“What do you Yankees think you are? The only real Americans in this merry old parish are on the other side of that hill with feathers in their hair”

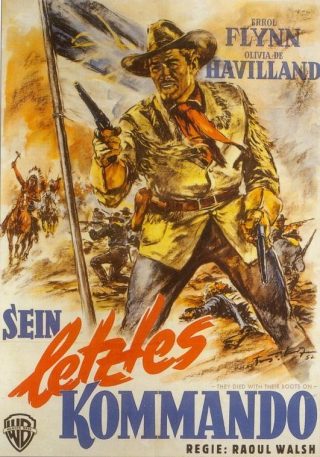

If most old movie fans were asked to name their favorite Errol Flynn picture I think that a significant majority would probably plump for The Adventures of Robin Hood. I couldn’t really fault that choice as it comes in near the top with me too, but it’s still not my favorite. That honor would have to be reserved for They Died with Their Boots On (1941). I don’t know if it’s Flynn’s best film but it is up there and must surely be seen as one of the high points of his career. The character of George Armstrong Custer is one that Tasmania’s most famous son must have seemed ideally suited to playing. When the film was made Custer’s reputation as one of America’s greatest military heroes was only beginning to be reassessed, so there’s no axe-grinding revisionism to be found. Judged as a faithful biopic or character study, the movie is open to all sorts of criticism; but that’s not really what They Died with Their Boots On is all about, and it would be doing it a great disservice to treat it too harshly on those grounds. No, this is a Boys’ Own adventure of romance and daring, of guts and glory – and taken as such, it works perfectly.

There have been numerous portrayals of Custer on screen, dating back to Francis Ford in 1912, but I doubt if any have imbued the man with the glamour that Flynn brought to the part. The film traces his life and career from his entry into West Point up to his final moments at the Little Big Horn. Custer’s arrival at the US military academy, in all his gold-braided glory with a pack of hunting dogs in tow, is largely played for laughs, although it does set up a simmering rivalry with fellow cadet Ned Sharp (Arthur Kennedy) that’s crucial to the plot’s development. In fact, this is a film of two distinct parts; the first hour or so is mostly lighthearted knockabout stuff with only the occasional foray into more serious matters, while the second half takes on a decidedly darker and moodier tone. Therefore, we get to see Cadet Custer as a kind of fun-loving prankster who liked to ride his luck and chance his arm with authority, which, by all accounts, wasn’t too far from the truth. When the Civil War intervenes and necessitates his early graduation, Custer finds himself torn between pursuing his interest in the love of his life, Libby (Olivia De Havilland), and his enthusiasm to get into the thick of the action. Naturally, the pursuit of glory and honor wins out, and this leads to a nice little scene in Washington with General Winfield Scott (Sydney Greenstreet). Interestingly, Custer did have a fortuitous meeting with the Union commander on arrival at the Adjutant General’s office which led to his first active posting – albeit without the business with the creamed onions. The war, which ironically brought enormous fame to Custer, is given only minimal attention but it does show his rapid rise through the ranks. While all this is presented in a highly entertaining fashion, you still get the sense that we’re only marking time until we get to the real meaty stuff – the move west and the Indian Wars.

With the action shifting to Dakota, the whole feel of the film changes and raises it up to a different level. There’s still time for the odd lighter moment but it’s quickly apparent that this new war is no gentleman’s affair. Custer almost immediately clashes with his old foe Sharp who’s running a saloon and trading rifles with friendly Indians from within the fort. The first order of business is to end the drinking and whip the drunken recruits into some sort of fighting force. This is achieved via a wonderful sequence whereby Custer adopts the old Irish drinking song Garryowen and uses it as a means of instilling a sense of pride and unity into his ragtag 7th Cavalry. There’s also the first view of the red men, and in particular their chief Crazy Horse (Anthony Quinn). One notable aspect of this movie is the respect afforded to the Sioux; at no point are they portrayed as anything less than a disciplined fighting force with legitimate grievances. The real villains of the piece are the corrupt officials and their businessmen backers from the east. The point is made very clear that the Sioux are left with no choice but to rise against the whites when treaties are broken and their shrinking homeland is further encroached upon. When Custer leads out his last fateful expedition he does so in the hope of earning more personal glory of course, but it’s also obvious that his political masters and their moneyed allies have left him with no other option. So, he leads his 7th to the Little Big Horn – to hell…or to glory, depending on one’s point of view.

Flynn gave one of his better performances in They Died with Their Boots On, particularly in the second half. You can see the character gradually mature as the story moves along, his youthful optimism giving way first to disillusionment and then, finally, to a perversely jaunty death wish. If you wanted to stretch a point, it’s possible to see parallels in the course of Flynn’s own life. There’s also much more maturity in the relationship between the characters of Flynn an Olivia De Havilland; this would be their last film together and that fact adds considerable poignancy to their farewell scene, which is pitch perfect in its playing. However, even though the film marked the end of one partnership, it would signal the beginning of another – this was the first movie that Flynn made with director Raoul Walsh. If the star’s relationship with Michael Curtiz was a less than happy one, his collaboration with Walsh was much more congenial. These were two men who were much closer in temperament and Flynn seems to have felt a lot more comfortable in the company of the buccaneering old director. Walsh was one of those directors who was always in his element shooting outdoors on location. I’ve already made the point that when the film switches to the west it moves up a gear, and I think that’s due, in part, to Walsh’s affinity with the outdoors. The last half hour or so has a dreamy, poetic quality that’s the equal of some of John Ford’s best work – and that’s no mean feat. It should also be pointed out that the movie benefits enormously from one of Max Steiner’s finest and most memorable scores, which is built around the rousing yet vaguely melancholy Garryowen.

Warner’s R1 DVD (I believe the R2 is the same transfer) of They Died with Their Boots On is quite fabulous, clean and sharp with barely a damage mark in sight. It has a good selection of extras though it lacks a commentary, which I feel this movie deserves. OK, maybe this isn’t the best western you’ll ever see but it’s right up there among my all time favorites – one of those films that unfailingly pushes all the right buttons on every viewing. Next up, San Antonio.