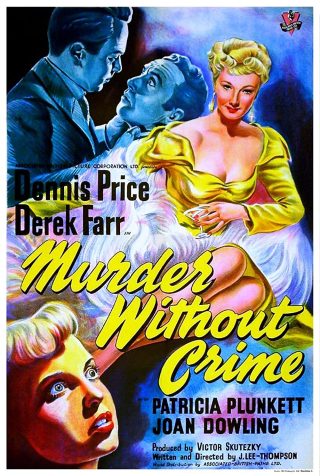

Looking at the beginning of a filmmaker’s career can be an eye-opener, either for good or bad reasons. Some directors start out with only a shadow of the confidence and assurance they would later develop, resulting in debut efforts that are clearly the work of a novice. Others hit the ground running, creating the illusion that they had been in this line of work forever. Murder Without Crime (1950) was the first feature directed by J Lee Thompson, a man whose subsequent career would be a lengthy and varied one. The movie has a great deal going for it in terms of both pacing and visuals, although there are other aspects of it which are more problematic. All told though it suggested that the man in the director’s chair had a promising future ahead of him.

Murder Without Crime is a self-contained affair following the fortunes of just four Londoners over the course of one evening. Stephen (Derek Farr) is, according to the narrator, an author of moderate success. He is married to Jan (Patricia Plunkett), but it does not appear to be a happy union. Jan suspects infidelity and Stephen doesn’t have the demeanor of an entirely trustworthy man. They row, tempers become frayed, accusations and threats get tossed around, and Jan storms out vowing never to return. What then is a churlish and vaguely immature man supposed to do under the circumstances? Why, allow his smug and supercilious landlord Matthew (Dennis Price) to take him out on the town to drown his sorrows in a Soho night club. That then is the location where the fourth piece of the ensuing puzzle makes her appearance; Grena (Joan Dowling) is a hostess in the club and the lovelorn Stephen catches her attention. To cut to the chase, Stephen and Grena eventually end up back at his place, where he veers disconcertingly between maudlin and passionate while she is simply kittenish. Things take a nasty turn though with Grena feeling rejected and insulted before it escalates into a tussle over an antique dagger that sees Stephen shove her, causing her to fall and strike her head.

Such a turn of events would be enough to panic even the most levelheaded and self-assured individual, neither of which characteristic could be used to describe Stephen. His first thought is to conceal the deed, but he is not taking account of the suspicious and predatory nature of the ever vigilant Matthew in the flat below. The opportunity now exists to apply some pressure on the hapless Stephen, with Matthew sadistically teasing and tormenting him with allusions to his guilt, toying with him pitilessly before blackmailing him.

J Lee Thompson had started out as a writer and one of his earliest plays went by the name of Double Error. It seems to have enjoyed some success, being performed in the West End as well as later revivals in the US. In 1950 Thompson had the chance to make his first movie and Double Error was adapted for the screen as Murder Without Crime. The stage origins are apparent in the small cast and limited locations but the cinema version has some very striking visual flourishes, with sharply canted angles and moody noir style cinematography helping to build up atmosphere and suggest a world where the mentality of the people we follow is as skewed and quirky as the imagery on the screen.

Everything moves along at a comfortable pace, scenes never drag and it all wraps up in a way that is brisk without being rushed. However, there are some weaknesses that shouldn’t be glossed over. Firstly, there is a voice-over that adds little to the proceedings and comes off as smug and smarmy where I suspect it was actually aiming for knowing sophistication. Then the score by Philip Green is one of those intrusive efforts, making its presence felt far too strongly and drawing attention to itself far too often – I have always felt a score ought to complement the visuals, enhance the mood rather than stomp all over it. Finally, there are the characters who people this drama. I don’t reckon it is necessary for audiences to be able to identify with the characters they watch but there should be someone they can at least sympathize with. The problem with Murder Without Crime is that nobody is actually all that likeable.

Dennis Price was a fixture of many British movies throughout the 1940s and 1950s, excelling at playing men at once remote and bilious. Kind Hearts and Coronets may well be his best work but there are numerous examples of delicious unpleasantness in his list of credits. As Matthew he is seedy, louche and superior, and downright mean-spirited. Up against Price is Derek Farr, in a role that really needs to have some feature we the viewers can root for. What we get, however, is a portrait of a weak and truculent type, a man who is struggling to save up to make a down payment on a chin. While Stephen surely feels sorry for himself and worries a lot about how everything will pan out, I was of the opinion that any misfortune he suffered was richly deserved.

The women fare only marginally better. Patricia Plunkett rightly walks out on Stephen at the beginning, but her resolve weakens far too quickly. When she returns it is hard to see how she is justified in helping out this man who is clearly unworthy of her. That she continues to do so even after she learns how he behaved had me scratching my head. The tragic Joan Dowling does some good work as the clinging hostess but, once again, it is difficult to like her. The fact is all four of these actors turn in good performances, but the the characters they play are for the most part distasteful.

Murder Without Crime is a modest picture, telling a simple yet twisty story economically. Network released the movie on DVD almost a decade ago and it looks like it has now gone out of print, although used copies can still be picked up at reasonable prices. That old DVD was quite strong and boasted the kind of transfer that did justice to the visuals. It is a tight little crime story from a director who was just starting out and even if it has some weaknesses (which I hope I haven’t overstated here), it still makes for an enjoyable way to spend eighty minutes of your time.