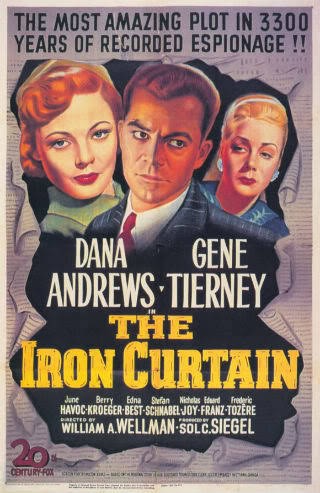

The 50s saw the red scare, fanned by McCarthyite rhetoric, blaze into life in Hollywood. With the HUAC inspired blacklists casting a dark pall over the movie capital, there was a kind of desperation in the air, a need to prove one’s patriotism and simultaneous rejection of the evils of communism. This meant the decade saw the production of a number of films directly addressing the issue and sending out a message to the witch-hunters that the industry was aware and prepared to play ball. Whatever contemporary reactions may have been, these films, by and large, not only seem lousy when viewed today but they also remind us of all those careers and lives left in tatters by the taint of the blacklist. From a purely artistic standpoint, the ham-fisted presentation of political dogma and the judgemental tone adopted both bog down the narrative and, in the worst cases, leave a very sour taste. However, there are always exceptions, and William Wellman’s The Iron Curtain (1948) is one of the more polished and less hysterical pieces of work from a generally unsavoury interlude in cinema history. I think this is partly due to the skills of Wellman as a filmmaker, and partly as a result of the production taking place right at the beginning of HUAC’s reign of terror, before it’s raging paranoia had fully matured.

In keeping with a lot of Fox movies of the time, the film opens with a declaration that what we’re about to see is a true story, shot on real locations. The cool, authoritative tone of the narrator further enhances the sense that this is something more than mere Hollywood fantasy. I’ve often found that there’s a tiresome quality to some of these earnest eulogies to the dedication and responsibility of various government agencies remaining ever vigilant in the face of multiple threats from without and within. What sets the introduction of The Iron Curtain apart is its location if nothing else. The entire film takes place in Ottawa, Canada, so we are spared yet another hymn to the efficacy of the FBI, Treasury agents or other assorted G Men. Instead, the plot follows the establishment of a Soviet fifth column in Canada during the war and its subsequent dismantling as the big freeze of the Cold War set in. As I said, the movie doesn’t takes us behind the scenes of one of those complex government sting operations that were much favoured by contemporary filmmakers, but concentrates on telling the tale of how one man brought a spy ring to its knees off his own bat. The man in question is Igor Gouzenko (Dana Andrews), a cipher clerk freshly assigned to the Soviet embassy in Canada. The first third of the film goes to great pains to establish how loyal Gouzenko was to his own country and political system, one of those resolute, unthinking servants of the state with clear and direct convictions. As we observe the steadfast Gouzenko going manfully about his duties, we’re also afforded a view into the closed world of the Soviet diplomatic mission. And it’s a drab, forbidding world at that, peopled with stony-faced officials and dripping an atmosphere of suspicion and secrecy. There’s also a glimpse at the careful construction of the spy network, whose eventual unravelling provides the dramatic backdrop for the latter stages of the story. It’s Gouzenko who brings the whole thing crashing down, and his motivation for doing so is a slow realization that he’s serving a flawed master. The catalyst for his decision is the arrival in Canada of his wife Anna (Gene Tierney), and the birth of a son. The presence of this human element greatly strengthens the story and adds to the dramatic tension of the final third. By doing so, the political aspects necessarily take a back seat to the unfolding drama of a family suddenly cast into a perilous situation.

Even if it’s viewed purely as a propaganda piece, then I think The Iron Curtain is remarkably successful. The reason for that is the script and Wellman’s ability to sidestep the trap of sensationalism and instead adopt a more matter of fact tone, letting the events and their inherent drama speak for themselves. Of course, the air of quiet dread that seems to hang over the scenes in the embassy emphasises the stifling lack of personal and intellectual freedom, but this is quite subtly achieved. The ever-present music from Soviet composers, the inclusion of which in the score apparently caused something of a minor international incident at the time, has the effect of building up the brooding, sinister feel. The only time we take a detour into the realm of direct political preaching is when one of the Soviet residents (Eduard Franz) seals his own fate by getting drunk and lamenting the betrayal of the ideals of the revolution by the apparatchiks who have risen to prominence in Moscow. As a thriller, the film really comes into its own in the final third, as Gouzenko decides to take that leap of faith and defect. Wellman, and cameraman Charles G Clarke, employ classic film noir techniques of lighting and shooting angles to ratchet up the tension during Gouzenko’s theft of incriminating documents from the embassy, and then again in the climactic standoff in his apartment. Another notable aspect of the film is how the government agencies – I’m guessing the Canadian setting facilitated this slight subversion – are conspicuous by their lack of involvement. In fact, there’s initially a downright refusal on the part of the authorities to become involved in what they take to be the ravings of a lunatic.

Dana Andrews was never one of the most emotive or demonstrative of actors, the kind of guy who tended to keep it all inside and bottled up. Such characteristics can unfairly lead to accusations of woodenness when the truth is it’s simply another, and no less effective, style of performing. As it happens, that tight-lipped anxiety that he had a talent for fits the character of Gouzenko to a tee. After all, this is a man who’s been trained to exert self-control in the first place and who then finds himself in a situation where both his own and his family’s survival depends on the maintenance of a facade. Still, Andrews conveyed more than a blank countenance when he had to, the eyes in particular registering the mounting pressure Gouzenko was subjected to. Gene Tierney was making her fourth film alongside Andrews, the most successful being their partnership in Laura a few years earlier, and was good enough in a fairly undemanding role. Her main purpose was to act as a softening and humanizing influence on her previously stiff and determined husband, and that’s how she comes across. However, arguably the most memorable work is produced by the supporting cast. Berry Kroeger was making his screen debut as the shadowy head of Canada’s communists and carries off the part of the principal villain with aplomb. Playing such a Machiavellian puppet master required a good deal of restraint combined with implicit menace. Kroeger was blessed with the features and voice that were ideally suited to this kind of role and he makes a very strong impression. Stefan Schnabel also shines as the head of the NKVD, masking a dangerous ruthlessness with an outwardly reasonable persona. And finally, June Havoc appears as the embassy secretary with a wandering eye and a special brief to vet the reliability of all new staff.

I think the only DVD edition of The Iron Curtain to date is the one issued in Spain by Fox/Impulso. In terms of picture quality, it’s one of their mid-range efforts. There hasn’t been any restoration work done, as can be seen from the cue blips and so on, but the print used is in generally good condition and doesn’t display noticeable wear. Extras are limited to the usual gallery and text data on the cast and crew. The disc offers English and Spanish soundtracks – the Spanish subtitles are optional and can be deselected via the setup menu. While I certainly don’t think this film represents Wellman at his best, it is an interesting addition to his body of work. The main attraction of The Iron Curtain though lies in its historical significance, coming as it does near the beginning of the red scare. It’s interesting to observe the comparatively restrained approach it takes to its emotive subject matter in contrast to some of the more hyperbolic and offensive offerings that the following decade would eventually produce. Generally, this is worthwhile viewing for fans of Wellman and for providing a snapshot of early Hollywood reactions to the HUAC assault.

![£38]](https://livius1.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/02/c2a338.jpg?w=676)