I happened to be involved in an online discussion elsewhere today, and the talk turned to how certain movies can be categorized. To be specific, we were chewing the fat over those films that fall at the extreme ends of the spectrum, the great and the shockingly bad. Now I’ve long been of the opinion that few movies truly belong in either of those positions; the vast majority occupy some kind of middle ground, with some of us drawn to particular virtues that appeal to us while others are less enamored. I’ve pointed out before that I’m a little uncomfortable with the term “masterpiece”, mainly due to all its high-pressure implications, but I’m no fonder of the label “turkey” either. Anyway, all of this put me in the mood to hammer out a short piece on a film that I think it’s fair to call average. Gun Glory (1957) is what I would think of as an extremely typical film, nothing special but entertaining enough and with at least a handful of positive things in its favor.

The return of the prodigal is an ancient story, although the variant in question here sees the father rather than the son cast as the errant figure. Tom Early (Stewart Granger) is a man who abandoned his wife and son, a gambler and gunman of great notoriety. The film opens with this character making his way back towards the home he has long neglected. A brief stop off in the neighboring town shows that his reputation precedes him, but his optimism remains undimmed as he happily purchases a trinket as a gift for his wife. However, his arrival at his ranch brings him down to earth and back to reality with a jolt. His son, Tom Jr (Steve Rowland), is less than impressed, and then there’s the sickening realization that the woman he once loved has passed away in his absence. Still and all, blood ties are powerful and the father and son come to a kind of edgy understanding – the wrongs and mistakes of the past can never be forgotten, but it’s human nature to try to forgive and move on. Therefore, the two men make an effort to piece together their relationship, Tom Sr being especially keen to win back the trust and respect of his son that he so casually squandered before. He even takes in a lonely widow, Jo (Rhonda Fleming), as his housekeeper in an attempt to restore something of a family atmosphere. The western genre is packed with stories of men desperate to outrun their past ans sooner or later these guys come to realize that it’s an impossible task – the past must be faced squarely and dealt with before any door to the future can be opened. In this instance, the past is represented by the arrival of a ruthless cattleman, Grimsell (James Gregory), bent on driving his herd through town and obliterating it in the process. As such, it’s both an opportunity and a challenge for Tom Early Sr – an opportunity to prove himself and do something decent, but also a challenge to his desire to leave his violent ways behind him.

Roy Rowland was what you might call an efficient director of programmers, movies that were a cut above B pictures but just shy of being A list features. He handled a couple of pretty good westerns in the 1950s (Bugles in the Afternoon and The Outriders) alongside a very strong film noir (Rogue Cop). Films like this called for a brisk, no-nonsense style and Rowland was well suited to that kind of role. A good proportion of the action takes place indoors but there are opportunities for location work too, and the director showed that he was more than capable of composing attractive setups for the wide lens. Gun Glory, which was adapted from a novel by Philip Yordan, isn’t one of those non-stop action movies but when it does come along, Rowland shoots it well with a good sense of spatial awareness. More than anything though, this follows the classic 50s western template of a remorseful man seeking to make amends for his errors.

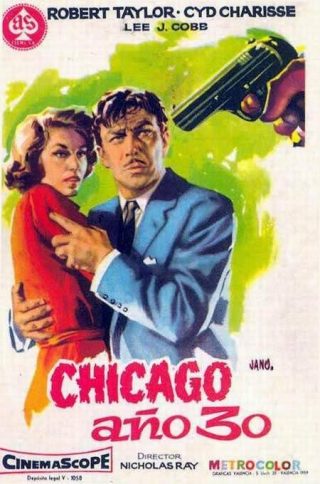

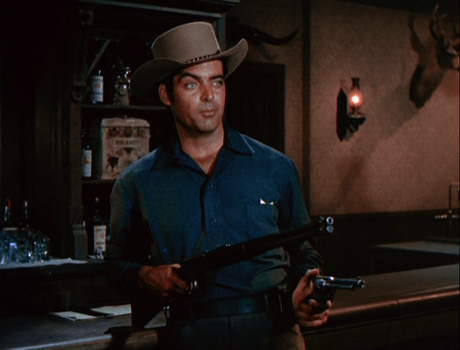

Stewart Granger was building on his successful western role in Richard Brooks’ The Last Hunt which had been made a year before. He seemed very much at ease in the frontier setting, showing off some highly impressive horsemanship skills in the process. In fact, it’s Granger’s strong central performance that is the greatest strength of the film. It’s clear enough that he’s playing a man carrying around a heavy burden of guilt – blaming himself for not being there when his wife died, and for failing to support his son during his formative years – but he never lays it on too thick. Still, there can be no doubt how he feels about himself; the short scenes of him visiting his late wife’s grave tell us all we need to know without the need for dull, expository dialogue. Rhonda Fleming was given a strong part in the movie as the widow who works her way into the lives and hearts of the two Early men. Her role served the important function of drawing both of these men out and helping them achieve a true reconciliation. I think it’s also worth pointing out the romance that develops between the characters of Granger and Fleming is nicely judged, mature and realistic. To be honest, I felt that Steve Rowland (the director’s son) presented one of the weak links in the film. Again, the part of Tom Jr was a pivotal one yet Rowland never felt convincing to me. As for the supporting players, Chill Wills pops up once again and gives a warm performance as the town preacher and one of Granger’s few allies. James Gregory was another of those familiar faces, a character actor many will recognize straight away, and he provided a nice foe for Granger. There’s also a semi-villainous role for Jacques Aubuchon as a crippled storekeeper with his eye on Fleming.

Gun Glory is available as a MOD disc from the Warner Archive in the US and there’s also a Warner/Impulso pressed disc from Spain. I have that Spanish release, and it presents the film very strongly. The transfer is anamorphic scope taken from a very clean and sharp print. I can’t say I was aware of any noticeable damage and the colors are well rendered. All told, there’s really nothing to complain about on that score. The disc offers no extra features whatsoever and subtitles are removable, despite the main menu suggesting that this is not the case. Anyway, we get a very attractive looking film with two good performances from the stars. The story itself is engaging enough, although there’s nothing on show that genre fans won’t have seen before. As I mentioned above, the direction is capable and professional without being particularly memorable. All told, this is a moderate western – interesting and entertaining but not exactly essential.