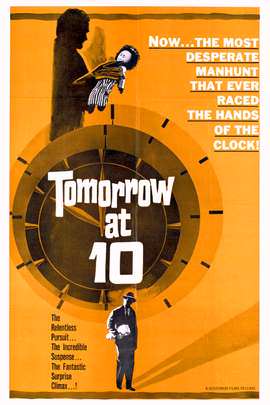

Finding myself writing about a lot of crime movies of late, I consequently find myself ruminating over what goes into making these genre pieces successful. Well of course it is a combination of writing, acting and direction, with a some additional assistance from sets, photography and music from time to time. Still those are broad terms which encompass a lot, but I think one critical element that grows out of their synergy is what we term suspense. The best examples of the crime movie trade heavily on this, using it to hook and then captivate the audience. Tomorrow at Ten (1963) is a first-rate British crime picture that does this in superb style.

Sometimes I think that the worst crimes can inspire the best films. Kidnapping is an especially nasty and traumatic piece of work, putting a life at risk and simultaneously exerting sadistic psychological pressure on those faced with the ransom demands. That’s in real life. However, in the fictional world of the movies the dramatic potential of such situations is practically boundless and, depending on the perspective from which the story is seen, multi-faceted too. Here we are introduced to man calling himself Marlow (Robert Shaw) who is in the process of adding the finishing touches to a meticulously planned scheme; in the secluded house he has rented, we see him happily gutting a child’s stuffed toy and snugly fitting what is clearly a device with a timer. This golly will be used superficially as a comforter for the little boy Marlow will abduct and also as a form of dreadful insurance to secure the cooperation of the victim’s father.

It’s barefaced stuff, snatching the boy and then presenting himself to the shocked parent to calmly demand money and immunity. Marlow is counting on his threats either keeping the police out of the affair or inducing the wealthy father to use his influence to neuter their efforts. But he reckons without the grim determination of DI Parnell (John Gregson), a man with a clear and uncompromising sense of justice. In the finest dramatic tradition though, even the best plans hit snags, and in this case it’s a huge one. In fact, the powerful emotions released by his actions has wholly unforeseen results for Marlow, dragging the story in a different more intense direction and raising the suspense to a completely new level.

Briefly scanning back through pieces I’ve written here in the past and I don’t believe I’ve included any films directed by Lance Comfort yet. Bearing in mind how many of his movies I have to hand, this seems like an odd omission and certainly not an intentional one. Comfort worked in a range of genres but he had a real talent for crime movies and thrillers, and he also managed to wring the very best out of some particularly spare projects. Tomorrow at Ten makes use of a small central cast, around a half dozen people and keeping the focus on Gregson and Shaw in particular. When one thinks of these British quickies there’s a tendency to expect simple and direct visual setups, but Comfort had the experience and the resultant confidence to move his camera around more imaginatively and there are a number of extraordinarily stylish shots on view. And he was a highly professional filmmaker, never losing sight of the thread of the narrative and the necessity to keep everything moving relentlessly towards the resolution.

Robert Shaw was one of the big stars of British cinema, although he had yet to make his major breakthrough – that was to come shortly with his portrayal of the cold and dangerous Red Grant in From Russia With Love. As an exercise in frighteningly psychopathic behavior, Tomorrow at Ten provided a pretty good warm-up, allowing him to create a genuinely memorable villain – there’s something chilling about his gleeful appreciation of his own cunning. Opposing hm is the stolid and reassuring presence of John Gregson as the dogged and principled policeman. As the plot develops, it’s Gregson who gets the greater share of screen time and he brings the audience along on the emotional journey as he hunts against the clock for the clue that may vindicate his methods and, more importantly, save an innocent life.

Tomorrow at Ten was released on DVD by what was Odeon well over ten years ago. That edition appears to have gone out of print now but, as far as I can see, there should be used copies available to buy for reasonable prices online. The transfer on that DVD was in Academy ration, which is unlikely to have been correct for an early 60s film. There are also some instances of print damage to be seen but overall the presentation is perfectly watchable. The movie itself is wonderful little hidden gem, one where the suspense is increased artfully and built around a mightily absorbing tale. Highly recommended.