“I suppose that when you spend most of your life in one profession you develop what could be called an occupational point of view.”

Write what you know. Isn’t that the classic line of advice offered to all budding scribes? When Humphrey Bogart’s character speaks those words above as the camera pans on the opening scene of The Barefoot Contessa (1954) there is at the very least a flavor of that sentiment on display. And if Hollywood knows anything, it surely knows about the path to fame and about each and every pothole mining the route that leads there. Self-awareness, so long as it’s kept on a short enough rein to prevent its spinning off into self-indulgence, can be healthy; it grants perspective and that along with what I can only term soul are the essential ingredients of creativity. So “Hollywood on Hollywood” has been a productive sub-genre over the years, permitting the movies and their makers to take a look at themselves and inviting the viewer to peel back a corner of the mask for a glimpse of what lies behind. Such films generally fall into two categories, ranging from the celebratory to the acerbic. The Barefoot Contessa lands somewhere in the middle, perhaps because it is itself a story pitched halfway between Hollywood exposé and a meditation on fate.

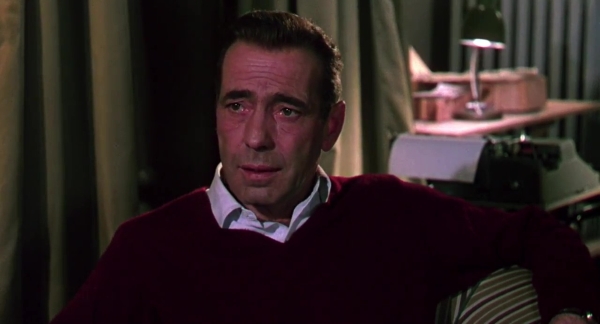

That air of fatalism pervades the movie, right from the rainswept introduction in an Italian cemetery, where a pensive Harry Dawes (Humphrey Bogart) casts his mind back over the few short years when he came to know the titular character. He stands a little apart, slightly detached from the other assorted mourners, although all of them are separated from each other in pairs and little clusters. This detachment is somehow appropriate, as fitting in its own way as the low key setting of this last farewell. These people have gathered to pay their respects to Maria Vargas (Ava Gardner), a one-time flamenco dancer from the back streets of Madrid who would later find fame on the screen as Maria D’Amato, before ending her life as the Contessa Torlato-Favrini. It’s appropriate because although the movie traces the brief rise and fall of Maria Vargas everything that is shown is filtered through the perceptions of others, those who tell her story to the viewer. Harry Dawes does the lion’s share of the telling, he was the one who was credited as having “discovered” her or mentored her in any case. As we segue into a flashback to the club in Madrid where Maria dances by night, the tone is set with great deftness. Her dancing is never observed, only the reactions of the audience provides a sense of her. While the camera roves around the assorted patrons, it becomes clear the woman who holds them all rapt is offering a reflection of what they all feel – the responses vary from frank admiration to surreptitious desire, as love, passion, frustration and shame flash across the screen and the faces of the assembled watchers in waves. And then it’s over, the dance is done and the star vanishes back to her own privacy as the beaded curtain swings back into position.

In what might be taken as a subtle dig at Hollywood forever playing catch-up with regard to popular trends, no sooner has the main attraction vacated the stage than the people from the movies arrive. The aforementioned Harry Dawes is tagging along with Kirk Edwards (Warren Stevens) a buttoned up producer reminiscent of Howard Hughes, Oscar Muldoon (Edmond O’Brien) whose glittering eyes and glistening face speak of perspiration and PR, and a burnished blonde courtesan by the name of Myrna (Mari Aldon). Kirk Edwards is a mean vulgarian, a shell of a man high on his own sanctimony and motivated only by the manipulative power of the dollar. He has flown his entourage all the way to Spain to see Maria Vargas dance and maybe offer her a contract. And now he has arrived too late, but such a man cannot countenance this kind of ill-fortune. He orders, savoring the humiliation the whole process entails, first Oscar and then Harry to fetch the aloof dancer to his table. While Oscar sweats and schmoozes Maria out of agreeing to a screen test, Harry is left with literally no option but to track down and persuade her to change her mind. Where Oscar’s sweat failed, Harry’s sincerity triumphs and Maria is on her way to stardom.

