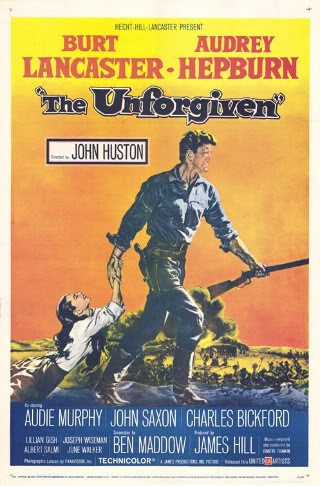

John Huston has to be one of my favourite directors but I’ve only just realised that, before today, I hadn’t written up any of his films on this blog. A quick browse through his lengthy and wide ranging filmography also drew my attention to the fact that he only made two westerns – I’m not counting The Misfits or The Treasure of the Sierra Madre, although some probably would – and I thought that seemed a little odd. The Unforgiven (1960) is a movie that doesn’t get talked up very much (the director professed a dislike of it which may have hurt its reputation some) but I believe it’s worthy of a bit of attention. The movie derives from a story by Alan Le May (The Searchers) and, perhaps unsurprisingly, concerns the fate of captives. What makes The Unforgiven a little different is the fact that the abduction that forms the background is a reversal of the usual white child spirited away by Indians one. In this case the settlers have taken a Kiowa baby and adopted her as one of their own. This storyline offers the opportunity to examine the effects of racism not only within the community but within the confines of the family as well.

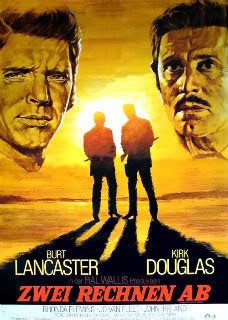

The Zachary’s are a close knit frontier family who, with the father dead as a result of a Kiowa raid, are held together by eldest son Ben (Burt Lancaster). He, with the help of brothers Cash (Audie Murphy) and Andy (Doug McClure), has been putting together a herd of cattle to send to Wichita and make their fortune. The family’s future looks secure and there is a chance of marrying the only sister, Rachel (Audrey Hepburn), into a neighbouring family of fellow ranchers, thereby cementing their partnership. However, the Zacharys’ dreams are built on shaky foundations and are soon to be swept away. Into their midst rides a mysterious old man (Joseph Wiseman), clad in a decaying Civil War uniform complete with sabre. In between quoting scripture he tosses out casual innuendo relating to a dark secret held by the Zacharys. Before long, Ben and Cash find themselves having to hunt down this otherworldly figure, knowing as they do that he intends to destroy them. This leads to one of the most memorable scenes in the film, as the two brothers chase their ghostlike quarry through a swirling dust storm – the old man seeming to appear and disappear at will, and then rushing out of the clouds of windswept sand with his sabre swinging murderously. Nevertheless, despite their best efforts, their nemesis evades them and poisons their neighbours and former friends against them. By the time the Kiowa turn up outside the sod covered family home demanding the return of what they claim belongs to them the Zacharys are about to tear themselves apart. Cash is an unashamed racist haunted by visions of his father’s death at the hands of the Kiowa, and barely able to contain his contempt and hatred for the red men. Therefore, Ben must prove himself the rock upon which the others can depend in order to weather the gathering storm.

I’ve read that John Huston may have been displeased with the final product due to the fact that Audrey Hepburn later suffered a miscarriage, possibly as a result of a fall during production, not to mention that Audie Murphy almost drowned etc. Be that as it may, the film remains a solid, professional piece of work from Huston. He and DOP Franz Planer made excellent use of the wide angle lens to capture the scenery around Durango, and it contrasts well with the dark and claustrophobic interiors of the Zachary home. Apart from the aforementioned dust storm, the action scenes during the climactic siege are quite impressive.

The cast as a whole acquit themselves very well, with Lancaster displaying his customary stoicism interspersed with the occasional witticism. Audrey Hepburn would hardly rank as anyone’s idea of a western heroine but I thought she was pretty convincing in a difficult role. Audie Murphy never gets a lot of credit as an actor but this movie, probably more than any other, shows just how capable he was. He invests the character of Cash with a simmering mix of conflicting emotions that enables him to steal almost every scene he’s in. Lillian Gish also has a high old time as the tough matriarch with a steely resolve, and has a wonderful scene where she sits playing the piano outside at night to counter the music of the Kiowa medicine men. Joseph Wiseman chews up everything in sight as the spectral (no pun intended) Abe Kelsey, a genuinely scary yet pitiful husk of a man driven insane by grief and a desire for vengeance on those he deems responsible for past wrongs.

Given the indifferent treatment MGM often handed their catalogue releases the R2 DVD of The Unforgiven is actually quite pleasing. It’s given a handsome anamorphic scope transfer that has little damage on show save for a bit of light speckling here and there. Since this film is not widely regarded as one of Huston’s greatest it’s no real surprise that the only extra available is the theatrical trailer. I think this movie has been unjustly maligned by many and, even if it never comes to be seen as vintage Huston, it does work well as a mature western that at least tries to tackle a complicated issue. All in all, I like it and feel the performances and photography are ample reasons to give it a go.