Budd Boetticher is celebrated, and rightly so, for the seven westerns he made with Randolph Scott in the late 50s. Seminole was produced just a few years before those collaborations and, while it’s a satisfying enough picture, it’s not quite up there with his best. One could, I suppose, quibble about its credentials as a western due to the setting (Florida) and the time period (1835) but I feel it’s as near as makes no difference.

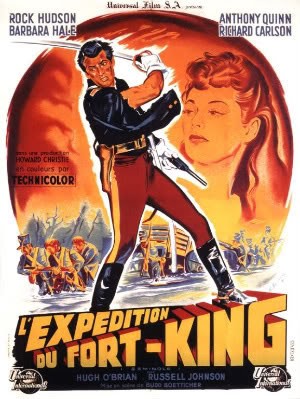

The story, most of which is recounted in a long flashback sequence, follows the newly appointed Lt. Caldwell (Rock Hudson) who is travelling back to his birthplace in Florida to take up a position at Fort King. His arrival coincides with the beginnings of an uprising among the Seminole, provoked by a government plan to uproot the tribe and move them west to prevent their presence slowing down the nation’s expansion. Within this framing story there’s further conflict due to the revelation that Caldwell’s boyhood friend, the half breed Osceola (Anthony Quinn), is not only the chief of the Seminole but is also vying for the affections of his sweetheart Revere Muldoon (Barbara Hale). While Revere shuttles back and forth in the role of intermediary between the Seminole and the army, a plan is set in motion by the fort’s commander, Major Degan (Richard Carlson), to strike at the enemy in their Everglades homeland and thus preempt any further threat.

The film raises a number of issues, only a few of which are fully explored. The main conflict is the internal struggle which Caldwell experiences between his loyalty to the army and his inherent sympathy for the Seminole he has known all his life. This leads to his being suspected of treachery by his superiors and his eventual court martial. The film tries hard to show the Seminloe in a positive light (mostly due to the performance of Anthony Quinn) but generally takes the middle way, since the army is portrayed as being reasonably even-handed with the exception of the uptight martinet Major Degan. This leads to a bit of a pat, upbeat ending. Much stronger is the middle section where Degan leads his troop on a disastrous march through the steamy swamps with a huge cannon in tow, all the while insisting they keep their tunics buttoned to the collar as per the regulations. One of the more interesting themes, and the film really only touches on it, is that of miscegenation. It is quite clear that Revere has been involved in a long-term relationship with Osceola but, after a brief mention by the chief of how white society would frown on this, she quite happily drops him and contents herself with a future by Caldwell’s side.

Rock Hudson is just about adequate in his role as the new officer forced to make war on his one time friend but his acting is a little too wooden to do justice to a part which requires him to experience a good deal of inner turmoil. Anthony Quinn fares better as the reluctant war chief whose living in both the white and Seminole cultures has afforded him an understanding of both. However, the role, as written, calls for a little too much nobility on his part and so weakens the chracter. Richard Carlson’s Degan is a very one dimensional portrayal which consists of much manic ranting and petty spitefulness, still he makes for a good hissable villain. As for Barbara Hale, she hasn’t a lot to do except act as a plot device and provide some decoration. Lee Marvin shows up in one of his small early parts as Sergeant Magruder and adds a touch of class to the proceedings, as he always did. Boetticher directs the whole thing at his trademark brisk pace, and does his best work when he moves out from the confines of the fort into the swamp scenes and the ensuing battle at the Seminole camp. As I said earlier, his finest work would come a few years later but Seminole remains an entertaining little piece.

Now for the DVD. Seminole is available in R2 in the UK from Optimum and the transfer can best be described as weak. The picture is very soft and muddy throughout, and the colours are extremely faded – a real shame since this is a movie that would benefit enormously from strong, vibrant colours. The only bonus included is the theatrical trailer. There are editions of the film available from France and Germany but I have no idea if they look any better. All told, I would recommend the film – pity about the DVD.