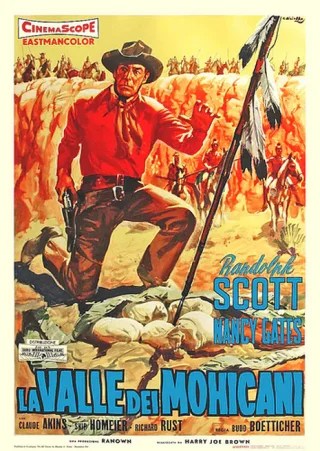

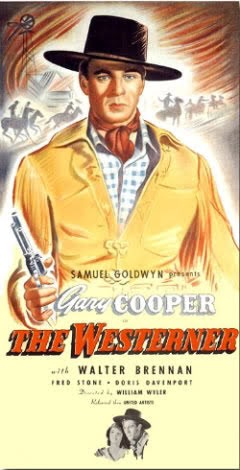

One of the recurring themes of the western is the conflict between the cattlemen of the open range and the fence-building homesteaders, or sodbusters. In truth, this clash (freedom, as represented by the range, and the slow encroachment of civil society from the east) lies near the very heart of the genre. It is this which forms the framework of The Westerner (1940), but the film really revolves around the relationship between two very different men. As such it eschews action in favour of character development, and slots nicely into the group of more mature westerns that were starting to appear at the time.

The film’s prologue sets the scene in the years following the Civil War when the westward expansion was in full swing. Judge Roy Bean (Walter Brennan) has established himself as the self-styled “Law West of the Pecos” in his own remote corner of Texas. He is shown dispensing his own brand of justice from his saloon/courtroom in the case of a man accused of committing one of the most serious of all crimes, that of murdering a steer. Having tried, convicted and carried out the sentence personally, he comes face to face with his next defendant. Cole Harden (Gary Cooper) is a drifter and saddle tramp who’s had the misfortune of buying a stolen horse. This is another capital crime and the case looks to be an open and shut one. When the jury retires to back room to play cards and down some liquor before delivering the inevitable guilty verdict, Harden takes the only path open to him. Noticing that the saloon has been made up as a virtual shrine to Lily Langtry, Harden claims to have made the acquaintance of the judge’s beloved actress and to have a lock of her hair in his possession. Well, clearly such a man can’t simply be hauled out and hanged so the sentence is suspended and the two men form an uneasy alliance. However, Harden finds himself drawn to Jane Ellen Matthews (Doris Davenport), daughter of a local settler, and is soon caught between the two rival factions.

Gary Cooper was a highly deceptive actor. There are those who would claim that his laconic style was wooden and that he couldn’t act, but to say that is to ignore the subtlety of the man’s craft. There was no expansiveness to Cooper but everything was communicated through his face and small unpretentious gestures. There is a marvellous example of this during the trial scene in this movie where fear, calculation and, ultimately, triumph are all readable just from his eyes. He’s at his best in the scenes he shares with Walter Brennan but, perversely, has every one of those scenes stolen right from under his nose. I don’t think it would be too much of a stretch to say that Brennan was the finest character actor American cinema has ever produced. He turned in performances which ranged from fine to excellent in anything I’ve seen him in. His Judge Roy Bean is a multi-layered character who goes from mean and ornery to endearingly childlike and back again. It’s no mean acting feat to make this figure sympathetic, but Brennan managed it and picked up his third Oscar for his troubles.

Visually, the film looks great, due in no small part to the photography of Gregg Toland. With all this talent at his disposal, director William Wyler marshals it with his typical professionalism. He offers up some fine cinematic moments, such as the attack on the homesteaders. In the midst of a thanksgiving ceremony, as the camera surveys a rich, tranquil and fertile land to the accompaniment of noble words, the idyll is abruptly shattered by a murderous arson raid. As flames sear the screen, the settlers paradise is transformed in a matter of minutes into a scorched, desolate landscape. Those smouldering, blackened ruins of former homes pointing accusingly towards the heavens are an eloquent reminder of the fickle and dangerous unpredictability of frontier life.

The Westerner was reissued on DVD in R1 late last spring by MGM/Fox and the transfer is a very fine one. I can’t say I noticed any significant damage marks or signs of manipulation, just a crisp, clean B&W image. Previous MGM releases were no more than adequate but the distribution deal with Fox seems to have led to an improvement in quality. The only criticism is the lack of any extra content, but I guess you can’t have everything. I’d rate The Westerner as a good example of a ’40s oater for grown-ups; it has drama and it’s moving but it also has a vein of sly, dark humour running through it. Recommended.