A lot of you all rode into this town, but you are the only one who saw anything. You noticed the change. The others don’t look past the end of their guns. You saw the handwriting on the wall. They don’t even see the wall because their backs are against it. Their days are over. They don’t know it.

Sometimes I like to open with a quote that in some way sums up the tone, mood or message of a given movie. In this case, those lines above represent more of what I feel the film could have been as opposed to what we actually end up with. City of Bad Men (1953) is a title which left me feeling not entirely satisfied when I first saw it and so I thought I’d give it another go to see if my reaction would be any different this time. The answer is a kind of yes and no: yes in that I enjoyed it all a little more, but I still came away with that nagging sense of having seen an opportunity missed, or at least not fully grasped.

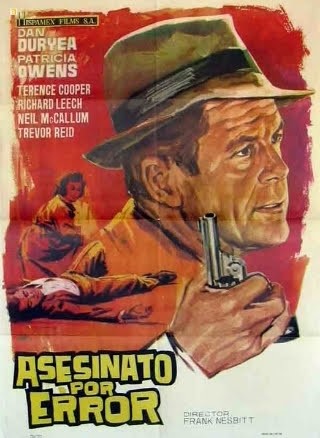

On St Patrick’s Day 1897 in Carson City, Nevada, a fight for the world heavyweight championship (actual footage of the bout can be viewed on YouTube) took place between Bob Fitzsimmons and “Gentleman” Jim Corbett. This event forms the backdrop to and also constitutes a major plot element of the film. Returning from an unsuccessful trip south of the border as soldiers of fortune is a group of weary men led by Brett Stanton (Dale Robertson). With little of worth to show for their time and effort, they are heading for Carson City with the hope of knocking over the bank in what they believe to be a perennially sleepy town. However, the town they ride into has undergone a transformation, partly due to the changing nature of the times but also as a result of the upcoming prize-fight. Yes, civilization and the trappings of the modern age – the motor car and luxuries like the shower – are slowly creeping westward. While his men gaze upon these alien sights with a kind of detached bemusement, Stanton’s calm features mask the fact that the seeds of an opportunistic plan have been sown in his mind. Crowds like this mean money – money which can be made or stolen. Yet Stanton isn’t the only one to entertain such thoughts; other gangs of unscrupulous men, most notably those led by Johnny Ringo (Richard Boone), have been drawn by the prospect of easy pickings. The local lawmen realize the volatility of such a situation and hit on the novel idea of appealing to the mutual suspicion of these various desperadoes and convincing them that the best way to keep the peace (and thus protect their own mercenary interests) is by keeping an eye on each other. Stanton is smart enough to see the advantages of such an arrangement, but he’s also aware of the complications and obstacles ahead of him: the need to come up with a viable plan to pull off a spectacular heist, the latent jealousy of his brother Gar (Lloyd Bridges), and the feelings he still nurses for the girl (Jeanne Crain) left all those years ago.

As I see it, there are four major themes at play in the movie – the noir-tinged heist plot, the classic idea of changing times, the sibling rivalry, and the notion of redemption earned through love. Lots of material to chew over yet only one, the heist aspect, is realized fully and successfully. The fact the script allows this to develop naturally and then the way Harmon Jones directs its execution, cutting between the fight, the collection of the takings and the way the money is subsequently lifted, is a fluid and assured piece of filmmaking. It makes for a fitting climax to the picture, but also highlights the deficiencies in the handling of the other facets. The early scenes give the impression that the “men out of time” part will be of greater importance, but it’s something the film only pays lip service to in reality. Similarly, the tension between Brett and Gar is never fully explored and its resolution feels rushed in the end. As for redemption, which ought to form the centerpiece of a western of this era, I was left feeling that it’s achieved a touch too easily, and the means by which it’s linked to Brett’s reconciliation with his old flame is weakened by its abruptness. I guess what I’m trying to say here is that the film has a strong foundation with a number of rich veins running through it, only few of which are mined and even then not to their full extent.

When called upon to do so, Dale Robertson was good at conveying cold intensity but that wasn’t really a requirement in this role. He displays the necessary toughness to hold the whip hand over his own bunch of ne’er do wells and to keep his rivals in check. Essentially though, the part of Brett Stanton is all about calmness, a kind of melancholy thoughtfulness. His air of regret and his flexible morality tie in with, and feel like an extension of sorts of, the type of disillusioned veterans so common in film noir, bewildered by and isolated from the new world they find themselves confronted with. For me, Robertson’s quietness and restraint is one of the major strengths of the picture. Ranged against that is the restlessness and impatience of Lloyd Bridges and, more significantly, the rattlesnake charm of Richard Boone. If anything, Boone is underused in the movie, lighting up the screen every time he appears while leaving you disappointed he’s not there more. Which brings us to Jeanne Crain – her character is a vital one through the effect she has on Robertson, but the script doesn’t treat her well. She’s placed in a conflicted position that’s loaded with dramatic possibilities yet her character arc isn’t wholly convincing and the resolution, which forms the core the film’s resolution in itself, is just a little too convenient for my liking. In support, we have Carole Mathews, Rodolfo Acosta, James Best, Leo Gordon, John Doucette and, in blink and you’ll miss them parts, Frank Ferguson and Percy Helton.

City of Bad Men is a 20th Century Fox production and was released on DVD in Spain some years ago by Impulso, licensing the title from Fox. That disc offers a passable transfer which is clearly unrestored. There are a number of instances of print damage and the colors tend to look faded throughout. Having said that, it’s perfectly watchable – there was subsequently a US release by Fox itself, but I have no idea how that transfer compares. The Spanish DVD offers the original English soundtrack along with a Spanish dub and optional Spanish subtitles. Of the Harmon Jones westerns I’ve seen, I’d say this is probably the least of them. I’d certainly rank it below his other two with Robertson, The Silver Whip and A Day of Fury. All told, there are some positive points and the film remains briskly enjoyable. Nevertheless, I can’t shake that feeling that it had more to offer than it ultimately delivered. In the final analysis, a medium effort.