have a huge amount of charisma. The Doc Holliday figure is one of the most interesting and, from an actor’s point of view, one of the more rewarding roles offered up by westerns. Almost all the performers who have played this part at various times have created something memorable. Of all those I’ve seen, Mitchell’s take on the role was among the least satisfactory, for me anyway. I can’t say he did poorly; he certainly got across the self-loathing aspects of someone who has witnessed his life take a route he had never intended. To some extent, the problem stems from the character arc Hardin goes through, but that’s not it all either. Ultimately, Mitchell’s performance never quite measures up to the other screen depictions of Doc Holliday – it may be a little unfair to compare performances in this way, but it’s hard not to. John Dehner was a man who always brought a touch of class to his parts and his name among the credits is something that I look forward to. He has a medium size role in Powder River, and I think the film would have benefited had he been given a bit more to do. There are two female parts in this production, those of Corinne Calvet and Penny Edwards. Of the two, Calvet did by far the most interesting work, coming across as tough, sexy and sassy from her very first appearance. In contrast, Penny Edwards just feels very colorless, and her romantic involvement with Calhoun and Mitchell never catches fire or is the least bit convincing.

Rory Calhoun hasn’t been all that well served on DVD, with the dearth of titles being especially noticeable in the US. Generally, he’s fared a bit better in Europe, and Powder River has been released on disc in Spain by Fox/Impulso. For the most part, the transfer is quite good. This is an extremely colorful movie and the Spanish release reproduces that aspect pretty well. It can appear a little dark at times, notably during interior scenes, and there is some mild flickering on occasion although none of that is particularly distracting. The disc allows the Spanish subtitles to be disabled via the setup menu, and extras are the usual gallery and a few cast and crew text pages. Powder River is a modest western, never straining to overreach itself and delivering reasonably satisfying entertainment. Personally, I’m always up for another version of the Earp/Holliday saga, and I do appreciate the fact that the filmmakers tried to bring something slightly different to the table with this movie. However, while the attempts to alter the dynamic of the relationship between the two leads is interesting, I don’t honestly think it works that well in practice. There are a handful of good performances and the film is worth checking out, but it never seriously challenges the better Earp movies.