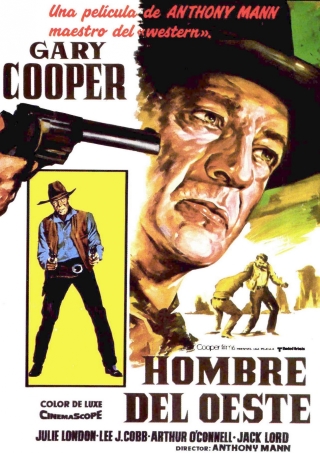

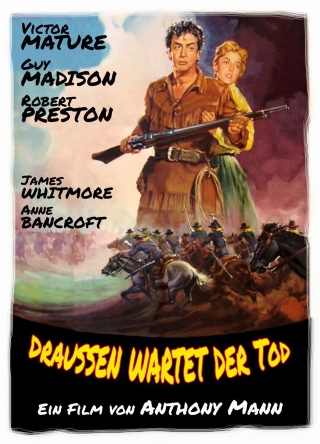

The western, when it hits the heights of its artistic potential, traces the route of its characters along a path that leads them to salvation, redemption, fulfillment or any combination thereof. When this is achieved then the audience gets to follow, to catch a glimpse of, and thus on some level share vicariously in those rewards – this is one of the riches of cinema and it’s to be found in abundance in the very best of the classic era of the western, not least as it approached the zenith of its power. And for directors who could be said to have had a clear view of what they wanted to do within the genre this same progression towards a destination marked fulfillment can also be discerned. Anthony Mann started making westerns at the beginning of the 1950s with Devil’s Doorway and Winchester ’73 and, particularly in that great cycle with James Stewart, dug deep into the heart of the genre. His work laid bare the tormented souls of his characters yet also applied a kind of spiritual healing balm that meant the harsh journeys he took them on finished up at a place that promised them peace. Man of the West (1958) follows this template and while it wasn’t the last of Mann’s westerns, it does represent the apogee of his work in the genre.

On the surface, the plot of Man of the West is a simple and straightforward one. Link Jones (Gary Cooper) is a man clearly out of his element, a true man of the west who is spooked by his first view of a train and bemused by civilization’s apparent determination to squeeze him into the smallest space manageable. Still, the west of his past is never far away and a neatly executed raid sees him relieved not only of his luggage (and the money he’s been carrying to hire a teacher for his town’s new school) but also the discomfort of his poorly designed seating. Stranded in the middle of nowhere in the company of garrulous card sharp Sam Beasley (Arthur O’Connell) and saloon singer Billie Ellis (Julie London), he has no option but to set out in search of shelter. The thing is though, Link is no helpless hick – he evidently knows where he’s headed as he soon comes upon an old homestead that he seems familiar with. In short, this is very definitely a man with a still unrevealed history, one who thought he had outrun that past only to find it catching up with him and drawing him back into its unwelcome embrace. There had been hints of that in his shifty avoidance of the law back at the train halt, but it’s here that the full extent of his involvement with criminality is dragged out into the light, or into the flickering shadows of a dank and dangerous cabin to be precise. The gang who robbed the train are taking orders from Dock Tobin (Lee J Cobb), the notorious uncle who brought up and shaped – or perhaps twisted – the character of the younger Link. His delight at having his protégé back is matched by Link’s carefully concealed disgust at being snared once again by the kind of people he thought he had escaped for good.

The tone of the movie shifts radically at this point. Link’s caginess grows and is clarified at the same time, and the worthlessness and utter inhumanity of Dock and his gang increases by the minute. The cabin itself is hugely oppressive, shot by Mann in the shadowy menace of guttering flames with a heavy and smoke darkened ceiling regularly in view, its narrow and tight dimensions seem to press from every side. As Dock raves and booms about a past steeped in blood and brutality, Link’s burgeoning despair is just about held in check. He had set out to recover the money entrusted to him by poor and trusting people and now finds himself responsible for both his own well-being (he has a dependent wife and children relying on his safe return) and that of two helpless people he has led into danger.

