Without having initially planned to do so, I ended up watching a selection of movies directed by Alfred Hitchcock all through September. I tried to choose those titles I had not seen for quite some time and have been jotting down and recording my thoughts on each in brief as I’ve gone along. Having done so, I figured I might as well assemble them here as an end of month round-up. So here goes:

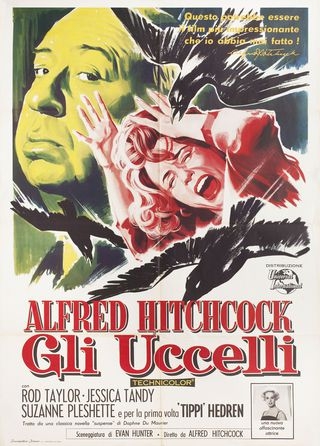

The Birds (1963)

It’s been many years since I last watched this and I’d forgotten just how well constructed it is, not to mention its technical proficiency bearing in mind the era.

That long, slow build-up is the work of a deeply confident filmmaker. It’s never boring or tedious and the gradual, estrogen-fueled tension, with all the cats among the pigeons, is drawn ever tighter in tiny but finely judged increments. When the full chaos is finally unleashed in the apocalyptic latter half Rod Taylor does get to flex bit of muscle, literally and figuratively.

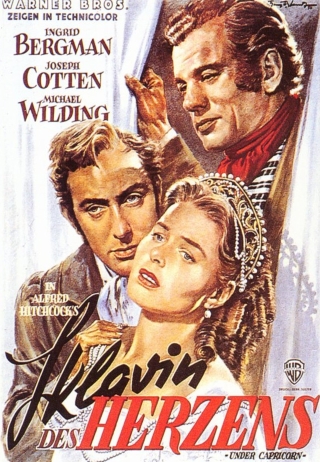

Under Capricorn (1949)

Very much lesser Hitchcock, a movie which barely anyone ever has a good word to say for. Well, I’ll at least say that it is handsomely shot, courtesy of Jack Cardiff, and the acting is fine even if Michael Wilding does lay the whimsy on with a trowel at times.

But yes, it is a problematic movie. And that is largely because it tells a story which is thin, not uninteresting in itself but too thin for its running time. It needed to be trimmed and compressed, which would have been hard to do because of the other great flaw – the director’s insistence at the time on experimenting with long takes. It hamstrung the previous year’s Rope (though that one has other issues dragging it down too) and was a technique that was antithetical to Hitchcock’s style.

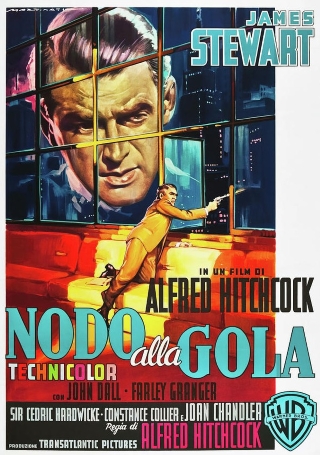

Rope (1948)

I’ve never especially liked this. The technical ambition is admirable, and I’ve always been somewhat hypnotized by the seamless skill involved in the gradual change in the lighting of the studio bound skyline as the tale unfolds in real time. However, the whole continuous take conceit imposes huge limitations on the cast and crew and the process must have been a genuine pain for everyone involved. As with Under Capricorn, the entire business works to undermine the director’s natural strengths.

The biggest problem I have with the movie though is the coldness and indeed the malice at its core. Nobody aside from Cedric Hardwicke’s anxious and compassionate father comes out of it well. That’s not to say it’s badly played of course. Granger could do that weak sister act with his eyes closed and Dall has the clinical and supercilious aspects down pat too – he always seemed to manage that though and there’s a hint of that inherent unlikeability also found in Laurence Harvey in all his parts. James Stewart nails the creeping suspicion that blossoms into horror and then outrage and (self?) disgust. But his character is not really sympathetic either – a man of his intelligence ought to have realized the kind of seeds his intellectual posing was planting.

