“Some people say it didn’t happen that way…..”

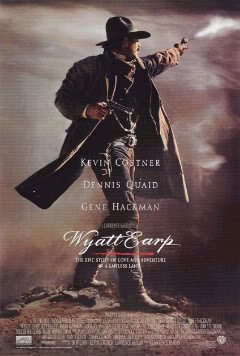

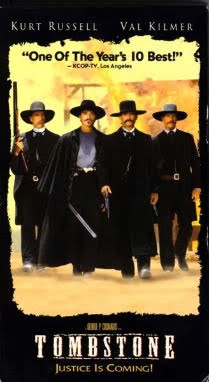

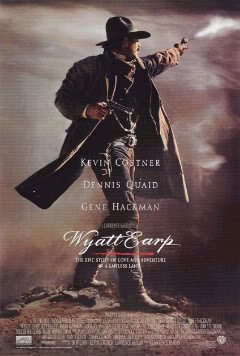

I want to preface this piece by saying that Wyatt Earp is a film for which I’ve never had any particular fondness. However, having said that, I’ve just watched it again after making a conscious decision to try and keep an open mind, and hopefully be as objective as possible. I first saw the film during its initial theatrical run and then later on DVD. I can’t honestly say that I was relishing the prospect of another viewing but I didn’t feel I could round out my series without revisiting this movie. For most film fans any discussion of Wyatt Earp almost always leads to its being compared to Tombstone. Given that both films featured the same lead characters and came out so close together, such comparisons are inevitable but not necessarily fair. While Tombstone focuses on one particular time and place, Wyatt Earp is a sprawling epic that attempts to cover the course of the man’s life. I used to wonder if the fact that I saw Tombstone first colored my opinion in any way, but I don’t now believe that’s the case. I thought Wyatt Earp was a flawed picture on my initial viewing and I still feel the same.

The story begins during the Civil War when Wyatt was helping look after the family farm in Iowa while his older brothers James (David Andrews) and Virgil (Michael Madsen) were off fighting. He is shown attempting to run away to enlist only to be caught and brought back by his father (Gene Hackman). This event, and the subsequent return from war of the brothers, is the cue for some heavy-handed speech making from Hackman. The point of this is to show how Wyatt’s views and attitudes were formed from an early age but I’ve never been keen on this technique for showing character development, it’s always struck me as a lazy way of making a movie. Anyway, having bludgeoned home the point that blood ties are the major motivating force in the young man’s life, the film follows the family on their long trek west to the promised land of California. From there we get snippets of Wyatt’s time as a teamster and how he gained experience in facing down bad men. A fair amount of time is spent on his move to Missouri in order to marry his childhood sweetheart, who succumbs to typhoid soon after the marriage. I found this part of the film dragged a lot although the purpose of its inclusion is to provide an explanation for Wyatt’s later emotional detachment. The pace does pick up when Earp moves to Wichita, Dodge, and ultimately Tombstone, all the while building and expanding his reputation as a fearsome lawman. This is certainly the strongest section of the film and it has to be said that the producers went to great lengths to recreate the look and feel of those wide open frontier towns. It’s also the part of the film that introduces some major characters Doc Holliday (Dennis Quaid), his woman Big Nose Kate (Isabella Rossellini), and Bat and Ed Masterson (Tom Sizemore & Bill Pullman).

Everything builds towards the fateful confrontation with the Cowboys in Tombstone and its aftermath. The O.K. Corral scene is filmed well enough but it just doesn’t carry the punch that such a defining event should; after all, had this not taken place no one would ever have thought to make films about these characters. The resulting vendetta is nowhere near as exciting as it should be and never conveys the sense of the righteous settling of scores that one expects. One major gripe that I had was in the scene showing the climactic gunfight at Iron Springs. Before this the character of Johnny Ringo had barely been mentioned, let alone portrayed. Yet here we have the Earp posse riding into a hail of gunfire, and Doc shouts out the name of Ringo before blasting a faceless man high up in the rocks. If the writers hadn’t wanted to use this character, that’s fair enough – just ignore him. But the way it was handled made me feel that they were sitting around and suddenly realised that here was another name they had to check off the list before things could be wrapped up. In a sense this sums up a serious weakness in the movie, namely the portrayal of the villains. If you’re going to make a big film then you need to ensure that the bad guys are big and bad too. In Wyatt Earp the Cowboys are poorly defined and never provide any real feeling of threat, they’re just a bunch of grubby, unshaven guys who look vaguely mean. Of course I’m aware that this may be closer to the truth but the point is that such realism does not make for a good film. Let’s just say it’s never good news when one of your principal baddies is played by Jeff (straight-to-video) Fahey.

