Films like Broken Arrow and Devil’s Doorway broke new ground for the western by offering up portrayals of Indians which were more three-dimensional than had traditionally been the case. Andre de Toth’s The Indian Fighter (1955) treads a similarly sympathetic path, showing the Sioux in a generally positive light. Few of the white characters are shown to be particularly admirable, even the nominal hero is not without his faults, succumbing easily to prejudice and greed. In addition, the film has a pro-ecology subtext that’s blended into the story in a way that’s refreshing and unobtrusive. This is not as powerful a film as the examples by Delmer Daves and Anthony Mann which I mentioned, yet it still manages to get its message across without resorting to the po-faced piety of more recent revisionist pieces.

Johnny Hawks (Kirk Douglas) is the Indian fighter of the title, an army scout recently returned to the west after the Civil War. He’s been sent along to guide a wagon train bound for Oregon through potentially hostile country. Before he ever reaches his posting though, he’s distracted by two events that are to shape the story that follows. The first is a sighting of Onahti (Elsa Martinelli), the beautiful daughter of Sioux chief Red Cloud, bathing naked in a river. The second is when he stumbles upon a botched deal between two white men, Todd and Chivington (Walter Matthau and Lon Chaney Jr), and a Sioux warrior exchanging whisky for gold. Both of these occurrences illustrate Hawks’ inherent sympathy for his old enemies. The former, naturally enough, arousing his romantic instincts, while the latter emphasises his willingness to side with the Sioux when confronted with the exploitative behaviour of his fellow whites. What draws Hawks to the Sioux is the respect he shares with them for the land which they occupy. Red Cloud’s principal objection to white men on his land is based on his belief that their greed for the gold it contains will wreak environmental havoc on the unspoiled paradise. Although Hawks doesn’t voice such fears specifically, there’s a telling moment later on when he confides in a photographer that the reason he doesn’t share his evangelical zeal to publicize the beauty of the frontier is his knowledge that attracting more settlers, and the trappings of civilization that they will inevitably bring in their wake, will spell the end of the west he loves. Even so, Hawks agrees to guide the wagon train through Sioux territory. However, the presence of Todd and Chivington among the settlers soon leads to trouble and puts the lives of everyone in jeopardy. While Hawks’ desire for Onahti drives him to neglect his duty, the equally strong desire of Todd and Chivington for the yellow metal sparks off a Sioux uprising. Faced with suspicion and hostility from both sides, Hawks is desperate to find some way of averting an impending massacre, and the terrible consequences it will have for the Sioux.

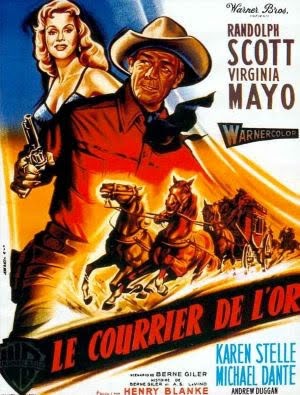

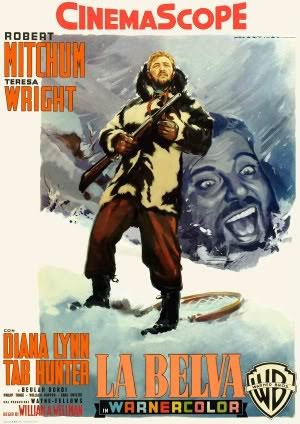

By the time he made The Indian Fighter, Andre de Toth had a string of westerns behind him (half a dozen starring Randolph Scott), and he’d developed into a highly competent genre director. He used the wide cinemascope lens to highlight the natural beauty of the Oregon landscapes where the picture was shot. These stunning images make it very easy to see why both Hawks and the Sioux want to do all in their power to preserve the land. The rich visuals are probably the biggest selling point for this picture, but de Toth was no slouch when it came to filming action scenes and his talent in this area is shown to great effect in the climactic Sioux attack on the besieged fort. Not only are the tactics employed innovative and surprising, but the way it’s shot gets across the excitement and danger too. Many of de Toth’s films display a matter of fact approach to physical violence and this one is no exception. Early on, we get to see two victims of Sioux justice strung up by the heels, though the camera mercifully avoids zooming in to focus on the exact nature of their demise. Then later, as the body of a cavalry officer is removed from the mount he’s been strapped to, his hat drops away to reveal the gory aftermath of his scalping.

The Indian Fighter came from Kirk Douglas’ own production company and, as was the case with Man Without a Star, he tends to overindulge himself a little. Generally though, Douglas manages to keep his vigor and enthusiasm within acceptable bounds this time. That is to say, he plays the role of Johnny Hawks with the level of energy that’s not unreasonable for the character. The outdoors nature of the shoot, and the degree of action involved, offered ample opportunity for him to show off his physical powers, which is just as well since Ben Hecht’s script never puts serious demands on his acting abilities. In the role of Onahti, Elsa Martinelli hasn’t a great deal to do beyond looking attractive, and she accomplishes that without too much effort; her introductory swimming scene is one of the more memorable openings for a western. Walter Matthau and Lon Chaney Jr are moderately effective as the heavies, the former faring best, but never pose any direct threat to the hero. The nature of this pair’s villainy comes from the repercussions of their actions rather than the actual menace they generate. Matthau is now best known for his comedic roles but he did make a handful of westerns at the beginning of his film career. He uses that calculating, scheming quality which came so naturally to him, and which he built up in subsequent years, to compensate for the absence of any real physical threat. Chaney’s career, on the other hand, was in decline by this time, and the truth is he cuts a rather shambling figure.

The Indian Fighter is widely available on DVD from MGM. I have the UK release, which I understand is a step up in terms of picture quality from the lacklustre US version. Although the disc offers nothing in terms of extra features, the image is quite pleasing. The anamorphic scope transfer is acceptably sharp, without noticeable damage, and represents the colours very nicely. A film that relies as heavily on its scenic views as this one does needs to look good, and I have no complaints about the presentation. Generally, this is a good and well-intentioned movie, although the villains are a little weak. Having said that, the action and the cinematography make up for such deficiencies. It’s interesting to note that with the exception of Douglas’ skittish lead and the thoughtful cavalry commander, the whites are portrayed as either grasping, prejudiced or duplicitous. The only truly honourable figures are the environmentally aware Sioux. which gives the movie a strangely contemporary feel. I liked it.