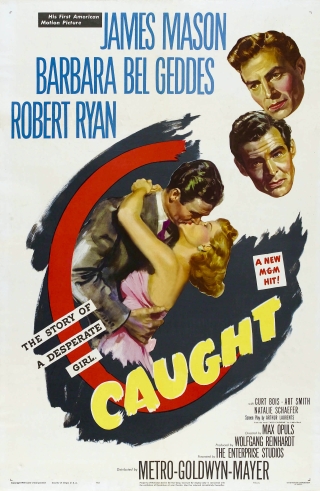

Seeing as Max Ophuls came up in some of the comments on the previous post, I decided to go back and have another look at one of his movies that I have struggled with in the past, namely the 1949 production of Caught. As a rule, I have enjoyed what I have seen of the director’s work, but this film has never worked for me. Anyway, with his name fresh in my mind, as well as the knowledge that the movie seems to be well regarded by many other viewers, I thought I should give it another chance. In brief, and this will be one of my shorter posts, I still have major issues with the movie. To be honest, the fact that I made it to the end was as much through a sense of obligation as anything.

The whole thing is an examination of wish fulfillment and the consequent importance of being very careful indeed of what one wishes for. It opens with two sisters in a shabby tenement mooning over glossy magazines and browsing for dreams, a gem encrusted necklace here, a platinum bracelet there, and so on. As ever, money and the power it bestows matters very much to those who have little of it. Leonora (Barbara Bel Geddes) wants the security and the comfort that comes with wealth, and it does come her way as the result of an invitation to a party on a yacht, an invitation she very nearly turns down. This is the thing with Leonora – she wants things and then doesn’t want them when their real cost becomes apparent. When she makes the acquaintance of Smith Ohlrig (Robert Ryan), a tycoon with a deeply disturbed character, she is soon on the fast track towards the high life on Long Island. However, this is where it all goes wrong for just about everyone involved. Ohlrig is a domineering, controlling and cruel man, an obsessive soul at war with himself and the world in general. Leonora soon comes to see the stew she’s landed herself in and, wisely one would say, moves out and ends up working as a receptionist in a slum neighborhood for Dr Quinada (James Mason). From here the movie devolves into a series of sorties back and forth for Leonora as her indecision along with a deep-seated conviction that she has to “improve herself” at all costs winds up being a good deal more expensive in emotional and physical terms than she’d bargained for.

Max Ophuls’ direction is a pleasure – his camera swooping, swinging and panning, following his characters and sometimes sweeping past them to draw attention to the variously opulent or cheap surroundings while they debate, argue or simply muse out of shot. It’s a distinctive style and Lee Garmes’ cinematography adds to the eye-catching visuals. Attractive as all this may be, it’s not enough to paper over the paucity of genuine character at the heart of the movie. Robert Ryan’s Howard Hughes inspired sociopath is a showy piece of work, neurotic and foul and yet also somehow pitiful in his inadequacy. However, there’s a big hole in the middle of it all for me, and that’s the result of the role played by Barbara Bel Geddes. I started off feeling for her as she struggled to dig herself out of the poverty trap. The fact is though that she’s a playing a woman with essentially no character, a whiny, vacillating type who seems to revel in helplessness and indecision. This is the person who is the main focus and it’s very hard to like a movie where the central role presents such a moral vacuum. And the less said about the “happy ending” we’re asked to buy into, the better. James Mason’s first Hollywood starring role is fair, but he’s given little to do to stretch him – he does have at least one good scene in the garage confrontation with Ryan and Bel Geddes. The support is mainly an attractively homespun turn from Frank Ferguson and a well observed peek at degradation and dissipation by Curt (“Tough, darling, tough.“) Bois.

Max Ophuls made far better films than this – The Reckless Moment, again with Mason, came shortly afterwards and is superior in every respect, and there are his great French movies such as The Earrings of Madame de… and La Ronde. I honestly wish I could like this film more, but it just does not do it for me.