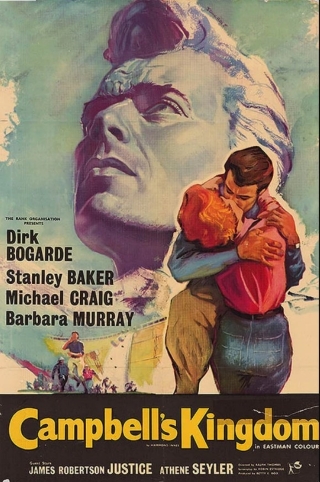

When is it reasonable to call a movie a western? Well the simple answer would be when it’s located within that area typically defined as the American West, essentially the far side of the Mississippi, and inside a relatively short period of time, although the jury is surely out on how rigorously the latter should be applied. Actually, even the geographical aspect is given a bit of leeway too in reality. Plenty of westerns have been set in Mexico and others have stretched up into Canada too. The action in Campbell’s Kingdom (1957) takes place north of the border in contemporary Alberta so some might like to think of it as a western. Personally, I wouldn’t call it such, I see no need to hang that label on it or to scratch around in an effort to shoehorn it into the genre. It’s a British outdoor adventure, with a seam of intrigue running though it and a hint of romance almost as an afterthought. It’s also a very enjoyable movie with splendid visuals and some well executed sequences that blend action and suspense successfully.

The whole story revolves around Bruce Campbell (Dirk Bogarde), newly arrived from England in the frontier town of Come Lucky. That’s one of those place names that positively drips irony, the kind of small settlement just about hanging onto the ragged coattails of civilization, its economic viability precarious at best. And there’s irony too in the fact Campbell should end up there. If the town has a dubious future, then the lead character is a man with none at all. He’s been given only months to live and has made his way half way round to world to take up the tainted legacy left him by his grandfather. The old man, whose body is only glimpsed in the opening scene, has died an outcast, widely blamed for a swindle that fleeced the town’s inhabitants. I guess no man likes the thought of departing without leaving something positive behind and that was true both of the elder Campbell and the doomed nephew now seeking to make restitution for the past and peace with the present. Campbell’s route to familial redemption is not be a smooth one, the land bequeathed to him by his grandfather was thought to hide reserves of oil but the survey results filed appear to contradict that. Instead of providing a source of wealth that might help the town thrive once more, Campbell’s “kingdom” is due to be flooded subsequent to the construction of a dam. Morgan (Stanley Baker) is the ruthless and pugnacious construction boss who is determined to get the dam up as soon as possible, and Campbell and his kingdom swept aside. The plot basically devolves into a race to prove the existence of an oil field, and thus restore his family’s reputation, before the construction outfit and the mining interests behind it sink the entire endeavor.

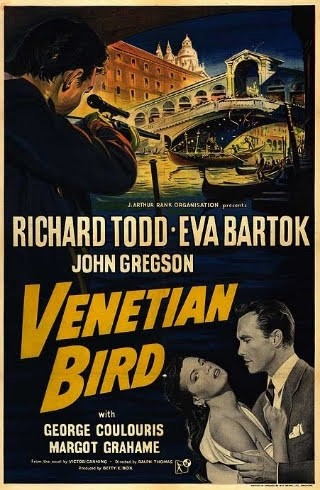

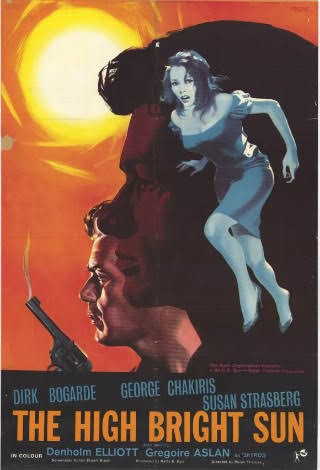

Campbell’s Kingdom is an adaptation of a Hammond Innes novel, the script of which was initially worked on by Eric Ambler,but the final product came via another novelist turned screenwriter Robin Estridge, with the cooperation of Innes himself. Typically, an Innes novel focuses on a lone protagonist, usually some competent, professional type, thrust into an adventure that has a reasonably compelling mystery at its core and that makes use of a potentially threatening natural environment. All of these elements are present in Campbell’s Kingdom, with the doomed hero aspect and the sins/secrets of the past angle exploited quite effectively. The location shooting, Ralph Thomas directing and Ernest Steward handling the cinematography, with the Italian Dolomites standing in for Alberta, has a crisp beauty and integrates seamlessly with the interiors filmed at Pinewood Studios. Thomas might appear a bit of a left-field choice for this type of story, he made a lot of quite light comedies (not least the series of Doctor adaptations of Richard Gordon stories with Dirk Bogarde), but the fact is he was one of those versatile journeymen able to take on almost anything that came his way. He made a few good thrillers in Venetian Bird, Checkpoint,The High Bright Sun and The Clouded Yellow, a slightly pedestrian but not wholly unworthy remake of The 39 Steps, as well as the classic war movie Above Us the Waves and some interesting dramas in The Wind Cannot Read and No Love for Johnnie. The section where a landslide is triggered and a bridge dynamited to buy enough time for a convoy of trucks to sneak its way up the mountain via a cable hoist is deftly put together and offers some genuine suspense.

I don’t suppose Dirk Bogarde is anyone’s idea of an action hero, but he’s not playing that anyway. His character is a former insurance clerk, and one who has been in poor health to boot. As such, he does fine as the part is written and a few criticisms I have come across, both current and contemporary, questioning his suitability for the role seem churlish as a consequence. He was always better in more introspective moments and there are a smattering of those which allow him to play to his strengths. Stanley Baker has a one-dimensional part as Morgan, lots of drive and bullishness so he can show off that provocative intensity he displayed so well. It never taxes him though and there’s not much shading, but that’s no criticism of the man’s performance. Michael Craig is stoic and reliable as the sidekick – he has the somewhat thankless task of playing a man who loses out in the vaguely insipid love triangle, and doesn’t even get the chance to play a scene venting his frustration. Barbara Murray represents the other side of said triangle and she does have her moments, she’s not relegated to the type of decoration and background hand-wringing which sometimes befalls heroines in action films. The rest of the cast is a virtual Who’s Who of British cinema: Athene Seyler, Sid James, John Laurie, Robert Brown, Finlay Currie and so on. This results in a variety of ersatz accents that sometimes hit the mark. James Robertson Justice has a biggish part as the drilling expert and all the way through he speaks with the oddest Scottish burr I have ever come across – perhaps he was supposed to have some Scandinavian connection?

Campbell’s Kingdom was released on a fabulous looking Blu-ray by Network in the UK before that company folded. It also came out on DVD before that, and I think it’s had a BD release in the US as well. This is one of those movies that has no pretensions whatsoever. It’s not of the thick-eared variety, but nor is it straining to be anything other than a solid adventure. All told, this is an undemanding piece of entertainment with its heart in the right place.

This is a couple of days early – what’s a day or two between friends anyway! – but it’s close enough to the anniversary of my first ever blog post, which was all of seventeen years ago. There have been a fair few movies watched, written up and talked about in that time.