No, not The Last Hurrah, Ford’s peek behind the scenes at local politics, and not necessarily the last word from myself either. What I’m talking about here is the western and in particular that brief period of time when it was still recognizably classical in form and feel, and not long before the changes which saw it rapidly evolve away from its roots towards something quite different would begin to become more apparent. So, the beginning of the end, or the end of the beginning? The answer to that will of depend on how one regards the direction and impact of those changes.

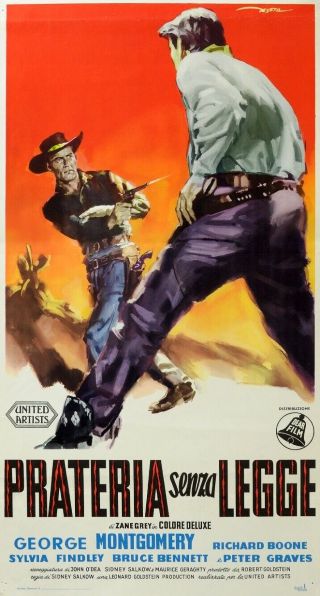

I have settled on taking a look at two movies from the same year, the date carries some significance in itself, which have at least one element in common. They also happen to be movies that I found myself watching as a result of recent revisits to a couple of others. The year in question is 1961, right on the cusp of the transition to the next stage of western filmmaking. That is not to say these films represent the end of the classical era of the western; that tends to be broadly accepted as coming about a year or so later, but they are poised (or teetering, if one feels less charitable about the subsequent years) on the edge of a major shift. The titles are Posse from Hell and The Comancheros and the most obvious link between the movies can be found in the writing: Clair Huffaker wrote both the original novel and then the screenplay for the former and produced the initial screenplay for the latter, before James Edward Grant finished it off. These films have something of the Janus aspect to them, casting wistful glances at the glories of the preceding years and simultaneously squinting ahead into the glare of a less certain future, even the characters within seem unsure in which direction they ought to be gazing.

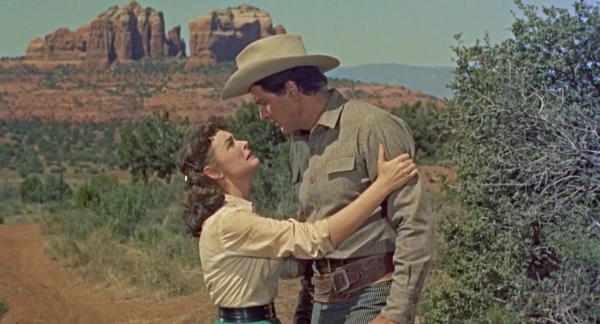

Posse from Hell is one of Audie Murphy’s better westerns from the 1960s, none of which are actually poor, and taps into the implacability that formed the core of the man. His reluctant deputy has a steely independence about him, a coldness he was able to slip into when required and which is always credible. His dogged pursuit of Vic Morrow’s gang of four fugitive killers reminded me of the similarly relentless way Gregory Peck went about tracking down four men (incidentally, one of whom was played Lee Van Cleef in both cases) in Henry King’s magisterial The Bravados. Perhaps the fact I’d seen that movie again not long before had planted the seed in my mind, but the driven determination they both feature struck me. And yet the contrast was apparent too; King’s film had a more personal vibe, and the solid moral point it successfully hammers home is more powerful. In Posse from Hell even the motives of Morrow and his companions is abstruse, they seem to do bad things simply because they can and with no particular goal in sight. That is not to say the script has no ethical aim, Murphy’s rejection of the puritanical judgements of others and the final realization by him and Zohra Lampert that intolerance isn’t necessarily universal refute that charge. Nevertheless, it all plays out like a less anchored and more sensationalized version of tales told before.

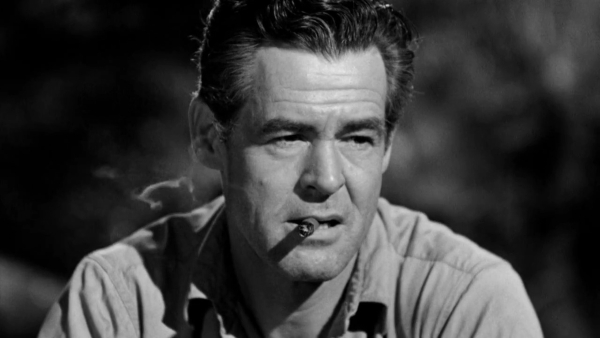

The Comancheros, quite literally the last hurrah for Michael Curtiz to the extent he was so ill that some of the director’s duties fell to John Wayne, while enjoyable enough was already starting to feel slightly dated. There’s an unevenness to its tone that jars occasionally and dilutes what is at heart a harsh story. The whole concept of arming people to allow them to carry out atrocities has a certain unpleasantness about it, and the process of hunting down those who indulge in this sits uneasily next to some of the knockabout comedy on show. Even having Wayne’s undercover Texas Ranger take part in one of those cartoonish brawls with Lee Marvin feels odd given the nature of the latter’s half-scalped renegade character. There are also scenes of the aftermath of a Comanche raid, replete with corpses strung up and these are juxtaposed with more semi-comedic actions by Stuart Whitman wielding a shovel. Similar criticisms can be leveled during the climax at the Comanchero hideout, with hideous punishments sitting side by side with scenes of comically drunken Indians. As such, the script feels indecisive, unable to make up its mind as to what kind of movie it wants to be. This is very likely down to the way it was started by Huffaker and then rewritten by Grant.

Another viewing of Rio Conchos, which adapts a Huffaker novel and tells a somewhat similar story, served to highlight these inconsistencies. That film of just a few years later maintains a much tougher and harder-hitting focus. Of course, by that stage, the redemptive nature of westerns was being increasingly challenged – not entirely wiped out but certainly infected with a strong dash of cynicism and hints of the full-blown nihilism that the influence of the Spaghetti western would allow to drift in. Looking at these films and the involvement of Huffaker in their production has me wondering whether, if one is prepared to accept them as part of the transitional process, the author himself here should be thought of as part of the transition that was underway in the the genre. Answers on a postcard…

So there you have it, two quite different movies in theme and style yet both produced in the same year and from the same pen. That in itself makes them interesting to me, and then when you factor in how reflections of the past can be discerned alongside harbingers of the future it adds some further food for thought. The process of change is a fascinating one, it is after all the connecting fabric of life, and while the way it can be traced in westerns may not always be satisfying it is something which draws me back time and again.

Initially, I had intended to take a look at three movies here, including one more from the following year with the aim of examining the development underway and, hopefully, making some point about where things were heading in the genre. However, I found it was all growing far too long and the risk of boring readers led me to break it up into two separate posts. The other movie therefore gets its own entry, perhaps deservedly so, and will be posted in due course. As such, while this post can be read as a stand alone it can also be taken as the first of a two part look at a pivotal moment in the western genre.