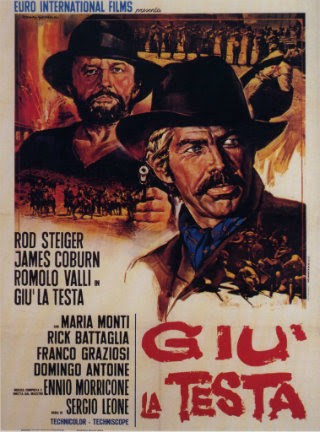

If there are really only seven basic plots or stories then that probably explains why remakes, which are practically as old as cinema itself, are so common. From a business perspective, something that has proven to be successful once may well do so again so the temptation is always there to take another trip back to the creative well. In among the virtual ocean of remakes there is to be found a more exclusive subset, that of a director redoing his own earlier films. Filmmakers as diverse as Alfred Hitchcock, Raoul Walsh and George Marshall did this over the course of their careers. In two of those cases ,The Man Who Knew Too Much and Colorado Territory, I know I like the later films better and if I wouldn’t go quite so far with Marshall’s Destry, I still feel it’s a worthwhile movie. In 1956 John Farrow remade his own Five Came Back (1939) as Back to Eternity, but I can make no comment on how it stacks up against its first iteration for the simple reason that I’ve not seen the earlier version.

The “stranded in the wasteland” story is one which is ripe with possibilities. It promises danger, excitement and suspense, it allows for drama to grow out of shifting group dynamics, it acts as a platform for endurance and ingenuity, and it can also easily blend in themes of spirituality and even notions of redemption. Back from Eternity manages to combine all of those elements in its sub-100 minute running time. The first half hour or so is given over to the kind of character introductions that are necessary. Thus we see the eager new pilot (Keith Andes) and the older flyer (Robert Ryan) weighed down by the accumulation of a lifetime’s emotional baggage as well as a fondness for the whiskey bottle. There is a glamorous refugee (Anita Ekberg) now discarded by her shady lover and on her was to an even shadier future in what sounds like a South American bordello. Among the others there’s a brace of couples, one young and contemplating marriage (Gene Barry & Phyllis Kirk) and the other old and devoted (Beulah Bondi & Cameron Prud’homme), and a political assassin on his way to face execution (Rod Steiger). When a violent storm forces their plane down in the middle of an unexplored jungle in headhunter country, the real drama kicks in. They say that a crisis brings out the best and the worst in people and that is seen to be so here, selfishness and selflessness clashing like a couple of ethical knights in a jousting match of the conscience. Casting people back into a primal landscape and circumstances peels away their civilized veneer and reveals the true characters beneath. Everything comes to a head when the plane has been patched up but only to the point where it is capable of safely taking off and staying in the air with just five people on board. The question naturally arises as to who will go and who will stay, and all the while the unseen threat in the jungle inches ever closer.

Back from Eternity was scripted by Jonathan Latimer, a man who wrote a good many screenplays which John Farrow directed. He was a fine novelist too and his Bill Crane mysteries are a real delight and are highly recommended. As a novelist he was adept at weaving a rich thread of humor into his hard-boiled setups, however there is none of that on display here. Instead, there is a strong flavor of what I think of as Farrow’s influence. He was a director who frequently evinced a noticeably spiritual side to his work and it is clear to see in this movie. Aside from one overtly religious scene, there are the allied themes of sacrifice and redemption coursing through the fabric of the narrative. This is placed front and center in the decisions taken and the character arcs traced by the elderly Spangler couple and Rod Steiger’s Vasquel. It can be glimpsed too in the change of heart experienced by Jesse White’s former hood, in the renewed hope and motivation which stirs in Ryan’s disillusioned pilot, and also in the maternal protectiveness that a new found sense of responsibility draws forth in Ekberg.

All of this lends substance to the story, although it should be noted that it doesn’t arrive at the expense of the tension or danger that sustains the interest of the viewer. William C Mellor does some fine things with the lighting in the airplane and jungle scenes and I feel Farrow was wise to keep the headhunters off screen throughout. We only see the results of their handiwork on a couple of occasions and the rest of the time their oppressive presence is indicated only by the softly ominous beat of drums and a brief glimpse of a hand brushing aside some vegetation – out of sight yet very much on our minds.

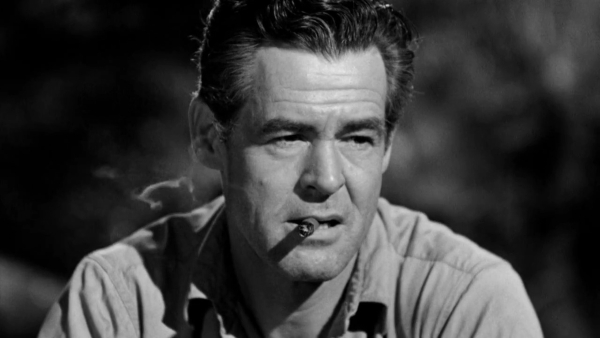

What then of the acting? Rod Steiger is nothing if not interesting, a performer steeped in the Method and one who has garnered both fulsome praise and scathing criticism. Humphrey Bogart said his technique was of the “scratch your ass and mumble” variety, yet he was nominated for an Oscar in On the Waterfront, won one for In the Heat of the Night and did some remarkable things on screen in The Pawnbroker. Like him or loathe him, he was a talent, but he too often abandoned all restraint and seemed to tear movies apart with the sheer artificiality of his work. Fortunately, he holds himself in check in Back from Eternity, operating within his boundaries instead of trashing them. His one indulgence is his adoption of a frankly bizarre accent, a weird type of strangled German or middle European effort that calls unnecessary attention to itself. Robert Ryan is very subdued as the pilot, disenchanted and with a cool noirish cynicism, but never despondent. Anita Ekberg is largely decorative, a pleasingly pneumatic presence and Phyllis Kirk comes over rather starched and stuffy in comparison. Gene Barry is pretty good too as a slick type who quickly sees the polish wear off when he’s in jeopardy – it’s not at all a sympathetic role and I always admire actors who have the guts to take on that kind of part. Generally, the cast turn in professional work and all of them have their moments.

Back from Eternity was released by Warner Brothers on DVD as an Archive title. It looks solid throughout, presenting a crisp widescreen image which is in good shape overall. As I said at the top of this piece, I’m not in a position to draw comparisons with Farrow’s first go at telling this story, but I hope to get to that movie at some stage. Anyway, I’m a believer in taking films on their own terms and merits, and I can only say that I enjoyed this one.