Movies that exist at the periphery regularly catch my attention. They may be movies that occupy a place on the margins of a particular genre, they may be transitional efforts that straddle different eras, or they may even be a bit of both. Such is the case with River Lady (1948) a film which is not entirely successful, partly as it’s difficult to pin down the genre – a hint of the western, a dash of riverboat melodrama, and a pinch of the frontier adventure – and partly due to the time it was made. While it might not be the kind of movie that broke new ground or made a strong enough impression to encourage frequent revisits, it is still engaging in the way so many of George Sherman’s titles are.

I’ve lost count of how many westerns have turned a spotlight on the encroachment of civilization on the frontier. Sometimes it’s a matter of the railroad hammering out an iron clad tattoo across the plains and relentlessly shoving the old world to one side. At other times it is the stringing of the telegraph line, or the gradual extension of the reach of the law itself. River Lady concerns itself with the expansion of organized business interests, in particular the conflict between small, independent logging outfits and the hungry syndicates. Nevertheless, corporate kerfuffles of any type have a limited appeal at best and it’s always advisable to bring the human drama and the human faces of the players and antagonists to the fore. So it is that attention is focused on a roughneck logger called Dan Corrigan (Rod Cameron) and Sequin (Yvonne De Carlo), the owner of the titular paddle boat and undisclosed boss of the syndicate which is buying up all the struggling outfits on the river. This allows for a double-edged conflict, both the tangled business affairs and the romantic tug-of-war between a hardheaded free spirit such as Corrigan and the ambitious and manipulative Sequin. And any time the mixture looks like drifting off the boil the silky and stealthy Beauvais (Dan Duryea) is on hand to stoke it up once again.

As has been stated, in terms of genre, there’s a fluidity to the movie that mirrors the flow of the timber down the river. I guess that could be seen as versatility in the script, or even as a determination to resist the imposition of boundaries on the part of the filmmakers. However, it makes it hard to get a handle on the movie, a situation I’ve found can crop up from time to time in mid to late 1940s westerns, where it’s possible to detect elements of breezier B pictures rubbing shoulders with themes that carried a bit more weight. One could even say something similar about George Sherman’s career trajectory itself at this point. The rights to the story drifted around Universal for many years before the movie was finally made and perhaps this fairly lengthy gestation period has something to do with the feeling that the finished product imparts.

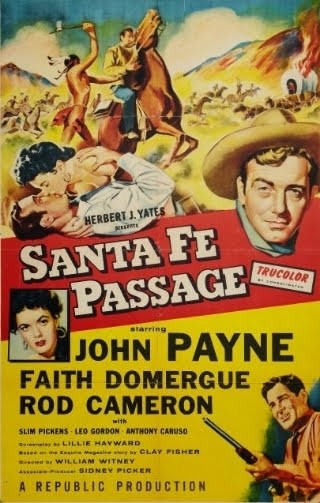

Rod Cameron is third billed but has the leading role. He provides a strong physical presence, although he does end up on the receiving end of a terrific beating meted out by Duryea at one stage. His acting is adequate overall, but the way his character is written is problematic. I think it’s clear enough that the intention is for a redemptive arc to be traced, which is fine as far as it goes. The thing is though that, as written, Corrigan isn’t really a likeable figure for much of the film’s running time. He’s not just a man who is on a learning curve, he’s downright unpleasant to the women in his life and comes across as spoiled and petulant instead of grittily independent. Duryea, as the villain of the piece, actually brings more nuance and therefore more interest to his part. I suppose it comes down to the fact that Duryea, even when we was showboating shamelessly or backstabbing with the worst of them, had a soulful air about him. Top billing went to Yvonne De Carlo but she is off screen for far too long and her role ends up largely undeveloped. Helena Carter is her romantic rival for Cameron’s affections and actually gets the more rewarding part. In support, John McIntire, Florence Bates and Jack Lambert all have their moments.

As a Technicolor production, River Lady might be expected to look better than it does. I have a German DVD that is acceptable all told, but there is a certain muddiness to it too. Perhaps the fact the movie is part of a George Sherman box that has it packaged alongside solid Blu-ray versions of The Last of the Fast Guns and Red Canyon serves to draw attention to its weaknesses.

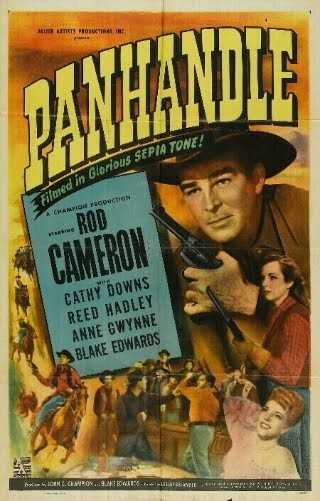

Certain plot devices come up time and again in westerns, so much so that they can start to feel like old friends after a while. On occasion we even get a whole cluster of them all intermingled in one movie, although one tends to dominate when such a situation arises. Panhandle (1948) blends together the tale of the town tamer, the outlaw forced back into his old ways, and the perennial matter of settling scores. It’s that latter element – the quest for revenge, or perhaps it would be more accurate to talk of justice here – that comes to the fore in another stylish example of Lesley Selander’s work.

Certain plot devices come up time and again in westerns, so much so that they can start to feel like old friends after a while. On occasion we even get a whole cluster of them all intermingled in one movie, although one tends to dominate when such a situation arises. Panhandle (1948) blends together the tale of the town tamer, the outlaw forced back into his old ways, and the perennial matter of settling scores. It’s that latter element – the quest for revenge, or perhaps it would be more accurate to talk of justice here – that comes to the fore in another stylish example of Lesley Selander’s work.