My previous post was a brief perusal of two westerns from just before what can be seen as the cut off point for the classic western era. As with most if not all the genre efforts from around that time, there’s that sense of trying to look in two directions at once. If we do take 1962 as marking the last year for the truly classical western, it’s also interesting to look at a movie from that year which not only retains a strong feeling for the legacy of the genre but is also one which cast ahead in a way I increasingly feel was the path that ought to have been followed rather than the self-defeating one that grew out of the Spaghetti and revisionist versions. The film in question? Lonely Are the Brave.

The opening scene perfectly encapsulates the paradoxical situation at the heart of the story. Is there anything more evocative of classical western imagery than that of a weary rider stretched out on the open plains, resting up after a hard ride and a long day, gently warmed by the glow of the camp fire he’s built next to him – a man at peace and to all intents and purposes practically a part of the landscape he inhabits and works? And then the jarring intrusion of the modern world, the boom and roar overhead, drawing our eyes and his upward to focus on vapor trails carved across the sky by a passing jet aircraft. The message is simple: the world has changed, inevitably so, morphing into one of noise and urgency, where the travails and pleasures of an earlier time have been supplanted by an updated variety, and the only frontiers still unconquered are those the marvels of technology haven’t quite reached yet. All of that raises a question too, namely whether these two perceptions of the world can co-exist, or whether one must naturally wipe away the other. By the end, the latter is very strongly indicated, but I’m not sure if Dalton Trumbo’s script has entirely closed the door on the former. Even in the ultimate tragedy lies a grain of hope, and perhaps no more than half a grain at that, reflected in the bittersweet admiration of a lawman who sees the futility and waste in the contemporary world’s need to impose itself on a free spirit. One could argue that the last shot heard in the movie represents the one which killed the western, a coup de grâce for a genre which was about to slip into sharp decline. I do think that is mainly what Trumbo was expressing, although I also reckon he left the door not quite ajar but still open just a crack.

“A westerner likes open country. That means he’s got to hate fences. And the more fences there are, the more he hates them…Have you ever noticed how many fences there are getting to be? And the signs they got on them: no hunting, no hiking, no admission, no trespassing, private property, closed area, start moving, go away, get lost, drop dead!”

Whatever one’s opinion of the destination, the journey that gets us that point is a fascinating elegy to a myth. If the myth of the Old West had any meaning, it was as a celebration of freedom. Like all myths, however, this cannot be entirely true. Unfettered freedom is neither practicable nor possible once populations grow beyond a given point and societies, even on a rudimentary level, take hold. In the final analysis, there’s no getting away from the truism that one’s freedom extends only to the point where someone else’s begins. All of this is part of what makes the western such a compelling narrative vehicle. The entire concept has conflict built in, and conflict is the essential ingredient of drama after all. So many westerns have had as their foundation the idea of fences, be they physical or mental.

Jack Burns (Kirk Douglas) is one of the last holdouts against the relentless encroachment of contemporary life and the fences it brings with it. The first glimpse of the man confirms the impression of someone who is a walking anachronism. The attitude, appearance and lifestyle hark back to a time long gone, and his bemusement at the clamor and restrictions of the world around him makes the viewer wonder whether it’s one he has been dropped into rather than grown up with. His almost comical effort to navigate an insanely busy highway foreshadows the deeply unsettling conclusion of the picture, but it also serves to underline just how out of his depth this man is in the latter half of the 20th century. The film throws out these contrasts all the time – the way Burns is befuddled, abused and finally struck down by the brute force of modernity, juxtaposed with those scenes showing him in his element, resourceful and formidable in circumstances that favor his talents. Sure he sets himself up for difficulties in his efforts to make contact with his imprisoned friend (Michael Kane) but the way he falls foul of a bitterly aggressive one-armed man (Bill Raisch of The Fugitive) and then George Kennedy’s sour and sadistic jailer are more the result of his unfamiliarity with a world he shuns.

That world is one made up of prisons of various kinds. There is the literal one where his friend has wound up serving a two year sentence for trying to do the decent thing by some illegal immigrants, plus ça change indeed. Even Walter Matthau’s sheriff seems to spend a lot of time early on framed behind bars, albeit those set protectively into the walls of his own office. Always an immensely crafty performer, Matthau revels in the absurdity of life around him, musing on the enslavement of routine and regulation which even appears to extend to the neighborhood stray who marks his territory with near military precision on a daily basis. It’s a lovely character sketch, by turns dyspeptic and droll, and satisfyingly empathetic by the end.

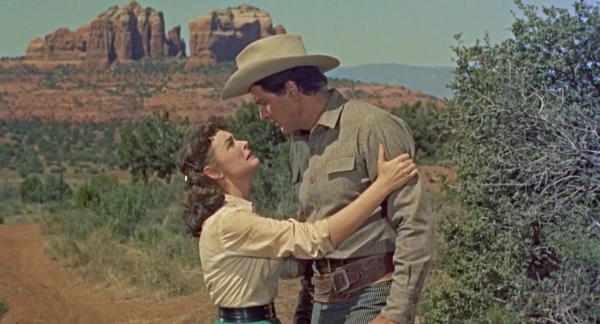

Then there are the virtual prisons, those of their own making, which both Gena Rowlands and Kirk Douglas inhabit. She has locked herself into a marriage with a man who, by her own admission, she probably only half understands and from whom she is now unwillingly estranged due to his incarceration. Her affection, and maybe more, for Douglas is always apparent though in the little looks and gestures. The same applies to Douglas himself, the untamed loner who, like it or not, knows he’s beyond the point where he can change. In a movie ripe with poignancy, the touching little scene played out on the porch of Rowlands’ house before Douglas departs for the last time is superb – regret, longing and a love acknowledged and treasured yet still resisted all combine beautifully.

“Jack I’m gonna tell you something. The world that you and Paul live in doesn’t exist, maybe it never did. Out there is a real world and it’s got real borders and real fences, real laws and real trouble. And either you go by the rules or you lose. You lose everything.”

There is a great deal of loss in the film. At various points, dignity, freedom, and eventually even that tenuous hold we try to maintain on the past all are wrested from the grasp of the characters. This should mean it’s all relentlessly downbeat, but there are genuinely uplifting episodes sprinkled in among the grimmer ones. Douglas’ struggle up the rocky mountainside is an epic affair where his grit and cunning is put on trial repeatedly. It carries some of that Anthony Mann symbolism in the upward thrust, and the moment when he finally crests the peak and spurs “Whiskey”, his stubborn and recalcitrant mount, towards the treeline on the other side and the promise of salvation is truly joyous. What follows shortly afterwards is heartbreaking of course, but that neither negates nor dilutes the emotion captured in that instant.

So where does all this leave the movie within the genre’s evolution? As with the other great westerns of 1962 – here I’m thinking specifically of Ride the High Country and The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance – a line is drawn beneath the genre, a sense of closure achieved. It makes its point about the doomed romanticism inherent in looking back, and if it doesn’t look ahead with positivity, it does underline the fact that progress cannot be halted. I found it interesting too to note that although the director of the movie David Miller was not someone associated with westerns – the only other he made was Billy the Kid decades earlier – it stands out as his best piece of work. I have wondered before now whether the western wouldn’t have been better served exploring its core themes in a contemporary setting once the classical era had passed, and it’s an idea I continue to find intriguing. Maybe the fact that recent years have seen the contemporary western enjoy considerable success via television, ironically the medium that once contributed to its slow demise, provides proof of that?

As an Amazon associate, I earn from any links to Amazon followed from the post or from comments below.