This long sequence in the cabin gradually takes on the feel of a visit to one of the deeper circles of Dante’s Inferno, where depravity is let loose and one starts to wonder if light will ever be permitted in again. Dock resides here, a malignancy at the center of a web he has spun around himself, goading his companions to ever greater excess. When the degenerate Coaley (Jack Lord) demands that Billie strip for their amusement and holds the outraged Link captive, a knife cutting into the flesh of his throat, there is a real sense of terror on show. This entire section is impossibly tense, dark and forbidding, so much so that there is a palpable sense of relief when events move the characters out, when a new dawn breaks and the possibility of getting into the open beckons.

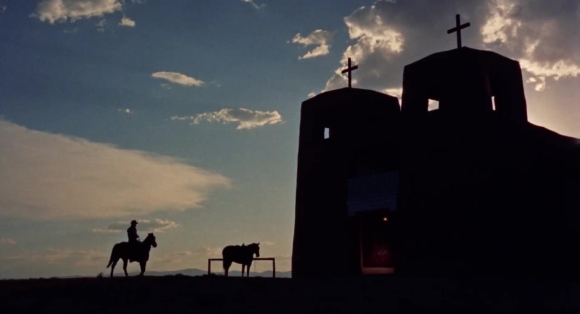

Here, in the closing act of Mann’s beautifully shot tragedy, those classic themes of revenge, redemption and renewal are played out against a dusty and sun-bleached backdrop that is as unforgiving as it is honest. Link is handed the opportunity to avenge the indignity and barbarity of Coaley, meting out a retribution that is chilling in its bleakness and also unsatisfying as a result of the further hurt it unwittingly inflicts on the innocent. The message of course is that revenge never achieves anything of value, a theme that Mann revisited time and again throughout his career. By the time it all draws to a conclusion with a sudden gunfight high up on one of the director’s characteristic elevated spots, more horror has been confronted and further pain endured. For all that harshness and violence and loss, Mann’s essential commitment to the durability and resilience of humanity, to the ultimate triumph of decency over malice never falters. When the damaged survivors come together briefly at the end before the inevitable parting, making their peace with themselves and the challenges posed by life itself, there is no doubt that catharsis and renewal have been earned and won. This holds true of the characters, maybe it can be said of the director, and it brushes off on the viewer too .

I know the casting of the movie has not met with universal approval, but I find it works fine for me. Sure Cooper was probably too old for the part as written but his work here allows me to ignore that. The fact he had such a natural affinity for western roles is a terrific boon in itself and then there is that minimalist approach to acting he had perfected over the years. Those eyes that dart like fugitives while the face remains taut, that guarded catch in the voice, the pauses and the silences all add up to wonderful screen acting and I find it hard to see how anyone else, regardless of their age, could more convincingly impart the mix of caution, fear and guts required. Does Lee J Cobb crank it up too high? Maybe so, but as I see it his character is a monstrous creation, deluded and demented by his own turpitude. Dock Tobin lives in an unreal cocoon and surrounds himself with lowlife sycophants so it’s arguably a valid interpretation on the part of the actor to play him with such studied bombast.

Julie London’s lonely saloon girl is well realized and she deftly captures the precarious position occupied by a woman in such circumstances. All her western roles were fine but this one presents her with a number of challenges – the natural toughness of the saloon singer is neatly juxtaposed with her innate vulnerability and she handles the scenes where she’s subjected to both physical and psychological assault with sensitivity and grace. She excels in her scenes in the cabin and barn, playing effectively off Cooper’s reticence and reserve, and then has two other memorable scenes with her leading man in the wagon, the first tender and bittersweet while the second exposes the full horror of Tobin’s bestial character. In support John Dehner plays it tightly coiled as Cooper’s cousin, coolly disgusted by the decline he sees in Tobin and never once deceived by Link’s maneuvering. Royal Dano is memorably manic as the mute Trout, Robert J Wilke sneers and threatens on cue while Arthur O’Connell is all blather and blarney till he stops a bullet at the end of one of the film’s most shocking scenes.

Man of the West saw Anthony Mann take the western to the place he wanted it to be. All the themes he’d touched on and explored throughout the preceding decade are on view and placed under the microscope. Having won acclaim as a director of film noir, his westerns hold onto some of that darkness – the visual aesthetic may have gradually become less pronounced as he moved to frontier tales but the fascination with the less savory aspects of humanity remained. What separates his westerns from his earlier noir work though is the focus on reaching for something finer, the scramble towards redemption and an escape from the darkness both within and around the characters. By the time he made Man of the West he had discovered how to set those characters firmly on that path.