“You’re a dreaming idiot, and that’s the worst kind. You know what the trail is really like? Dust storms all day, cloudbursts all night. A man has got to be a fool to want that kind of life. And all that hogwash about horses! The loyalty of the horse! The intelligence of the horse! The intelligence? You know a horse has a brain just about the size of a walnut. They’re mean, they’re treacherous and they’re stupid. There isn’t a horse born that had enough sense to move away from a hot fire. No sensible man loves a horse. He tolerates the filthy animal only because riding is better than walking…. Pour me a little more whiskey there, will you?”

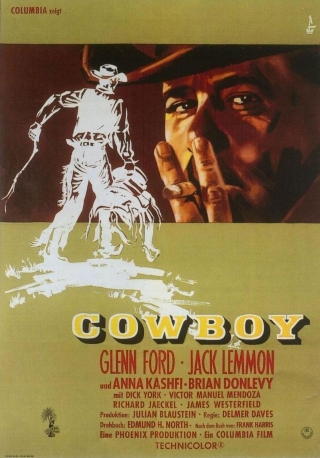

The myth, and how to deconstruct it. Those lines above, quoted by Glenn Ford’s world-weary trail boss as he lies in a hot bath he’s traveled the length of the country for, drinking whiskey from a china cup and shooting cockroaches off the wall, seem to rip the romantic facade away from the genre. We’re looking at a man who is bone tired, more than a little jaded and in no mood to indulge the highfalutin fantasies of Jack Lemmon’s lovesick hotel clerk. Delmer Daves’ Cowboy (1958) therefore creates the impression that the movie is going to dispense with legends and instead print some mean and ugly truths. In a way it does too, at least in the sense that the kind of codology Ford holds forth against gets short shrift, and for long stretches it looks as though the whole thing is building towards a grim revision of the genre. Nevertheless, the deeper myth, that which informs and elevates the western movie is, unsurprisingly, what Daves was searching for and what he skillfully reaffirms by the end.

The structure is classically circular, starting and ending in what what is nominally the same place, creating the impression of a tale turning back on itself but finishing up on a very different level as far as the development of the characters is concerned. The story is seen through the eyes of Frank Harris (Jack Lemmon), an ambitious young man first encountered working in a hotel in Chicago. This is not where he intends to spend the rest of his life though and the fact he has fallen for a young Mexican woman and incurred the displeasure of her father is one of the factor’s influencing his plans. When the expansive and free spending Tom Reese (Glenn Ford) and his rambunctious cowhands book into the establishment, this sets Harris thinking and a run of rotten luck at the card table for the trail boss provides an opportunity worth seizing. In short, Harris makes Reese a loan of his savings to get him out of trouble in return for a partnership on the upcoming cattle drive, one which will conveniently take him all the way to Mexico. What follows is a classic trail story, one beset by difficulties posed not only by the hardships of the terrain and the hazards of the Comanche, but also by those stemming from the personalities and idiosyncrasies of one’s traveling companions. This site often looks at westerns underpinned by the theme of redemption but here it’s not so much that aspect that grounds the film as those near relatives: growth and renewal.

Cowboy is based on an autobiographical work by Frank Harris called My Reminiscences as a Cowboy. Born on the west coast of Ireland in Galway, Harris went on to lead what might reasonably be termed a colorful life, traveling throughout the United States and Europe and earning fame or notoriety (depending as ever on one’s point of view) in the process. He certainly wouldn’t be the first writer who is alleged to have added some embellishment to his experiences so it is hard to say how accurate the source of what is presented on screen is. That notwithstanding, Cowboy, with its script by Edmund H North and and an uncredited and still blacklisted Dalton Trumbo, tells a rattling good yarn with plenty of incident, all of which is predicated on a solid core message.

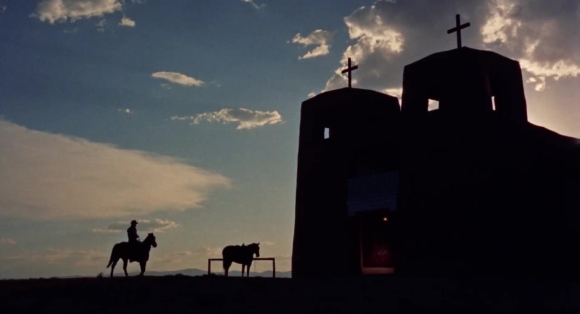

Every time I come back to a movie directed by Delmer Daves I’m once again struck by his focus on the better aspects of human nature. I see this as the defining characteristic of his work, that simple faith in humanity and its capacity for rising above the petty and the ignoble, and that perspective forms a large part of what draws me back to his films regularly. As was mentioned above, the redemption motif is not present in the movie as it doesn’t feature characters who have wandered down the kinds of paths that require a trip to that destination. What we do get are men who have either lost touch with or have yet to attain a fully rounded appreciation of humanity. So growth and renewal are the dominant themes, which I regard as a welcome detour. Daves was always very much at home shooting outdoors and he makes fine use of the Arizona and New Mexico locations, beautifully photographed by Charles Lawton Jr and with a fine George Duning score to complement the imagery.

For a long stretch it appears as though the plot is going to chart a hard bitten course, Harris soon has the exuberance knocked out of him by the unforgiving nature of both the environment and his companions. The whole purpose of his trek across the border is shattered in one moment of appalling revelation, a moment which threatens to tip him into a pit of despair and bitterness that is deep and steep sided. Similarly, Reese spends much of his time indulging his cynicism and abrasiveness. To all intents and purposes, that dismissive diatribe quoted at the head of this piece starts to sound more and more like a summation of the myth-busting stall the film has set out. Yet it’s a deceptive impression, for the characters played by Lemmon and Ford respectively learn and grow as a result of their experiences and their effect on each other. Lemmon had a knack for essaying a unique type of passion and enthusiasm that often felt manic and brittle. He comes perilously close to cracking under the strain and the provocations that come his way, but he matures in the process and tempers his excesses in a way that transforms them into strengths. Ford’s destination is slightly different, but just as fulfilling for the character and the viewer too. His path is essentially one of rediscovery and renewal, the bluster and machismo discarded as he witnesses the negativity of his influence mirrored in the meanness that threatens to harden the heart and damn the soul of his youthful partner. In support Brian Donlevy plays it quiet and pensive in a way that he didn’t always get the chance to, a disillusioned gunslinger looking for a different kind of life. There’s something very moving about his ultimate fate, and it proves to be one of the prime catalysts spurring Ford’s epiphany. Anna Kashfi (Marlon Brando’s first wife) is the only woman in a very masculine movie and although her role is important for its impact on Harris in particular, she’s only in the film for a short time. Richard Jaeckel, Dick York, Frank DeKova and Strother Martin are among those who also provide telling little sketches that serve to flesh out the story.

Cowboy is a fine Delmer Daves western, perhaps weakened somewhat by the lack of a more positive female character of the type that bolstered and added depth to his very best movies. Still, there’s much to admire in what we do get, visually, thematically and in the work of the principal cast members.

With this post I have now managed to cover all of the westerns directed by Delmer Daves. He’s a filmmaker whose work I never weary of sampling whatever the genre and his movies have been regularly featured here over the years. Below are links to all of his westerns that I have posted about.