The simplest stories can sometimes be the most absorbing. Having just spent a very rewarding hour and a half viewing Time Lock (1957), I reckon it would also be fair to say such films can be among the most suspenseful too. In this case it really is down to the quality of the story itself. The budget must have been slight, the cast is limited and has no especially big names, and the direction is not particularly showy. However, the subject matter is such that it grabs the attention and then holds it in a steely grip right up to the moment the end credits roll.

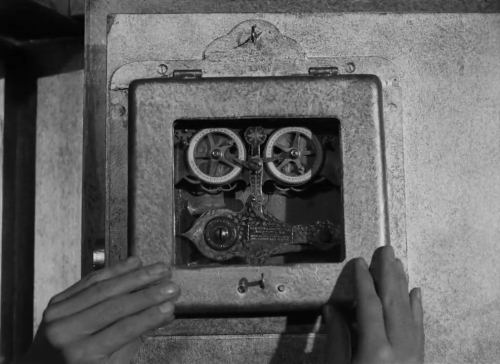

Toronto on a sleepy Friday afternoon in the middle of July. It’s a time when most people will be thinking of the days ahead, pleased to have left the trials and pressures of another working week behind them. In a sense, all the danger signs are present in that period of time, a soporific blend of relief at what’s been relegated to the past and anticipation for what the future may hold leading to casualness or indeed carelessness in the present. It should come as no surprise then that the arrival of Lucille Walker (Betty McDowall) at the bank where her husband Colin (Lee Patterson) works is accompanied by a degree of laxness on the part of everyone there. Pretty much all of the staff, the manager (Alan Gifford) included has at least half an eye on something other than work. It’s also the Walkers son’s sixth birthday and he’s naturally being treated with even more indulgence than usual. As he scampers around the bank clutching his new flashlight and seeking out various nooks and crannies to test its effectiveness, there is the sound of a collision on the street outside. It draws the attention of everyone, even the manager and Colin Walker, who are in the process of setting the time lock on the vault. A quick glance through the windows shows that nothing serious has occurred, not outside anyway. And then the vault door is swung shut and the locks activated. Just as the heavy, unyielding steel seals itself, an even heavier realization descends on those in the bank – the boy is nowhere to be seen, and has clearly been shut up tight in a strongroom that cannot be opened till Monday morning. Disbelief is soon shooed aside by panic, which in turn finds itself chased away by a gnawing sense of desperation. The air supply is finite, the vault virtually impenetrable, and the only man who might know how to get in (Robert Beatty) is off for a weekend of fishing.

It’s a very simple and uncomplicated story, a small boy trapped in a vault and a race against time to free him. However, it is the simplicity that makes it work so well. It is a situation that is both unthinkable yet also entirely credible. These two factors add an edge to the suspense that grows naturally from any race against the clock tale. At first, I was a little surprised to see that the script was derived from a play by Arthur Hailey. There is the temptation to see his bestselling novels and their adaptations for the big and small screen as large scale, sprawling affairs – Airport and Hotel certainly spring to mind. Yet even those are quite contained in a sense, and there’s no getting away from the fact that his subject matter favored scenarios where unexpected drama was wrought from essentially mundane circumstances.

Perhaps more surprising is the production team behind Time Lock. When the credits announce that the feature is directed by Gerald Thomas and written and produced by Peter Rogers, well one would be forgiven for jumping to the conclusion that a ribald comedy was on the cards. After all, those two were responsible for the long running Carry On series of movies. You’d never know that from a viewing of this film though, the tone remaining deadly serious all the way through as befits such a tense premise.

Looked at from today’s perspective, the movie had one big star – Sean Connery. However, this was right at the start of his career and his role is small, as one of the workmen called in to see if there was any chance of their oxyacetylene cutting gear making an impression on the vault door. The main parts are filled by Lee Patterson and Betty McDowall as the helpless parents who are unable to anything other than wait and hope and pray. Alan Gifford, who shared the screen with Patterson the same year in the rather good The Flying Scot, gets a reasonably juicy part as the guilt-ridden bank manager. Robert Beatty heads the cast, even though he only enters proceedings about half way through, as the expert on safes. When he does appear he ushers in a sense of even greater urgency, brisk and brusque in his management of a situation whose margins of error have by then been shaved right down to the bone.

I don’t think Time Lock has ever had a DVD release in the UK, although it has appeared in the US, included in one of Kino’s British Noir sets, and in Australia in the past. It would have been a good title for Network’s British Film line, but the company’s sad and sudden demise means that will never happen now. Anyway, it remains a terrific little suspense yarn that manages to do a lot with limited resources. I definitely recommend the film to anyone who is not yet familiar with it.