“People have funny things swimming around inside of them. Don’t you ever wonder what they are?”

It’s odd the way casual, essentially throwaway pieces of dialogue have a habit of penetrating right to the core of the issue. Good dramatic writing will always seek to discover how and why people react to certain circumstances, certain stimuli. In melodrama, those reactions are by necessity heightened and may appear nonsensical or even contradictory when viewed with a cool, detached eye. Yet these contradictions and intensities are actually what validates the melodrama, the heightened feelings serving to draw all the illogicality of life itself into sharper relief. Fritz Lang’s Clash by Night (1952) is an example of a successful blend of film noir and melodrama in this adaptation of Clifford Odets’ play.

Mae Doyle (Barbara Stanwyck) is back home, back in Monterey after a decade in New York and points east, dressed up in disenchantment and drinking whisky for breakfast. She had been a dreamer once, setting out eagerly in search of her personal pot of gold labeled fulfillment. Time and disappointment have taken their toll though, leaving Mae long on regret and short on options. In fact, the only door remaining open to her, and it’s no more than ajar at best, is the one of the home she grew up in and then ran away from. Her younger brother (Keith Andes) offers a grudging welcome but there’s interest stirring in other quarters. Jerry D’Amato (Paul Douglas) is a fisherman, and her brother’s employer, all muscle and heart, and quickly smitten by Mae. However, there is bound to be a fly in the ointment and this one turns up in the shape of Jerry’s friend Earl Pfeiffer (Robert Ryan). Where Jerry is clumsy in his simplicity, Earl is brash and overbearing. Crucially though, his is a restless spirit, one which is drawn irresistibly to Mae, but she professes to be unimpressed by his shallow braggadocio and instead accepts Jerry’s heartfelt proposal. Nevertheless, just as those massive seas mercilessly pounding the coastline in the opening credits have foreshadowed, great emotional tumult lies ahead.

Film noir trades heavily on disillusionment, detachment and the ever-present threat of despair. Clash by Night taps into all of these, most especially a kind of gut wrenching disappointment and the awful sliding sense that all the positive things life might have to offer will forever remain just beyond reach. It’s like a head-on collision of post-war ennui and middle-aged malaise. Even as the protagonists sweat and struggle in the balmy atmosphere, on a personal level the first chills of autumn are already making themselves felt. I’ve no doubt the disenchantment and uncertainty over what direction to take in life would have struck a chord with a contemporary audience less than a decade after the end of a major global conflict, but the movie has a relevance beyond those immediate concerns. The idea that one can be tempted and seduced by superficiality isn’t confined to any particular era after all. At first, the material might seem atypical for Fritz Lang, but the idea of individuals trapped or restricted by (poor) choices and circumstances is entirely in keeping with his other work. Nobody is really free in this movie – even those who would have us believe they are free spirits are just as hemmed as everyone else – and practically everybody is straining against their respective bonds. Visually, Lang and cinematographer Nicholas Musuraca impress on the audience the claustrophobia felt by the characters first in Mae’s family home and then later in Jerry’s house, both of which are slightly elevated and therefore have a sense of remoteness about them. Consistent with the overall tone of the piece, however, there is at least a suggestion of an out, of an escape from the stifling ties that bind in the occasional shots of a moonlit sky or indeed of the vast ocean.

The casting works well, a trio of forty-something actors in the principal roles have that combination of a vaguely shopworn air, a burgeoning realization that time is not on their side, and enough of a spark and appetite for living to make their desperate snatching at the half chances flitting by appear credible. Robert Ryan always seemed to be the epitome of edgy, his characters existing on the periphery of society and civilization, like an interloper in his own home. Earl Pfeiffer is boastful, abusive and bullying; it is impossible to like a man who builds himself up by bawling out put upon waiters or forcing himself on women, but Ryan’s skill lay in his ability to add layers and dimensions to such boors, and his frustration at and awareness of his own flaws fleshes out the character and dismisses the caricature. Stanwyck is every bit as versatile in her own way, moving from pride to defiance, bitterness to fear, and all the time grounded by a frank admission of her character’s own weakness. Her role is both defined by her interactions with Ryan and Douglas and simultaneously creates a meaning and motivation for those two co-stars.

“Don’t say anything. Don’t make no promises. I’d have to trust you, that’s what the terrible thing is. You’ve got to trust somebody, there ain’t no other way.”

When Paul Douglas utters those lines right at the end of the movie there’s no doubting the essential truth of the words, for Jerry D’Amato and for the audience at large. This, coupled with the notion that a form of redemption could be attained by confronting and acknowledging the less savory aspects a person carries within, hints that the fatalism commonly regarded as being irrevocably wed to film noir may not be entirely insurmountable. Paul Douglas’ portrayal of non-judgmental decency, unbowed before loneliness and betrayal, is key to making this work. His scenes with Stanwyck range from the supercharged and fiery to the downright mundane, and the climactic one strikes a satisfyingly hopeful if not quite happy note. For all that, the one which lingers longest in my memory is an earlier interlude aboard his boat. He’s proposing, all awkward and shambling earnestness, and she’s resisting. There is some terrific screen acting on display from those two in that moonlit sequence, a pair of fine performers affording a glimpse of people teetering on the brink of temptation and trepidation. A magical moment of cinema.

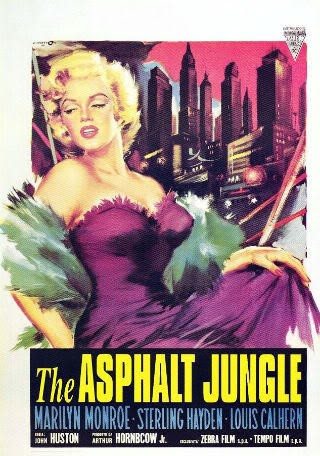

While the three heavyweights in the leading roles naturally dominate proceedings, there is depth further down the cast list too. Marilyn Monroe was a rising star, just a year away from breaking through to the very top tier, and was billed fourth, just above the title. Even though she’s not the focus of attention she does get a few moderately memorable scenes, mostly sparring with a surly Keith Andes. This young couple are prey to some of that restiveness that plagues their elders; the shifting dynamics of post-war relationships, that realignment of social mores and roles, suggest that there is likely to be a good deal of friction, or even worse, ahead. J Carrol Naish was one of the most accomplished character actors of the classic Hollywood era, an instantly recognizable presence. As the wastrel Uncle Vince he occupies a small yet pivotal role, a Iago-like hobgoblin sowing unrest out of spite and whispering poison in his nephew’s ear at every opportunity.

Clash by Night was released on DVD long ago by Warner Brothers but I think it may have drifted out of print. It’s a pretty good transfer of the movie, and has a Peter Bogdanovich commentary track as a supplement, but any future upgrade to Blu-ray would be welcome. Fans of Lang’s work, and that of the leading players too, should find this an absorbing movie. It certainly earns a recommendation from this viewer.