“Nothing is more wretched than the mind of a man conscious of guilt.”

Titus Maccius Plautus

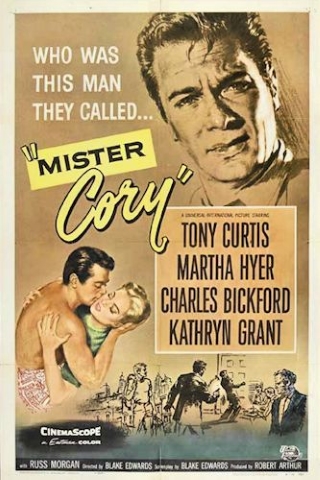

Guilt, doubt and suspicion are some of the key ingredients of dramatic tragedy. One of Aristotle’s four pillars of tragedy is suffering and the aforementioned features can certainly be said to form the basis of that. The concept of guilt runs all the way through The Midnight Story (1957), every major character is assailed by this feeling as it hounds, worries and tears at them insistently. Of course all tragedy really only has a point if it follows its natural path towards a sense of catharsis, a relief or clearing up granted to the characters, not to mention the audience, a lightening of the dramatic load. If guilt and all its gnawing associates can be viewed in a classical context, it can also be seen in religious terms too, especially from a Catholic perspective. In such cases the catharsis we move towards is frequently expressed as a form of redemption. The Midnight Story manages to fuse all of these ideas into a beautifully constructed film noir that draws the viewer deep into dark and despairing places before finally emerging in a brighter, more hopeful landscape.

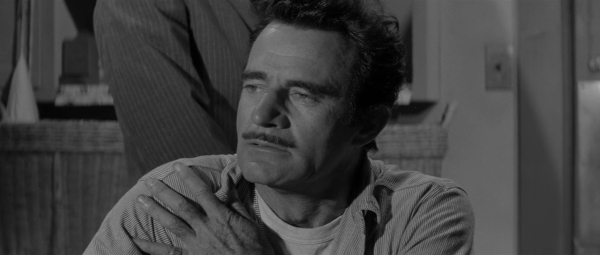

The opening is stark and shockingly abrupt, the caption informing us that the studio set represents an approximation of a side street on the San Francisco waterfront. A priest strolls out of the shadows towards the camera, his attention suddenly caught by a voice softly calling his name. We zoom in on his eyes as they register curiosity, maybe recognition and a touch of fear. This is Father Tomasino and we’re witnessing his final moments as a knife-wielding assailant, seen only as a shadow cast against the tarpaulin of a truck, strikes him down. It’s one of those crimes that outrages people, particularly those who knew and respected the victim. One such person is Joe Martini (Tony Curtis), a young traffic cop who grew up in an orphanage and owes his job and much besides to the murdered priest. Martini wants the killer and he vainly presses his superiors to let him in on the investigation. At the funeral he notices a man who seems to be more deeply affected, tormented even, than the other mourners. There is something about the intensity of this man’s grief that gives Martini pause and indeed leads to him temporarily turning in his badge in order to pursue his own inquiries. The person who has attracted his attention is Sylvio Malatesta (Gilbert Roland), the owner of a seafood eatery and a familiar figure on the waterfront. Deftly and swiftly, Martini inveigles his way into Sylvio’s life, becoming a friend, employee and even a guest in his home.

Guilt haunts the characters from start to finish. There is obviously the overarching guilt that stalks whoever the killer may be, but Martini carries it with him too all the way. As has been stated, he owes almost everything to Father Tomasino and there is surely a sense of guilt that, despite his job as a protector of society, he was unable to be there to ensure the safety of this man. One of the orphanage nuns he speaks to advises against going around with hate in his heart, but I’d argue that his guilt and shame, a feeling of inadequacy (albeit misplaced) due to his not being there at the crucial time, is his true motivation. Then that same feeling steals over him as he works his way into the affections of not only Sylvio but his family too. This is exacerbated by his falling for Anna (Marisa Pavan), the niece from Italy, and her clear devotion to him. All of this is further heightened by the accompanying doubts and suspicions: suspicions about Sylvio that ebb and flow with the depressing regularity of the ocean tides, and those corrosive doubts about the propriety of his own actions, the dubious morality of exploiting the love and trust of innocents regardless of the cause which is supposedly served. Soon every look and gesture is brought under the microscope, no word or comment is so trivial as to be discarded, no alibi can be relied upon or taken at face value. Everything has to be questioned, everyone suspected in some way. And still the guilt persists.

