I’m going to have to confess that I’ve drifted away from contemporary Sci-Fi movies, or maybe they have drifted away from me. It’s a tricky genre in many respects; there is the obvious need to make movies that entertain, but in order to rise above mere popcorn fare it is necessary to have a story underpinning it all that asks questions or offers ideas for consideration. Now one could say that this applies to all genres and I’d tend to agree. Yet what sets Sci-Fi apart is the fact its inherent inventiveness and malleable boundaries allow for a more enticing examination of themes that might appear dull if presented in other genres. I guess it boils down to the need to strike a balance between the entertaining and thought-provoking aspects.

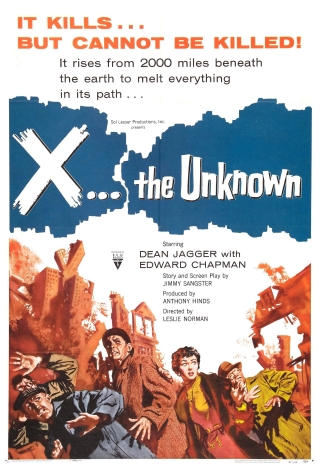

Growing up, I was entranced by classic Sci-Fi, and the entertainment quotient was what grabbed my attention back then. Later, I came to appreciate the way that many of these movies wove social and philosophical commentary in among the thrills. Of course filmmaking has changed a lot over the years, and the visual effects that enhance and enrich the wondrous nature of Sci-Fi have advanced impressively. Sometimes I think that this huge improvement also conceals behind its cloak of digital magic the seeds of my gradual dissociation from the genre. Has the balance shifted a little too sharply, and has the superabundance of visually startling imagery and whizz-bang effects obscured some of the thoughtfulness that once characterized the best of the genre? I found myself wondering about such things as I watched Hammer’s X the Unknown (1956) the other day, the type of cheaply made movie that fascinated my younger self, and still does in fact.

Paranoia fueled so many of the great classic era Sci-Fi movies with the concept of the enemy within growing out of the Cold War and the fears and misunderstandings that accompanied it. Often the enemy within was presented as an infiltration of society, either on an individual or communal level. X the Unknown takes a different path, one leading not to the heart of mankind but to the heart of our planet itself with the implication that our greatest threat comes not only from a fatalistic and seemingly unstoppable force of nature, but one which has been festering away deep below the surface, practically written into the DNA of our world. It’s a fine idea in itself and the execution offers a lesson in how to extract as much suspense and implied horror as possible on a shoestring. It all begins during a tiresomely routine military exercise, the random placement of a mildly radioactive object causing the sudden appearance of a mysterious fissure and the consequent death and destruction that is unleashed. The frequency of fatal encounters with whatever broke free of that fissure gradually picks up pace and even leads to the leveling of that old charge that scientific tinkering and dabbling lies at the root of it all. That notion, happily, is given short shrift, dismissed almost the moment it is uttered and both challenged and disproved by the close. I have an unpleasant feeling though that were this movie to be remade today, in a climate where quackery is all too often hailed while science is belittled, the reverse might actually be the case.

In all honesty, however, I don’t see how a movie like this would be made at all nowadays. The cast is almost exclusively male and middle-aged at that. There is nothing remotely glamorous about leads such as Dean Jagger and Leo McKern, but what they do bring is a sense of calm authority and a reassuring coziness (and I use that term without any pejorative undertones) amid all the mayhem. The source of the danger is kept out of sight for most of the running time, only glimpsed very briefly before the one hour mark and sparingly and sporadically thereafter. It works on the principle that what exists in the mind’s eye is apt to be more unsettling than full exposure to creaky effects. A modern version would feel obliged to conjure up and highlight some effect that would undoubtedly dazzle yet would also be less likely to capture the suspense that comes from dread unseen.

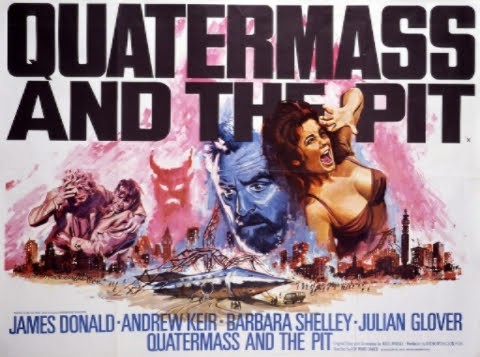

Hammer had just made and enjoyed success with their version of Nigel Kneale’s The Quatermass Xperiment and so were looking to capitalize on that with a follow up. Kneale appears to have objected to the name of his lead scientist being used and so Jimmy Sangster’s script has Adam Royston rather than Bernard Quatermass desperately seeking a way to battle the terror seeping from the Earth. Had Kneale been involved, it seems likely the plot would have involved some kind of alien presence or interference. That would undoubtedly have been a literate and intelligent approach, but I have to say I rather like the fact that what we got is a wholly terrestrial and primal threat – somehow the notion of danger emanating from that which we know best and which is dearest to us adds an attractive twist to it all. If you’ll forgive the pun, it serves to ground the story. While I wouldn’t quite categorize it as an early Eco-thriller, it does raise questions about our symbiotic relationship with the planet itself. Leslie Norman directs efficiently and briskly enough, though it is tempting to wonder how it might have turned out had first choice Joseph Losey not dropped out. It has been said that the blacklisted Losey was removed at the insistence of Jagger, but there are also claims that it was actually down to a health problem suffered by the director.

X the Unknown was given a Blu-ray release in the US back in 2020. I’ve only seen some images from that version and they look appealing, sharp and in a 1.75:1 ratio. My own copy is a long out of print UK DVD that appears to be open matte. While it won’t have the crispness of the BD, it’s not a bad effort and, in my opinion anyway, remains perfectly watchable. This is the kind of Sci-Fi I adore, modest in scale yet expansive enough in vision and imagination to override its technical limitations.