You want to go in like this? You want people to talk about it the the rest of their lives, how the mouse brought back the cat?

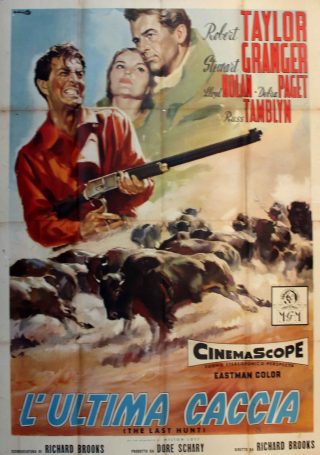

The taglines used by the marketing men for The Wild North (1952) tended to emphasize the man vs nature and and the man against man aspects of the movie. These elements are there without question, but I find much of the story boils down to the matter of reversals as well as our old acquaintance redemption. It is one of those bracing and beautiful outdoor adventures – some might term it a western, but I’m not convinced and I see no need to hang that label on it – that places its characters, both willingly and unwillingly, beyond the bounds of civilization and invites us along to observe how they react and respond to the challenges this presents them with.

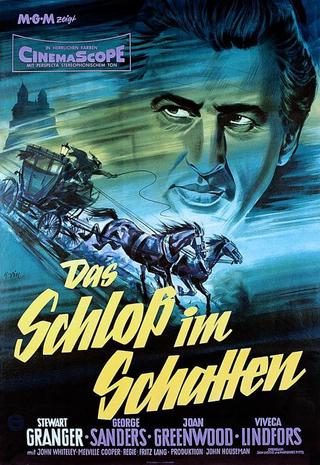

More than one wilderness based movie has opened with the visit of the protagonist to town or to some kind of settlement, and such stopovers almost inevitably lead to trouble. Such is the case here as Jules Vincent (Stewart Granger) makes one of his infrequent trips back to what passes for civilization, looking for a chance to get drunk and maybe find some attractive company. Well the liquor is easy enough to come by and the nameless Indian girl (Cyd Charisse) singing in the saloon satisfies on the other score. However, he also manages to draw the attention of a loud, aggressive type called Brody (Howard Petrie). Despite their initial antipathy, Vincent agrees to take Brody along as a passenger on his journey back north alongside the girl who has convinced him of her desire to return to the wild country she hails from. It’s giving nothing in particular away here when I say that Brody soon winds up dead. His demise is never shown – this is not to create any sense of ambiguity regarding his fate, but I guess it’s meant to lessen the impact of the viewer’s knowledge that Vincent has become a killer. The reason given is that Brody’s determination to take on the lethal rapids was putting everyone’s lives at risk yet Vincent has no faith in a jury of townsmen’s ability to appreciate the necessity for his actions. So he takes the girl and runs north, bent on losing himself in the environment he knows best. As with all the best Mountie stories however, the law, in the shape of Constable Pedley (Wendell Corey), is not to be denied its man.

What follows develops largely into a two-hander as Pedley arrests Vincent and sets out on the long and treacherous trek back though the harsh winter conditions. One would expect conflict and friction between the two men, which is indeed present, but this doesn’t take refuge in the hackneyed hiding places of some lesser films. The rivalry is tempered from the outset by a grudging mutual respect and fondness, the kind that only two very different characters can experience. Pedley has a job to do and will see it through no matter what yet he has no personal axe to grind with his captive and actually likes him. Similarly, Vincent sees in his captor a man he can admire to some extent. In spite of the apparent contrast in one man’s untamed ebullience and another’s steely but witty intelligence, there is a strong sense of humanity binding these two together. That bond becomes ever stronger and more vital as they both face threats to life and limb from thieves, an avalanche, and a terrifyingly tenacious pack of wolves.

Stewart Granger is in fine form in his second of three films with director Andrew Marton, King Solomon’s Mines and Green Fire being the others. He gets across the brashness of the trapper, the love of the outdoors (something I think the star shared in reality) and also that streak of ruthlessness that must surely be found in all such men. There are a couple of occasions where that latter aspect is allowed to manifest itself even if it’s quickly suppressed as his character’s basic humanity asserts itself more forcefully. However, it is there and it lends an authentic air of danger to Jules Vincent. Set against that is Wendell Corey’s much quieter work, and the two approaches genuinely complement one another. Corey could appear stiff and far too reserved in certain films yet he brings a marvelously controlled charm to this role. He’s no rigid authoritarian, but nor is he a pushover. While he’s competent and organized, he has heart and humor as well as a well judged awareness of his own limitations and loneliness. Ultimately, I think this is what makes the film work, the acknowledgment by both men of their respective strengths and weaknesses. As the threats pile up and the roles are reversed, it’s the redemptive reflex they both respond to that give it its heart. In their own different ways they save each other and by doing so save themselves. Cyd Charisse is only in the picture intermittently and anyone waiting for some tiresomely contrived romantic triangle to arise will be disappointed. She is absent from the long main section and I think that’s actually just as well as it allows the focus to remain firmly on the struggles of Corey and Granger in the snowy wastes. Support comes from an abrasive Howard Petrie, Ray Teal as a shifty trapper, Houseley Stevenson (in one of his last feature roles), and J M Kerrigan.

Films which use the great outdoors and wilderness landscapes as their backdrop can sometimes drift into mindless action that loses its impact when overused or they can linger too lovingly on the visual splendor of their locations. The Wild North avoids these pitfalls by remembering that the essentials of the story stem from the character dynamic, that its success derives from within rather than from the more superficial elements. It’s a matter of balance, something which I feel this movie achieves and it manages to become a positive, uplifting, life-affirming experience in the process.