Besides probing its central theme, The Midnight Story functions both as an engrossing whodunit and as a snapshot of working class family life. There is irony in the fact Martini has only been able to achieve the bonding and acceptance that grows out of membership of a family though deception. In seeking justice for the death of his mentor and friend, not to mention a quest to make amends for imagined failings, Martini risks the loss of all that he most desires. The notion of only being able to win by losing everything is a sour-tasting one indeed. Consequently, there are moments of genuine, heartbreaking darkness in this movie, although it does aim for a redemptive quality, and I think it succeeds in that respect. The crushing burden of guilt is finally lifted in the end by the confession and then the quiet nobility of the final scene, where the feelings of the innocent are spared, absolving them of further undeserved shame, Martini simultaneously washing away his guilt for the deceit perpetrated.

I think it’s fair to say The Midnight Story is Joseph Pevney’s best film. Working from a story and script by Edwin Blum (The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes, Stalag 17), he clearly had an affinity with both the themes explored and the subtle blend of film noir and melodrama. Those intimate little scenes in the Malatesta home, often around the dinner table, but not exclusively, reveal some fine character work from a hard-working cast. The spiritualism inherent in the story and its development is never far from the surface, sometimes overtly but frequently buried a bit deeper in the rambunctious and passionate instances of simple family interaction where the real sense of redemption resides and thrives. The final fade out encapsulates that eloquently as inner strength, belonging and renewal all collide and give meaning to everything that has gone before on screen.

Once again, Tony Curtis is given the chance to prove how adept he was at straight drama and he carries it off successfully. I have probably mentioned this before, but I think it’s worth restating: when actors gain a reputation as skilled light entertainment or comedic performers they seem to get stuck with that label and regarded as capable of only that type of work. Sure some play up to it, and Curtis did choose poorly in his later roles yet it seems a pity that his dramatic work, which is generally very strong, is neglected or at best downgraded as a result. The sincerity and determination of his character is never in doubt and he handles the ups and downs experienced, depending on how his investigation happens to be progressing, most convincingly. Marisa Pavan, who only passed away last December, is very soulful and controlled as Anna. It is this control and emotional caution she displays that gives added fire to the scene where she succumbs to her true feelings as the dangerous game her betrothed appears to be playing is laid bare. There is solid support from Ted de Corsia and Jay C Flippen as the senior cops, the former typically bullish and aggressive while the latter gives another of his slightly dyspeptic avuncular turns.

And that leaves only Gilbert Roland. His was long career and one which saw him get better as the years passed. The leading roles were not to be his at that stage but the presence of the man lent gravitas and truth to many a film. The part of Sylvio Malatesta was an extraordinarily difficult one to carry off, but he does so with considerable aplomb. While there is plenty of scope for his trademark bravura, the part is in fact complex and multi-layered, gradually revealing itself in increments over the course of the movie. The inner torments of the man, the history he hauls around inside himself, are subtly presented, held carefully in check and only occasionally allowed to make their presence known. Frankly, he gives a beautifully judged performance that is fully three dimensional – his work here is the rock which anchors the movie and provides real substance to the story.

This brings me to the end of my trawl through a selection of Joseph Pevney directed movies this summer. It’s something I’ve been wanting to put together for a while now and I’m pleased to have finally done so. I only hope it’s been as enjoyable for visitors to follow along as it has been for me watching and writing about these titles.