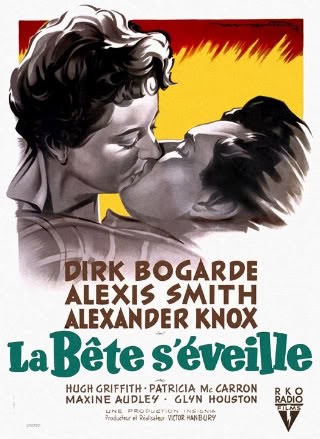

Would you consider taking a known criminal into your home as an experiment? That’s the basic premise of The Sleeping Tiger (1954), and it’s one that promises ample opportunity for drama and tension. Unfortunately, the unlikely nature of such a story leaves the material ripe for a descent into some highly strung melodramatics. Of course this is a movie, and what matters most is internal logic – the situation in which the characters find themselves doesn’t necessarily have to be one the viewers would choose for themselves so long as those characters behave appropriately within the given framework. In this movie, that is pretty much the case yet the result remains only partially successful.

Frank Clemmons (Dirk Bogarde) is a young hood with a troubled past. When he attempts a late night hold up on a deserted street he finds himself abruptly overpowered, disarmed and, to all intents and purposes, a prisoner. The intended victim was Clive Esmond (Alexander Knox), a psychiatrist with a penchant for experimentation. Instead of handing his would-be mugger over to the authorities, Esmond wants to see if he can put his theories into practice and rehabilitate the young delinquent. To this end he makes a deal with Clemmons: he will stay in Esmond’s suburban home, ostensibly as a guest, while the doctor attempts to dig into the past and exorcise the demons. So far so good, and maybe very laudable too. But there’s inevitably a fly in the ointment – the woman. Glenda (Alexis Smith) is Esmond’s young American wife, leading a life of leisure but starting to feel just a little bored. Though initially hostile to Clemmons, it’s only a matter of time before she allows herself to be seduced by his dangerous charm. While Esmond is becoming an unwitting cuckold, he is also gradually making progress with getting to the heart of Clemmons’ problems. A rash hold up by Clemmons, and an equally rash show of solidarity on Esmond’s part, leads to the breakthrough. Clemmons is free of the chains of guilt and Esmond has achieved a major professional success. But this is only part of the story, and the adulterous triangle that has sprung up will have to be resolved in a dramatic and violent fashion.

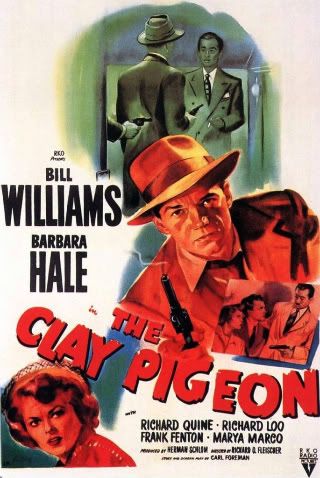

The Sleeping Tiger was Joseph Losey’s first British film after fleeing Hollywood and the HUAC controversy. He directed the film under a pseudonym (as did writers Carl Foreman and Harold Buchman) for fear his notoriety should rub off on any others in the cast and crew. His direction is competent without being in any way flash, and the film seems to be trying very hard to be a true noir. Indeed, there are many noirish elements, but the setting and characters are an obstacle. The whole thing remains resolutely British in a way that, while not damaging in itself, just isn’t noir. Dirk Bogarde gives a good enough performance as Clemmons but, and this is a big but, he simply doesn’t convince as a hardened hoodlum. His part was so written to allow him to come from a middle-class background and help account for his sophistication. Still, it doesn’t really work and, despite his ability to play villains and cads, Bogarde is never credible as a gun-wielding street thug. In the role of Esmond, Alexander Knox is fine and draws a good deal of sympathy. The only real issue I had was the fact that there’s no explanation offered as to why this man would so obsessively (and he does go to extraordinary lengths) endanger himself and his household for the sake of curing one patient. Alexis Smith was at the end of her big screen career at this point (she was moving into television work) but she turns in an excellent performance as the neglected wife who’s the real sleeping tiger. She gets to indulge in some scenery chewing melodramatics towards the end, and does so very effectively.

As far as I know, The Sleeping Tiger is only available in poor PD editions in the US. However, there are a couple of ways to get hold of it in the UK. Optimum have released the film in two box sets, one dedicated to Joseph Losey and one to Dirk Bogarde. I watched it from the Bogarde Screen Icons set, and the transfer is fine, clear and sharp with only a few minor scratches on view. The disc itself is a totally barebones affair and no subs are provided. The film offers an interesting if unlikely mix – The Dark Past being another variation on this theme – of psychoanalysis and crime that has its moments. The melodrama is laid on a little thick at times and the casting of Bogarde is somewhat problematic. Despite this, it remains watchable and marks the first collaboration of Losey and Bogarde, who would go on to make more accomplished films together.