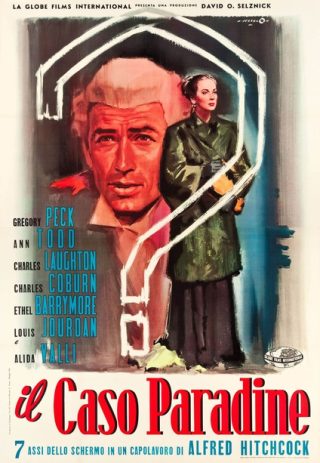

A Hitchcock film. This is a term which has become one of those key items of vocabulary common to all film fans. The director’s name is, I think it’s fair to say, universally recognized, which is no mean feat in itself when one remembers that he died over forty years ago and released his last feature a few years before that. In his lifetime and beyond the label “the master of suspense” was often applied, and it remains a fairly accurate descriptor. Is it a trifle restrictive though? Does it narrow the focus of his work too much? Perhaps. And perhaps it might be fairer, albeit admittedly lacking in poetry, zing, or just plain catchiness, to think of the Hitchcock film as a study of the moral dilemma. After all, his best works all present a range of ethical conundrums which both audiences and protagonists are tasked with navigating. While The Paradine Case (1947) is unlikely to figure in anyone’s list of best Hitchcock films, it does have some points of interest.

A beautiful young woman is accused of the murder of her blind husband and the barrister engaged to lead the defense becomes increasingly infatuated by her. That, in a nutshell, is the plot of The Paradine Case. By the time the film opens Colonel Paradine is dead. It feels somehow appropriate that a man who was unable to see, and whose life and death hold so much influence over the fate of the main characters, should himself remain unseen, save for the portrait which appears in the early scenes. As much as this is a Hitchcock film it is also a Selznick film and his presence hovers over proceedings just as the spirits of certain characters in his productions seemed to haunt others. If this is a theme affecting a number of Selznick pictures, it is perhaps understandable as the man himself appears to have been haunted by earlier successes and was so often looking over his shoulder at those ghosts of his own past in an effort to reclaim them. Although it is a very different movie, there is something of the aura of Rebecca to be found, as if the tendrils of mist drifting and curling around the drive approaching Manderley continue to cling. Some of that comes from the familiarity of aspects of Franz Waxman’s score and the set of Mrs Paradine’s bedroom in the country retreat looking a lot like that of Rebecca’s. The past is never far from these characters lives, it may be frequently referred to obliquely but is always there in the shadows.

Whatever one may or may not think about the myriad theories propounded by critics, observers and biographers over the years regarding Hitchcock himself, there is no question that the characters peopling his tales of suspense and crisis are beset by their own obsessions. In The Paradine Case Anthony Keane (Gregory Peck) is instantly bewitched by the cool, enigmatic beauty of his client. From the very first meeting he is entranced, his gaze fixed and his heart effortlessly purloined, the course of the case, his career and his marriage will be indelibly marked by the experience. It is an extraordinarily unsympathetic role though; the man is pompous and a prig, so dazzled by Mrs Paradine (Alida Valli) that he is both oblivious of how appalling his behavior is and staggeringly insensitive to how hurtful it is. We the viewers can see it in the awkwardness of those around him, in the uncomfortable pauses, in the cringing displays of petulance. Yet Keane himself sees none of it, he has in essence become the second blind man in Mrs Paradine’s life, morally if not physically sightless and wholly unaware of the emotional devastation his actions are wreaking.

The entire picture is of course dominated by another “blind” figure, that of justice herself standing aloof atop the Old Bailey, remote and apart from the desperate passions being enacted in the chambers below. Is justice finally served at the end of it all? The viewer can decide that; for my part, I think perhaps only partially so as the verdict returned is clearly correct but the “rightness” of certain other consequences brought about both before and after this is moot. The murder that sets the whole train of events in motion is really a variation on Hitchcock’s MacGuffin, being of the utmost importance to the characters on screen but of lesser significance to the audience. We are naturally interested in seeing how it will resolve itself, but I’d argue the answer is never in serious doubt and the greater interest is inspired by the personal and ethical crisis which Keane experiences and the way it unfolds (or maybe unravels might be a more accurate term under the circumstances) in a packed courtroom. Peck was quite young at this point but he seems to be playing older with the greying hair and vaunted reputation indicating a man approaching, if not already in, middle age. There are references made by his wife (Ann Todd) to the way he has changed since his idealistic youth and just about every action is suggestive of someone having a mid-life crisis, someone seeing cages and bars all around, besotted by the unattainable Mrs Paradine and driven jealous to the point of mania by what he regards as a younger rival in the shape of Louis Jourdan’s intense valet.

The eye of the storm throughout is Alida Valli’s unknowable widow. Her composure and control are remarkable and Lee Garmes uses his characteristic skill to light and photograph her striking features in such a way as to heighten this aspect. This makes it very clear how she is able to cast a spell over every man she encounters, but it also has the effect of distancing her too much – by the end she has been characterized as saint, sinner and demon all rolled into one but I don’t think much of that conveys itself to the audience in any meaningful way. The impression created of her as representing all things to all men is so strong that none of it feels authentic. In combination with Peck’s unsympathetic lead, this has the effect of creating a hollow at the heart of the picture. When a movie trades heavily on the emotional tides pulling and driving its characters this way and that, it amounts to a serious flaw.

Both Ann Todd and Louis Jourdan fare better, the latter as the wife who is at first bemused and then later steely and determined as she realizes that she has a fight on her hands. Hers is one of the more genuine performances in the movie, her role being easy to understand and drawing sympathy precisely because it is clear she wouldn’t dream of asking for it. One could say it is a very “British” performance, deriving power and feeling from its restraint. Louis Jourdan, on the other hand, simmers with self-disgust. He is a mass of conflicting emotions in and out of the witness box, anger, indignation and shame all call to him simultaneously before eventually consuming him.

Charles Laughton was an actor who could practically eat a film alive, and came awfully close to doing so in Jamaica Inn, his previous collaboration with Hitchcock. The Paradine Case gave him a smaller part, but a juicy one nonetheless and his sardonic and spiteful judge makes for an interesting comparison with the very different jurist he would essay for Billy Wilder a decade later in Witness for the Prosecution. Ethel Barrymore, playing his wife, turns in one of those fey, affected performances she was so adept at, clinging fearfully to the fraying threads of her own sanity. When she witters despairingly to her husband about how callous the years have made him it is hard not to imagine some foreshadowing of the path life has in store for Peck and Todd. Also among the supporting cast are Charles Coburn and Joan Tetzel as Peck’s solicitor friend and his coolly perceptive daughter. Finally, there are small parts for Hitchcock regulars Leo G Carroll and John Williams.

I am of the opinion that there is no genuinely bad Hitchcock film between The Man Who Knew Too Much in 1934 and Torn Curtain in 1966, while there are a number of undoubted classics as well as a few masterpieces in there. Sure some of the others are weaker and less successful and I’ll admit there are one or two which I do not like all that much. The Paradine Case is one of those frustratingly weak efforts. It looks sumptuous, has a superb cast and a premise brimming with potential. Yet the finished product is less than the sum of its parts and proves disappointing overall, failing to engage as fully as one would hope. Personally, I believe the blame can be placed on the writing – and Selznick seems to have been responsible for much of this – where the courtroom scenes are lacking in sparkle and snap and the portrayal of the leads saps all sympathy. In the final analysis, while it is certainly worth watching and has its moments this is a mediocre film that, had circumstances been slightly different, might have been a great one.