“From the start, it all went one way. It was in the cards, or it was fate or a jinx, or whatever you want to call it.”

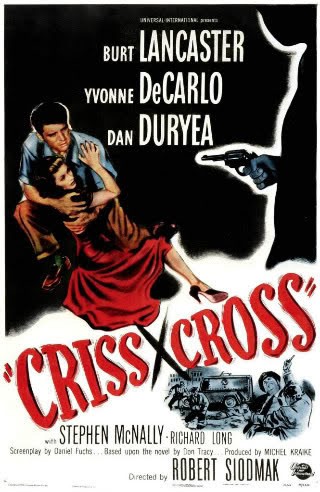

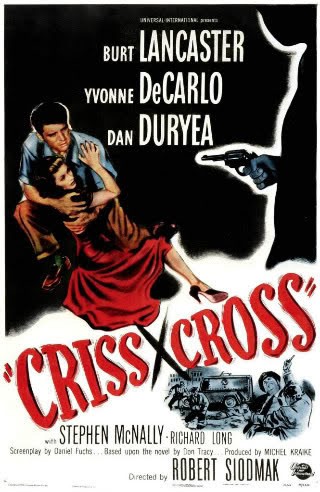

Burt Lancaster, Robert Siodmak, a heist, a hero doomed by fate and his own stupidity, and a rotten to the core femme fatale – all of this sounds a little like a brief synopsis of The Killers. In fact, it refers to Criss Cross (1949), a near relative of that earlier work and a film that vies with it for the honor of being hailed Siodmak’s best movie. Apart from the pairing of director and star, both these films share a similar theme and structure, and I find it almost impossible to decide which is the better one. Ultimately, it doesn’t matter – I like them both and they are two of the strongest noir pictures to come out of the 1940s.

The title of this movie is a highly appropriate one for a tale where the paths of all the main characters are continually intersecting in a web of deceit and betrayal, each crossing up the other at the first opportunity. At the centre of it all are three people – Steve Thompson (Burt Lancaster), Anna (Yvonne De Carlo) and Slim Dundee (Dan Duryea) – bound together by an unholy combination of love, lust and greed. The opening shot, with the camera swooping ominously down from the night skies of LA, sees Anna and Steve caught in a clinch in the parking lot of a nightclub. As the lights suddenly pick them out, their startled and guilty reaction indicates that this is an illicit rendezvous. The fact is further underlined by the terse, tense dialogue – this couple is planning something dangerous, and the possibility of discovery holds a terrifying threat for them. Anna is married to local hood Slim Dundee, but she and Steve were once wed too. Their passionate embrace makes it clear that they have rekindled their old relationship, with the flame burning brightest for Steve in particular. And it’s from the point of view of Steve that the story is primarily seen, with the others moving in and out of the picture at various intervals. He’s a classic noir protagonist, a fairly ordinary guy with limited prospects and a blind spot where no-good females are concerned. A lengthy flashback sequence, accompanied by a suitably weary and resigned voiceover by Steve, spells out exactly how the lives of these three characters converged and the complex ties that continue to bind them together. In short, Steve’s job as a guard for an armored car company has led to his conspiring with Dundee to raid one of the secure vehicles. However, in the noir universe there’s no such thing as honor among thieves and everyone has his own hidden agenda. Steve is the only one of the trio whose motives have some semblance of decency – he’s driven by a kind of desperate love for Anna – and the aftermath of the heist shows just how deep the fault lines of treachery run in this uneasy alliance.

Apparently the untimely death of Mark Hellinger meant that the original script was revised and certain aspects of the story were changed. Be that as it may, the movie that we ended up with is almost impossible to fault and Daniel Fuchs’ script successfully blends the heist and Steve’s obsessive love to powerful effect. Flashback structures can sometimes be confusing or upset the mood of a film but in this case it works perfectly, coming at precisely the right point and filling in the background details that are vital to understanding the nature of Steve and Anna’s relationship. With a tight script, and Franz Planer’s photographic talents, in place, director Robert Siodmak was free to put it all together with his customary visual flair. The opening, which I referred to earlier, pitches the viewer headlong into this complex tale of dishonor and betrayal in incredibly stylish fashion. And it never really lets up from that moment, with one memorable and superbly shot scene following hard on the heels of another. Siodmak uses every trick up his sleeve to manipulate the mood and perspective, from coldly objective overheads to disconcerting low angles and close-ups, interspersed with fast cuts and dissolves. For me, the real stand out scenes, although there’s hardly a poor moment throughout, are the ones in Union Station and in the hospital. The former not only gives a fascinating glimpse of contemporary LA bustle, but also shows the director’s skill in composing a complex series of shots in a crowded environment while retaining control of the geography. In the latter, he uses the reflection from the mirror in Steve’s room to break up the static nature of the setup and extract the maximum amount of tension at the same time.

If the technical aspects of the film are straight out of the top drawer, then the same can also be said for the acting. Burt Lancaster kicked off his career with some finely judged playing as the doomed Swede in The Killers, and Siodmak got him to tap into that same vibe to coax another wonderfully nuanced and sensitive performance from him. Once again he hits all the right notes as the big palooka whose dark romanticism sees him suckered by the machinations of a conniving woman. Every emotional state the script calls on him to display is carried off convincingly, from fear and disenchantment right through to the calm acceptance of his fate at the end – from the dumbfounded look of a guy who’s just had his guts kicked out by the woman he loves to the cloying sense of panic of a man under sentence of death and trapped in an anonymous hospital ward.

Yvonne De Carlo didn’t have to go through quite as many stages, yet she’s still excellent alternating between the sassy, sensual broad that forms her public persona and the nervy, desperate woman she becomes in private. When she drops all pretense in the climax and reveals her true character to Steve and the audience there’s a tangible shock to be felt. Dan Duryea was an old hand at taking on the role of the slimy villain, and to that he adds a layer of menace as Slim Dundee. He manages this so well that it’s easy to understand the level of fear and trepidation he provokes in Steve when he contemplates the consequences of crossing him. While these three actors carry the movie, there’s real depth in the supporting cast too. Stephen McNally is solid and sympathetic as the cop whose friendship for Steve leads him to inadvertently push him into crime. In fact, there are lovely little cameos all through the movie: Percy Helton’s chipmunk featured barman, Joan Miller’s garrulous barfly, Griff Barnett’s kindly and lonely father figure.

Criss Cross has been out on DVD for many years now, and the US disc from Universal is an especially strong effort. It offers a near perfect transfer of the film with clarity, sharpness and contrast all at the high end of the scale. My only disappointment comes from the absence of any extra features, bar the theatrical trailer, for such a quality movie. One shouldn’t really complain, in these days of bare bones burn on demand discs, but this film does deserve a commentary track at the very least. Still, we have got an excellent piece of the filmmaker’s art looking great. Criss Cross is a highly rated production that occupies a prominent position in the noir canon, and it has earned that honour. It’s one of those rare films that checks all the boxes and never puts a foot wrong from its dramatic opening until it’s darkly cynical final fade out. Those who are familiar with the picture will know exactly what I’m talking about, and those who are not owe it to themselves to discover this little treasure. This is unquestionably one of the real jewels of film noir.