It’s just a case of too soon old and too late smart.

Choices and chances – life offers its fair share of both to all of us as it meanders along, and the way we react to them is frequently determined by timing. This could be regarded as no more than everyday stuff, but all good drama has such apparently mundane concerns as its foundation. In fact, the best examples of drama all have a timeless quality, containing some basic truth that transcends their age. Westerns, one could argue, are very much rooted in the time period they depict. Again though, the best western movies have at their core a theme that goes beyond time and place, one which addresses contemporary issues while also remaining relevant to modern life. Will Penny (1968) is one such film, focusing on a set of circumstances arising directly from its Old West setting, and also speaking to audiences of matters that are constants of the human condition.

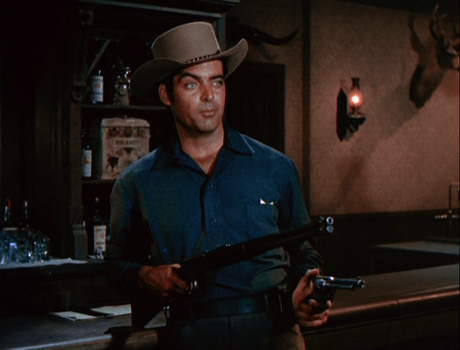

Will Penny is a film that can be approached, and which works, on three different yet interrelated levels. It’s an absorbing adventure, an examination of a way of life approaching its twilight stages, and a tale about the power and promise of human relationships. Will Penny (Charlton Heston) is the archetypical western hero, a man alone, a self-reliant and capable character shaped by the landscape he occupies and the job he does. But Will is a man who’s growing old and, like the frontier itself, is fast approaching a point where he is going to be consigned to the past – tellingly, he’s the only rider at the end of the round-up who is illiterate to the extent he has to sign his name by marking a crude X in the ledger. Whatever the reality may have been, the fictional cowboy has always been a figure of nobility, a kind of latter-day knight bound by a personal code of honor. The first example of this, and also the first of a number of fateful decisions taken, comes when Will passes up the opportunity to move on to Kansas City and continued employment to make way for a younger man who wants to see his ailing father. Instead, Will sets off with two companions (Anthony Zerbe & Lee Majors) with only the slimmest of hopes of finding work to see them through the winter. In the course of their journey two significant events occur, one leading on directly from the other. Firstly, a fatal misunderstanding over the shooting of an elk sparks a feud with a crazed old man, Preacher Quint (Donald Pleasence), and his degenerate family. This violent encounter leaves one of the men seriously wounded, and necessitates a stopover at a remote swing station. It’s here that the seeds of the second, and more interesting strand, of the story are planted. Catherine Allen (Joan Hackett) is traveling west with her young son, and Will has his first, semi-comedic, meeting with this slightly prim woman as he tries to secure medical attention for his wounded companion. We come across all kinds of people all the time, and Will naturally thinks nothing more of it. However, having found employment as a line rider for a nearby ranch, Will chances upon the woman a second time, now occupying the cabin assigned to him for the long winter months ahead. Despite having explicit instructions to ensure that travelers must move on as soon as possible, Will lets his innate nobility get the better of him once again. His decision to let the woman and her son stay on till spring, coupled with the fact that the Quint clan remain loose and thirsty for revenge, is to have a profound effect on Will’s whole take on his life. As I said in the opening, everything boils down to chances, choices and timing.

Before 1968 Tom Gries worked extensively on television, and Will Penny – which he both wrote and directed – allowed him to break through into the cinema. It remains his best piece of work, mainly due to its authenticity. The movie captures the look and feel of its era very successfully – the loneliness, the drudgery of everyday life, and the sense of times changing fast. More significant than any of that though is the authenticity that Gries managed to draw from his characters and how they related to one another. It often feels like romantic sub-plots are injected into dramas almost as an afterthought, and consequently seem fake, forced and superfluous. Here however, the relationship that gradually builds between Will and Catherine, and her son, constitutes the beating heart of the picture. This touching and deeply affecting portrayal of lonely people glimpsing an opportunity for love and companionship is the factor that raises Will Penny up and lends it that timeless quality I referred to earlier. Historically speaking, Will Penny occupies that nebulous zone, as do many westerns of the 60s, straddling the classical and revisionist periods. The clear delineation of heroes and villains, and the focus on a kind of selfless nobility hark back to the likes of Shane and Hondo from the preceding decade. On the other hand, there’s also that melancholy feeling of a disappearing era that would be explored further in films such as Monte Walsh and Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid in the years to come.

Will Penny features a first-rate cast, and I don’t believe there’s a poor performance anywhere – Ben Johnson, Donald Pleasence, Slim Pickens, Bruce Dern, Lee Majors and Anthony Zerbe all do good work. Having said that, both Charlton Heston and Joan Hackett seem to connect with their respective roles in a way that elevates them far above those all around them. There are those who would assert that Heston wasn’t much of an actor – similarly ill-informed accusations are often leveled at John Wayne and Gary Cooper – and was more of an icon than a performer. In Heston’s case, this probably comes from his frequent casting as larger than life heroic figures. Will Penny saw him playing a simple human being though, the most reluctant of heroes, and was reportedly his favorite role. Heston gets deep inside his character here, investing him with an astonishing level of credibility. There’s genuine modesty on display, a kind of faltering fallibility about this performance that can be seen in all kinds of ways – the barely concealed shame over his illiteracy and lack of education, the physical suffering he undergoes, and his struggle to come to terms with an emotional awakening that has taken him completely by surprise. Joan Hackett didn’t possess traditional Hollywood glamor, but she too reached inside to find an inner truth that characterizes her performance. The fact that Heston was able to produce something so touching is largely down to Hackett’s playing opposite him. For me, there are two standout scenes: that sweet and beautiful business involving the Christmas tree and the boy; and the climactic scene in the cabin where Hackett and Heston bare their souls and break your heart. The resolution of the movie could be seen as a firm rejection of the standard happy ending, but that doesn’t necessarily mean it’s a downer. Personally, I like to think of it in positive terms; the overriding message for me is that there’s always hope for even the loneliest and unhappiest individuals. Whether one seizes that hope is, of course, another matter entirely.

Will Penny is a Paramount picture and the UK DVD, despite being released a long time ago now, is still a very strong disc. The film is given an excellent anamorphic widescreen transfer with natural colors and was obviously taken from a very clean print. There are two short features included on the casting and making of the film, with contributions from Charlton Heston and Jon Gries, the director’s son who also played Joan Hackett’s little boy in the movie. Will Penny probably represents Charlton Heston’s finest screen work, and the film is an immensely satisfying experience. It’s thoughtful, mature, at times exciting, and always affecting. For anyone who has yet to see the film, I recommend it wholeheartedly.