Every story takes its characters on a journey, and invites the viewer along for company too of course. Those narrative journeys must bring the protagonists to some new place in life, another staging post from which they can embark on the next leg of wherever it is fate or destiny has offered up as a choice. It’s not always a literal journey, one involving actual travel from point A to point B, but it sometimes is and that sense of real physical movement can he a handy way to highlight the more important shifts that occur. The Tall Men (1955) is what we might call a trail drive western from one of the pioneers of the form; Raoul Walsh had directed the impressive and innovative The Big Trail a quarter of century before and there’s even a nod toward that production in the lowering of covered wagons on ropes down a sheer cliff face at one point. In pursuit of dreams that are both competing and complementary, Walsh takes his characters up and down the length of the United States, and even further than that emotionally.

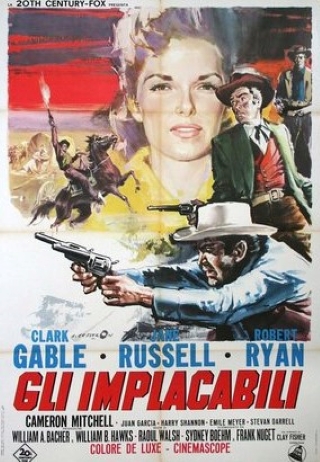

It opens in the snow, a chill and bleak backdrop with the color drawn out and starkness and bleakness to the fore once the blood red credits have faded from the screen. It is 1866 and the aftermath of years of conflict has left some men cast adrift, men such as Ben Allison (Clark Gable) and his younger brother Clint (Cameron Mitchell). That beginning deftly informs the viewer of the cynical and detached perspective of the lead characters – the sight of a hanged corpse in the wilderness prompting a throwaway line about civilization that is ripe with bitterness. Yet Walsh was not a cynic, he was at heart a romantic (even if he might never have wanted to admit that in public) and his best movies all set his characters off on grail quests for the truth and fulfillment that they must ultimately find within themselves. Ben Allison and his brother seem to be searching for nothing more than quick and easy money at the outset, staking out and executing a cheap and tawdry bit of banditry when they hold up and abduct a man they figure is both moneyed and green. That man is Nathan Stark (Robert Ryan), and while he may be carrying plenty of crisp new banknotes, he’s far from being a fool. He wrong-foots the brothers by offering them not a date with the law but a business proposal – help him drive a herd of cattle from Texas all the way up to Montana and share in the profits on completion. For men who are not by nature thieves, this offers them a way out, a chance to step away from the tantalizing vortex of crime and a life outside the law before it is too late. Setting out on that long ride back south to assemble a herd is the first step, and it also brings about a meeting with the other central character Nella Turner (Jane Russell), the woman who will bind all of them together and who prompts a reassessment among them of what they want and where they want to be in life.

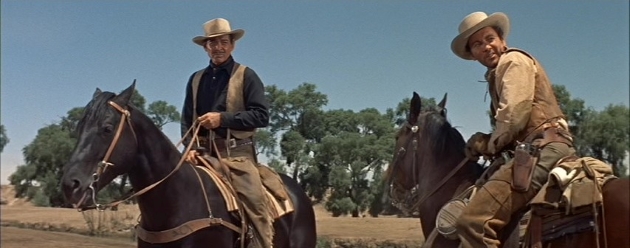

The Tall Men was the first time Raoul Walsh worked with Gable, Russell and Ryan, and he would go on to make The King and Four Queens and Band of Angels with Gable, and The Revolt of Mamie Stover with Russell. There are many who would characterize Walsh’s filmmaking in terms of action and movement, and there is certainly plenty of that on display in The Tall Men. The sense of forward momentum, aided by the driving nature of the plot, is never far from the surface. Those action scenes, the seeing off of the Jayhawkers and the climatic stampede are shot and marshaled with considerable aplomb. Still, it is some of the quieter, more intimate moments that raise the movie and make it more than a simple shoot-em-up in the wilderness. The early scenes, after Gable has rescued Russell and they find themselves sheltering in an abandoned cabin, have great warmth and set the characters up for the developments that will follow. Gable and Russell form the core of the movie, the characters growing and changing in a way that feels very natural and the course of their relationship is first mapped out in that cabin sequence.

The use of music in this movie is artful and crafty too in the way the song – that vague ribaldry of the lyrics is characteristic of Walsh’s sense of humor – Russell sings, and appears to improvise according to circumstances, charts the peaks and troughs of her relationship with Gable. It’s not the first time a song has been used to punctuate a western, but it does feel different in the way its fluid lyrics alter depending on the singer’s mood while the theme itself remains constant.

“There goes the only man I ever respected. He’s what every boy thinks he’s going to be when he grows up and wishes he had been when he’s an old man.”

That line is uttered near the end by Robert Ryan’s Nathan Stark of Gable and it feels like screenwriters Sydney Boehm and Frank Nugent had the star himself in mind when they came up with it. The ageing Gable is used to good effect once more, that weariness that came along with the years, as well as the wisdom and philosophical self-awareness that is always lurking nearby, help to create a character who feels real, one whom the viewer can relate to and root for. Russell plays off him nicely, their moments together indicate chemistry and her role is of course key to making the plot work. Without her provocative and heartfelt performance the destination Gable, and Ryan too, arrives at would have little meaning.

Robert Ryan was one of the true masters of ambiguity, his heroes exhibiting bumps and cracks in their surface smoothness and his villains typically suggesting some grain of decency even if one would have to dig deep to find it. His Nathan Stark is a complex and nuanced portrayal, almost obsessively ambitious and capable of flat out ruthlessness, but he has a style about him, a kind of honest worldliness that is hard to resist. Once again, the script does the character justice, allowing the arc described to follow a natural path and, in the end, to reach a very satisfying destination. Cameron Mitchell was in the middle of a pretty good run at this time. Always more of a strong supporting actor than a natural lead, he had a knack for conveying callowness and occasionally suspect judgement. There is a point along the trail where it looks as though he may be heading down a disappointingly predictable route but the writing draws him back from that and his own skills make the turnaround credible.

The Tall Men has long been available on DVD, and it has always looked very nice too. The movie got a Blu-ray release in the US from Twilight Time and one in Germany via Koch Media, both of which are now out of print. Being a Fox title and therefore now owned by Disney, I guess hopes of a reissue on BD are slim at the moment. The movie is another of those classy pieces of filmmaking by Raoul Walsh which can be approached as both a slick entertainment package and also as a subtle commentary on the compromises people need to make if personal fulfillment is to be achieved. All told, a really fine bit of cinema.