Exit Harry, temporarily. And enter Oscar, the vacuous nature of the publicity man firmly to the fore as he takes up the narration, charting the course of a life and spirit he freely admits he could never quite fathom. Of course Oscar doesn’t do depth, he does his master’s bidding. Partially due to the liberating effect of being around a woman who has no time for the fakery and front that stardom seems to demand, he sees his world view shifting ever so slightly. His remit is to guide us through the downfall of Kirk Edwards and Maria’s move on to the next phase of her life as the principal exhibit of Alberto Bravano (Marius Goring), a Latin playboy with no discernible character. This is a shorter interlude, a stepping stone on the way to Maria’s ultimate destination. Soon, the tale is taken up by Vincenzo Torlato-Favrini (Rossano Brazzi), the tortured aristocrat who is tragically incapable of real love, able only to venerate and deify. It is he who commissions the marble statue of Maria that will ultimately mark her final resting place, a cold approximation of beauty that is as cold and blank as his own helpless passivity.

Ava Gardner’s Maria Vargas drifts through the movie, and I use that term quite deliberately. As I said, at the beginning, the story is deeply fatalistic. Both by her words and her actions the lead character is presented as a woman unable to, or perhaps unwilling to, completely break from the past and take command of her destiny. The whole barefoot business ties into this, an explicit acknowledgment that the past is an integral part of oneself, functioning either as a brake on ambitions and aspirations or as a means of grounding one in reality. I don’t say this is a philosophy I particularly sympathize with, but it is there, it defines the whole mood of the piece and is well realized. Ava Gardner’s performance here is key to that realization and is almost a subversion of her typical screen persona. Earthy is the word that frequently springs to mind when I think of her rather than ethereal yet it is the latter quality which she conveys throughout much of the film. Sure she has her moments of fire, but she never allows her natural vigor to overshadow that acceptance of a life directed by the golden threads of the Moirai.

The Barefoot Contessa is not a film that works for everybody, maybe due to that air of languor that grows out of its core fatalism. Then again it might be the wordiness of the script that bothers some, but I’d argue that anyone knowingly approaching a Joseph L Mankiewicz film and finding that aspect an issue ought to know better in the first place. Personally, I’m inclined to think that the third act, that beautifully shot and achingly poignant Italian interlude is most problematic. It is not a question of where the film is going or even where it ends up that hurts it, rather it is the playing of Rossano Brazzi that I think takes the edge off it all. Although I’ll concede he gets the futile desperation of his character across, I don’t think Brazzi was ever the most magnetic presence at the best of times and that becomes an issue here. It is undoubtedly a tricky part to carry off, but I just do not see him as the object of Gardner’s grand passion, the man who has that something which she never found elsewhere. Without that, one of the main props of the story is seriously weakened.

Bogart’s name was top of the bill and his bookending of the narrative is nicely judged. His later films weren’t always all they could have been, even if his own work was as strong as ever for the most part. His peak years were often characterized by that tough insolence that has spawned so many imitators, but he had more to him than that when he wanted or was allowed to show it. The Barefoot Contessa lets him reveal a warmer side than usual. Even if it’s tempered by the weariness and regret that came easily to him, there is an empathy on display which is very attractive. In support Edmond O’Brien sweet talked his way to an Oscar playing Oscar; there’s a degree of showiness as there nearly always is with award winning turns and he makes what is on paper a pretty miserable character more appealing than he probably ought to be, still it’s an engaging and memorable bit of work. Warren Stevens achieves an almost reptilian stillness as the soulless tycoon and it’s fun seeing him face off against a very theatrical Marius Goring in their big confrontation scene. Valentina Cortese, Elizabeth Sellars and Mari Aldon all have their moments even though their parts are relatively minor.

The Barefoot Contessa got a Blu-ray release in the US from the now defunct Twilight Time and then later in the UK via Eureka. I have that UK BD which now appears to have gone out of print and it’s a fine looking transfer of the movie that makes the most of Jack Cardiff’s beautiful cinematography. I don’t always mention scores or soundtracks, which I know is remiss of me, and so I want also to take the opportunity to draw attention to Mario Nascimbene’s evocative work on the movie. I wouldn’t want to claim The Barefoot Contessa is a flawless work as I am aware that it has its weaknesses and doesn’t appeal to all. However, it is and has long been a favorite of mine, ever since I stumbled on an early evening TV broadcast nearly forty years ago.

Well, that about wraps it up for 2023. I’d like to say thank you to everybody who came along for the ride over the last twelve months. Here’s to 2024 and here’s hoping it brings peace and happiness to us all. Happy New Year!