So, for me, the greatest flaws in the movie are the acting and the scale. Costner’s acting style may well be an acquired taste, if so I have yet to acquire it. I could be generous and say that his is a restrained performance but the truth is that he simply comes across as wooden. Every line, no matter what emotion lies behind it, is delivered in the same careful, measured tone. Even if this is true to the character it makes it impossible for the viewer to connect in any way. Dennis Quaid’s Doc Holliday definitely comes off the best but, again, it’s hardly an endearing performance. The real man may not have been a charming figure, but Quaid gives us an irritable and irritating jerk that even Wyatt Earp would have had a hard time considering a friend. There’s also something forced about his interpretation; he certainly looked the picture of bad health but I always had the sense that I was watching an actor in a role, not a real person. The support cast are largely disappointing but the best of the bunch is probably Bill Pullman as the ‘affable’ Ed Masterson. Michael Madsen’s Virgil Earp is generally colorless, but then I’ve always thought that Madsen is a rather limited actor who’s nowhere near as tough as he’d like to think. In general, the cast is filled up with too many nobodies and TV actors, which means too many flat and lifeless performances.

As I said, the scale of the film is another problem – and one that seems to dog many of Costner’s projects. In brief, it’s too long and tries to pack in too much. By attempting to chart the life of this man the film has both too much detail and too little. This results in characters coming and going without the audience getting the chance to know them in any way. Having said that, it does look good and there are some beautifully composed shots of the western landscape. Also, James Newton Howard’s score has that soaring, epic feel to it. Ultimately, though, the film disappointed me and left me feeling as cold as the Alaskan landscape in the final shot.

Wyatt Earp is on DVD from Warner in R1 and R2 in its theatrical cut. As far as I know, the extended cut has never been available on DVD – in a sense I’m grateful for that since I’m of the opinion that a few more trims wouldn’t have hurt this one. I know some may see this as a bit of a hatchet job, but I have tried to give my own honest assessment of the movie and what I feel are its flaws. I hope my efforts at articulating my views make some sort of sense.

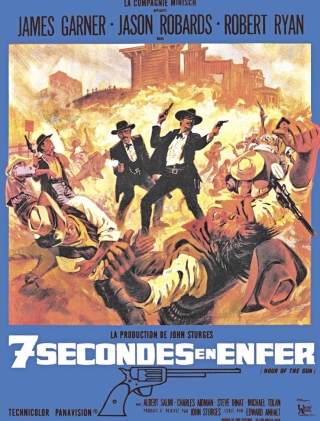

So, one month and eight films later, I have come to the end of my series of reviews of the Wyatt Earp movies. I have to say it has been enjoyable for me to go through them all back to back, and I can only hope the readers of this blog haven’t been bored witless by it. What I have noticed most in this lengthy perusal, apart from the increasing focus on realism, is how the character of Wyatt Earp evolved – from the generic and uncomplicated western hero of Randolph Scott, to the taciturn and unsympathetic professional of Kevin Costner. Each characterization added a little more depth to the legend and simultaneously stripped away a little of the myth to reveal more of the darkness inside. I still feel that, despite all the inaccuracies, My Darling Clementine is the best of all the films. I would rank Tombstone as the most entertaining and arguably the most accessible. Unfortunately, I would have to place Wyatt Earp far down the list, maybe even at the bottom – it was just too ambitious and ultimately unable to deliver all that it promised.