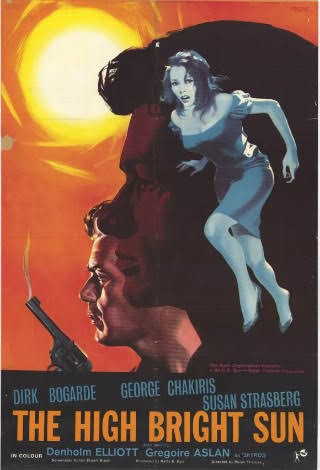

I’m not sure how many movies have been set during the guerilla campaign in Cyprus in the 1950s, but The High Bright Sun (1964) is the only one that I can recall seeing. It’s all too easy for a story which makes use of such a background to become bogged down in politics and thus dilute the drama. However, this film has the good sense to avoid becoming too mired in ideological matters and instead concentrates on telling a suspenseful yarn that could have been relocated to most any conflict zone without losing its edge. As such, we end up with a well paced thriller that builds tension relentlessly and holds the attention right to the end.

The tale is all about finding oneself in the wrong place at the wrong time. Juno Kozani (Susan Strasberg) is a Cypriot-American student visiting the island where her father was born and staying with some old family friends. Having witnessed the aftermath of the fatal ambush of two British soldiers by EOKA guerillas, she is interviewed by an intelligence officer, Major McGuire (Dirk Bogarde). Although Juno can only tell him the few mumbled words of a mortally wounded sergeant, McGuire’s suspicions are aroused. He’s one of those jaded colonial campaigners who has grown accustomed to the guarded silence of the locals, and routinely takes it for granted that details will be withheld. In this case though, Juno has told him all she knows, but he has a hunch that the guerilla leader, Skyros (Gregoire Aslan), was involved. What both he and Juno are unaware of at this stage, however, is that her host is using his flawless respectability to cloak his involvement with the paramilitaries. Following a vaguely unpleasant dinner party attended by a family acquaintance, Haghios (George Chakiris), Juno blunders into the library and sees too much for her own good – a secret visit by Skyros. This is the point at which the story really shifts into gear, with Juno having inadvertently placed herself in a very dicey position. She now has to do her utmost to convince her hosts – and in particular, the hostile and dangerous Haghios – that she didn’t notice anything untoward. In the meantime, McGuire is playing his hunch that Juno knows more than she can or is willing to say. By the by, it’s decided that Juno represents too great a threat and she finds herself the quarry of the seemingly unstoppable Haghios, first in a hunt across the beautiful countryside, and later holed up and under siege in McGuire’s apartment.

Director Ralph Thomas isn’t best known for his thrillers but he did dabble in the genre, including among his credits the excellent The Clouded Yellow and the unloved remake of The 39 Steps. The lion’s share of his work concentrated on comedies, but he plays down that aspect in The High Bright Sun, and succeeds in producing a tight thriller that draws you in as it goes along. The scene where Juno learns that what she thought was going to be a trip to the airport and safety is really a ploy to see her assassinated by the roadside is nicely shot. It also leads into the chase across the island where Thomas, and cameraman Ernest Steward, gets great value out of the stunning locations – Italy apparently standing in for Cyprus. The script, by Ian Stuart Black and Bryan Forbes, does contain some risible and admittedly clunky dialogue at a few points yet it also maintains its focus throughout and does its best to tell a story rather than descending into political diatribe. If anything it points out the dirty and indiscriminate nature of guerilla warfare, where the innocent often suffer the most at the hands of both combatants.

I thought all the actors turned in nicely measured performances, with Susan Strasberg doing fine as the girl caught out of her depth in a situation that’s spinning out of control. For the most part she underplays, and that’s fine as she’s supposed to be someone who must keep a careful check on her emotions lest she should betray herself. Dirk Bogarde wasn’t overly stretched in this one, though he does bring just the right degree of weary cynicism and self-effacing humour to his role. As the villain of the piece, the fanatical and homicidal Haghios, George Chakiris shows a surprising menace. He really did the coldly determined bit well, only the prospect of indulging in some physical violence bringing a gleam to his eye. There’s also a wonderful supporting part for Denholm Elliott as the apparently dissipated and alcoholic friend of McGuire who proves himself to be both ruthless and resourceful.

The High Bright Sun comes to DVD in the UK via Spirit, who have recently begun distributing a growing number of British titles from the ITV library. On the positive side, the film looks pretty good despite an apparent lack of restoration, without any major damage on view. The colour fares well and does justice to the location photography. The downside is that the movie opens with the credits letterboxed at about 1.66:1 before reverting to 1.33:1 for the remainder of the running time. I think we’re looking at an open matte transfer here, though it might be slightly zoomed too, judging from the extraneous headroom in some shots. This is by no means perfect, but it’s not a totally botched job either – a 1.66:1 movie doesn’t suffer as badly from a compromised aspect ratio as is the case with those composed for wider presentation. The disc is a very basic affair offering no subtitle options and no extra features. I found the film to be a well produced political thriller, with the emphasis on the thrills rather than the politics. It may not be an outstanding piece of work, yet the performances, scripting and direction are all professional and polished. Crucially for a thriller, it does deliver the necessary amount of suspense, tension and excitement. I’d call it a solid piece of entertainment that looks good and doesn’t outstay its welcome. I recommend giving it a chance – it’s certainly worth a look.

![£38]](https://livius1.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/02/c2a338.jpg?w=676)