There are movies with strong openings, those which grab one’s attention from the very first shot and never relinquish their grasp thereafter. Others are slow burners, seemingly leading viewers down drifting, meandering paths till they finds themselves inveigled into the story in spite of themselves. Then of course there are the uneven affairs, movies which could be said to suffer from an identity crisis, confidently striking out in one direction before abandoning that plan entirely and gradually transforming themselves in a wholly unexpected manner. Three Violent People (1957) falls into that latter category, the broad beginning flirts and teases then segues into a lengthy middle section that lacks energy, before hitting the home straight with renewed vigor and purpose.

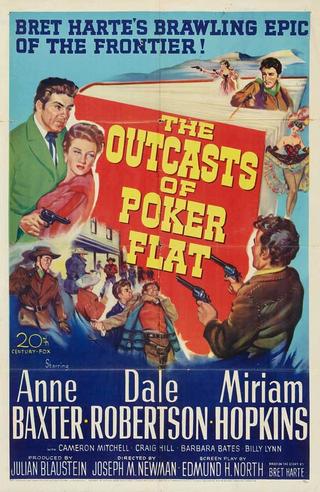

Colt Saunders (Charlton Heston) returns to Texas after the Civil War with three basic aims: to get his sprawling ranch back on a paying basis, to keep the grasping Carpetbaggers at arm’s length, and to find a woman to settle down with and make his wife. A brief dust-up with some of the aforementioned Carpetbaggers leaves him with a sore head, empty pockets and the strong suspicion that he’s just been rolled by newly arrived Lorna Hunter (Anne Baxter). She is one of those ladies discreetly referred to as “saloon girls”, though with a polished line in patter that creates the illusion of refinement and gentility. Her plan is to hook the well-to-do Captain Saunders and worry about the consequences of his finding out about her real past later. Well, she manages the first in record time and, not long after setting up home on the Saunders ranch, that deception does indeed come back to haunt her. In the meantime, Saunders finds himself butting heads with the crooked representative of the provisional government (Bruce Bennett) and his chief enforcer (Forrest Tucker).

Three Violent People was written by James Edward Grant and it is a very inconsistent picture. The opening suggests we’re in for a relatively light confection and both Baxter and Heston play it accordingly at that stage. However, as soon as they are married and the action moves to the ranch, the tone alters radically, not least with the introduction of Heston’s one-armed brother (Tom Tryon). It morphs into something that borders on the Shakespearean; guilt, retribution and envy all jostle for position as honor, decorum and the weight of expectation gaze broodingly from out of the past, and quite literally down from the portraits hanging sternly above the hearth. The ingredients here are certainly tempting, strongly spiced by the complication provided by Baxter’s pregnancy, while the machinations of Bennett and Tucker act as a savory side dish. Still and all, the end result is a stodgy concoction, that overstuffed middle proving to be a little too rich. The last act saves it somewhat – a face-off timed by an upturned whiskey decanter, a brisk yet gratifying duel, and a wrap-up that blends vindication and personal growth.

Three Violent People wouldn’t rank as Charlton Heston’s best role in westerns, but he still does what he can with it. He had a knack for walking that line between pride and implacable priggishness. That emotional puritanism is given a good run-out here and collides headlong with the natural compassion that arises from the plight that Baxter finds herself facing. As he finds almost everyone turning against him, he starts to unbend emotionally and morally and manages to redeem himself in the end. Baxter is fine as the woman looking for a way out in life, taking the kind of rash decision that fits the feisty and mischievous woman we first encounter and then finding that she has the requisite steel within when her deception is dragged out into the light.

Tom Tryon, an actor I’ve never been that keen on excepting a good enough turn in Preminger’s In Harm’s Way, is much less effective as the maimed brother. His role is poorly defined, there is resentment there, as one would expect, and bitterness too. However, his demeanor is a little too glib and arch and it’s difficult to get a handle on his real motives. It doesn’t help either that his character’s disability looks hugely unconvincing – just like a man wearing a large and bulky sling under his shirt. Forrest Tucker is reliably mean as the hired gun, conniving and blustering in his characteristic style. One of the real standout performances, however, comes from Gilbert Roland as Heston’s foreman. I don’t believe I’ve ever seen Roland give a bad performance and his role in Three Violent People offers ample opportunity to display his unique style, that suave, man of the world wisdom and shrewdness. He brings a touch of grandness to the part, offering Heston’s stiff prude an object lesson in dignity and true honor in one of the key scenes late in the movie as he disdains a tainted toast following the birth of his employer’s child. It is a terrific moment and Heston’s stung and startled countenance as the man he has esteemed all his life excoriates his pompous moralizing is something to behold. It is his holding up of a mirror to Heston’s sanctimony that sets the character on the road to salvation. In support, Bruce Bennett is a bit colorless and lacks bite, while Jamie Farr (who I will always think of as Klinger from MASH) and the controversial and recently deceased Robert Blake both appear as sons of Gilbert Roland.

The movie was released on DVD by Paramount many years ago and the widescreen transfer looks acceptable, but maybe not a strong as some of the studio’s other titles do. Generally, I am fond of the films of Rudolph Maté, but Three Violent People is a weaker effort. It’s not a bad film, and I certainly hope I haven’t slated it here, but it is not all it might have been either. The writing needed to be tighter and some of the internal conflict lacks the punch it ought to have. This, in conjunction with some rather lackluster work from Tom Tryon in a pivotal role, diminishes the overall effect of the production.