“…the right of the public to a marketplace of ideas, news and opinions. Not of one man’s, or one leader’s, or even one government’s.”

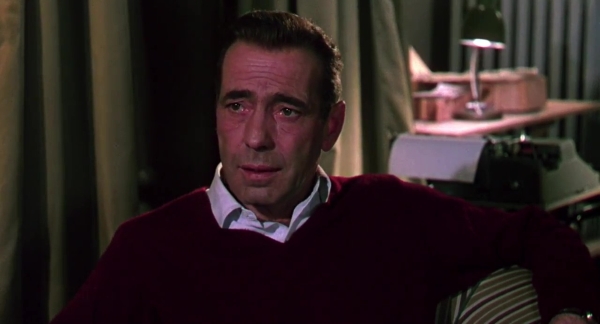

That eulogy to the Fourth Estate, not merely to its desirability but to its necessity as a vital pillar of a functioning democracy is delivered relatively late on in Deadline – U.S.A. (1952) by Humphrey Bogart’s committed and conscientious editor. It might come late in the movie yet everything has been building towards that and the narrative would already have led us to that conclusion even if the script had not spelled it out. If this point needed to be made back in 1952, it is arguably even more essential now where the current era of demagoguery sees the foundations of democracy chipped away at on a daily basis.

On various occasions throughout the film various characters refer to a murder, a wake and a funeral. It’s as though the shadow of death hangs heavily over the entire project. However, it’s not the death of person, even though there are a handful of those folded into the plot, but instead the demise of a newspaper which is alluded to. This sense of a paper as a living entity, with as much conscience and soul as a human being, pervades the movie. To be perfectly frank, the newspaper in question could be said to have more human characteristics than some of the individuals portrayed. Anyway, this anthropomorphism is key to understanding Deadline – U.S.A. and the points writer and director Richard Brooks seeks to hammer home. The paper in question is The Day, a publication which prides itself on its standards and its history. The editor Ed Hutcheson (Humphrey Bogart), as well as the staff, regards it as a newspaper as opposed to a purveyor of sensationalist yellow journalism. Despite that noble intent, or a cynic might posit because of it, The Day is on its way out. Life support is about to be unplugged and the owners, the detached and disinterested heirs of the founder, are in the process of selling off the carcass to a competitor whose primary interest is buying it in order to close it down and thus corner the market. The viewer is invited to follow the final days of this venerable institution where regardless of the sense of inevitability, there is also a resilience on show. Maybe it’s a losing battle but Hutcheson isn’t going down without a fight and the battlefield he’s chosen for the paper to stage its last stand is one reigned over by Tomas Rienzi (Martin Gabel).

Rienzi is an old school hood, one of those guys where the patina of civilization is especially thin. He’s been investigated for corruption and graft but nothing seems to stick. This time may be different though – the body of a mink clad good-time girl has been fished out of the river and gradually a trail leading back to this Teflon don becomes apparent. In essence, a race takes place to see whether all the connections can be made before the courts put the seal on the sale of the paper, or before Rienzi’s enforcers can make enough witnesses and whistleblowers disappear. While there are other subplots touched on to varying degrees, it is here that the movie sets out its stall. Brooks wants to make the point that real journalism serves a vital civic purpose – “to comfort the afflicted and afflict the comfortable” if you like. Personally, I think his argument is both valid and worthwhile, maybe even more pronounced now than it was all those decades ago. If the printed press has gone into near terminal decline, the voice, function and long established ethics of the legacy media remain essential, even as they come under attack from a range of chiselers and charlatans.