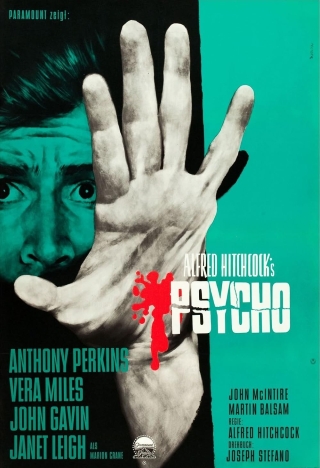

Psycho (1960)

It’s probably 15 years, maybe even more, since I last watched this. The first half always worked best for me and I still feel the same. The paranoia and gnawing guilt of Janet Leigh’s Marion is perfectly encapsulated in the minimalist style of that whole opening section – the rain, the ever more frantic musing, Herrmann’s nervy score and those seemingly permanent close ups of Leigh’s huge, expressive eyes.

And then there’s that frankly sublime sequence in the motel cabin. Cagey and uncomfortable, pathetically flirtatious and taut all at the same time. I reckon it’s the best scene in the entire movie. What follows in the last hour engages me less. It remains visually astounding and technically flawless, but too much of the artful subtlety drains away with the bath water. It still grips and shocks at times, just much more conventionally and it never again approaches the emotional precipice that was teased by the interaction amid stuffed birds, sandwiches and milk.

Nevertheless, it is still undeniably a great piece of cinema, the heights approached and attained in that first hour and the total assurance of a director genuinely in love with his medium are enough to ensure that.

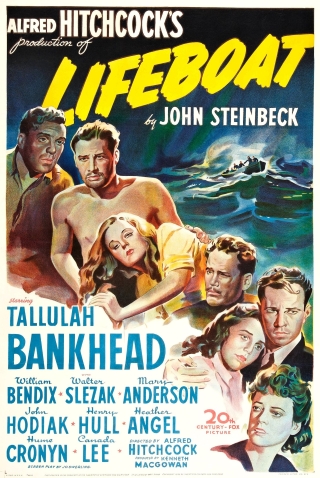

Lifeboat (1944)

A wartime propaganda picture from Hitchcock. Still, being a Hitchcock movie there’s more to it than that – by a circuitous route it winds up as something of a celebration of cohesiveness. Just about every stratum of western society is represented, from Henry Hull’s super rich kingpin to John Hodiak’s blue collar revolutionary, from the stoicism of Canada Lee to the louche decadence of Tallulah Bankhead. All the disparate characters are by turns gulled, threatened and finally drawn together by the malignant presence of Walter Slezak’s cool and cunning Nazi.

It’s another of the director’s challenges to himself, an exercise in the potential of confinement that makes up for in intensity what it arguably lacks in suspense. Alongside the more eye-catching dramatics of those further up the cast list, it’s satisfying to watch the slow development of a gentle romance between fairly regular Hitchcock collaborator Hume Cronyn and Mary Anderson, an actress who never much graduated beyond supporting roles except perhaps in the rarely seen but rather good Chicago Calling.

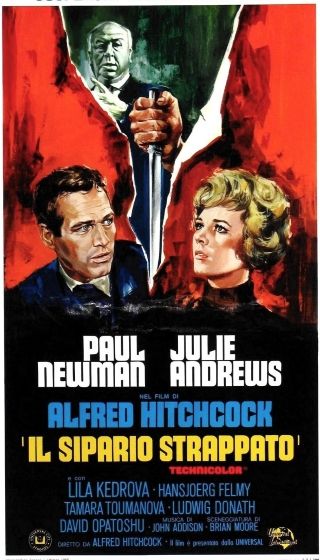

Torn Curtain (1966)

This is the point at which Hitchcock’s decline can be discerned. This Cold War thriller starts out as a double-cross drama where the bluff is drawn out too long before turning into a more successful cross-country chase, the kind of affair Hitchcock could make with his eyes closed.

The first half of the movie misses more than it hits, the brief bookstore scene in Copenhagen errs just on the right side of oddness, but the drab grey/green palate when events move to East Germany reflects the dullness of much of that section, not helped by a listless and detached performance by Paul Newman and an uncomfortable looking Julie Andrews. Some of it does work though – I like the entire build up to the farmhouse scene where the Stasi spook Gromek is laboriously disposed of, and Ludwig Donath is spikily entertaining as a caricatured professor.

The bus ride/pursuit has its moments, helped by John Addison’s slightly eccentric score and an earnest David Opatoshu. There are a few late flourishes too – the hiding among a crowd/creating a distraction ploy is revisited for at least the fourth time – off the top of my head variations thereof are employed in The 39 Steps, Saboteur and North By Northwest if not more.

So, a mixed bag all told. I guess it does more wrong than it does right yet I’ve always had a greater fondness for it than it probably deserves.