Movies about journalism, indeed the same could be said for that other subset movies about the movies themselves, seem to have their own special energy. That such productions should exhibit a vitality ought not to be much a surprise when one stops to think how many writers and filmmakers had a background in journalism. The accepted wisdom is to write about what you know and there’s plenty of evidence to suggest that this kind authenticity does lend an added touch of passion to proceedings. Richard Brooks was one of those writer/directors who started out working as a reporter and the latent respect for the trade colors what he puts up on the screen in Deadline – U.S.A. – that said, I do seem to recall seeing an interview he gave many years later where he expressed dissatisfaction with the title, feeling that it was meaningless in itself. Well if the title is somewhat awkward, the arguments underpinning the plot are not. Brooks keeps it moving along, capturing the noise and urgency of both the newsroom and the press room. There are a couple of instances of less convincing back projection but Milton Krasner has it looking attractive for the most part. Outside of the newspaper building itself, the most effective scene is that inside Rienzi’s car, where he and Hutcheson spar and both Bogart and Gabel make the most of Brooks’ snappy dialogue.

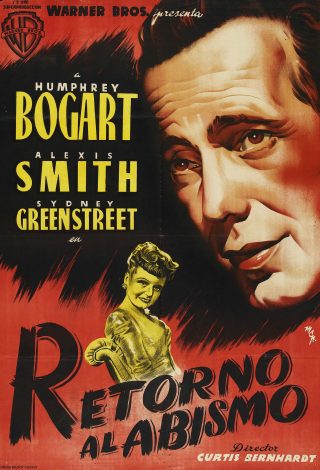

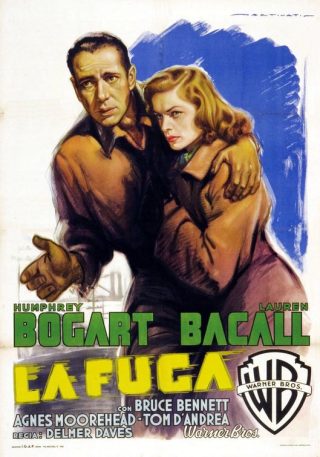

By this stage Bogart was an old hand at either playing it tough and cynical or tough and noble. He goes down the latter path here and his conviction is never in doubt whether he’s trading threats with a mobster or arguing ethics in the boardroom. The only less convincing aspect is his attempt to rebuild his marriage with his ex-wife Kim Hunter. She was an accomplished actress with successful work in A Streetcar Named Desire and A Matter of Life and Death behind her yet there’s a certain listlessness to her performance in this film which weakens that plot strand. On the other hand, Martin Gabel is a fine adversary for Bogart, desperate to convey respectability – “I’m in the cement and contractin’ bu’iness” – while his rough edges keep poking through the facade. There’s plenty of menace on display from Gabel, a man I’ll always associate with the role of Strutt in Hitchcock’s Marnie, but who also directed the atmospheric The Lost Moment.

As is frequently the case with big studio productions of the era, there is strong support from a deep cast of familiar faces. Ethel Barrymore rolls out her wise old owl act once more, but she does it so well and so attractively that it’s a pleasure to watch. Ed Begley is comfortably solid, and Paul Stewart (someone else who could shift with ease between villainous and sympathetic parts) casts alternately weary and wary looks from beneath his ever expressive brows. Joseph De Santis has a ball as the scumbag brother of the murder victim, smirking and sweaty as he chisels his way to an undeserved payday before making a spectacular exit where he literally becomes front page news. Jim Backus, Tom Powers, Warren Stevens, Fay Baker, Joe Sawyer and Willis Bouchey among others drift in and out. Apparently, James Dean had a small uncredited part but I’ve never been able to spot him even after numerous viewings.

I’m not sure how well regarded Deadline – U.S.A. is or what kind of reputation it has. I do know I’ve always liked it, it has one of those roles which feel tailor-made for Bogart and the sentiments of the script appeal. I guess I’m something of a sucker for movies focused on newspapers and reporters. It should be easy enough to access in good quality these days; this was not always the case but there are high grade Blu-rays and DVDs of the movie available in most territories now – I have the German DVD myself. While the more venal sections of society endeavor to undermine public trust in the integrity of the mainstream media, it’s good to remind oneself of how important it was and is to all of us.

As an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases made through links on this page.